Afrikaanderwijk Cooperative operates in South Rotterdam’s Feijenoord area. Evolved from an art project conducted in the area by the Freehouse Foundation, the Cooperative works on bringing together existing workspaces, entrepreneurs, producers, social organisations and the market. The Cooperative began its work by mapping the unrecognised skills and competences of residents in the Afrikaanderwijk neighbourhood, suffering from problems of low education, unemployment and a bad reputation. Based on these skills, the Cooperative created a number of organisations to help residents use their competences through establishing a neighbourhood kitchen and catering company, a textile workshop and a cleaning company, offering services on the market and bidding for municipal commissions, in order to keep revenues in the area and create jobs for locals.

“We allow individuals to pool resources and legitimise their informal businesses”

What is the origin of the cooperative?

We started with the Freehouse Foundation, initiated by visual artist Jeanne Van Heeswijk. We became really active in 2008, in the Afrikaanderwijk neighbourhood within the Feijenoord district of South Rotterdam, an area with many problems: unemployment, many people dependent on social benefits. But there are also a lot of values, many young people, skills, craftsmanship and creativity. We wanted to see if we can make use of those values by regenerating the area from within, together with the people living there. Also, many areas around the neighbourhood were undergoing urban renewal but not Afrikaanderwijk: we wanted the area to benefit from all this surrounding development instead of being left out. Our research question was: How to revitalise the area in such a way that local inhabitants and entrepreneurs will not be displaced?

Where did you start?

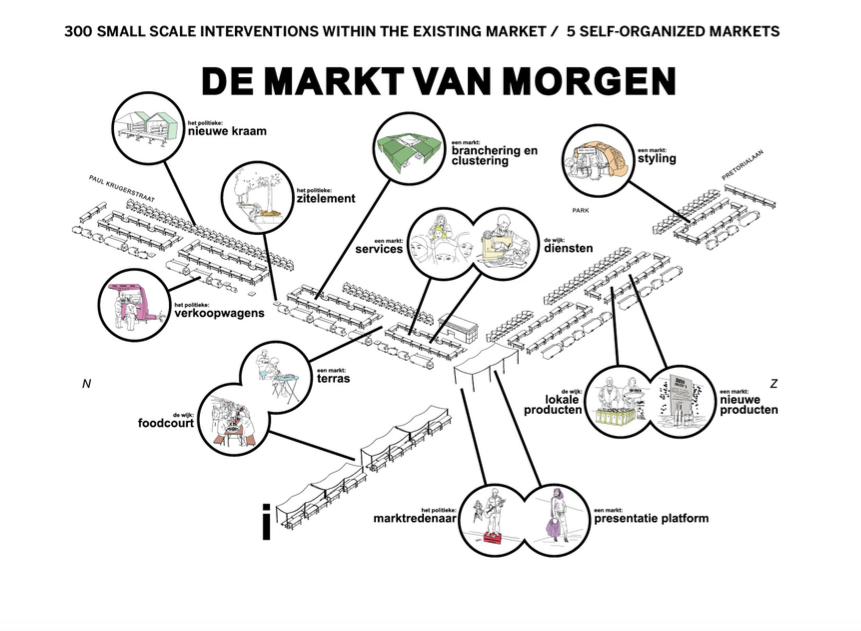

We started a series of project around the questions of production and public space. Our first focus was the local market, held twice a week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. We expected that it could be an added value to the area, attracting people also from the outside to taste local culinary products. The market has a big potential, with its 300 stalls and 15.000 visitors. But it also had a lot of problems: there was little diversity among the stalls. Of the 300 stalls, around 100 were selling food and vegetables, and there were lot of empty stalls. Sellers were making little profits because it didn’t attract enough people: 15.000 sounds much, but many of these people from the area didn’t have much to spend. And the market’s image was not attractive enough for the neighbouring areas.

How did you intervene?

We thought this market, because the area is very rich in cultural diversity, could be represented in a way to make it as attractive as markets in other countries. We called our initiative “De Markt van Morgen” (tomorrow’s market) and we aimed at creating an image of what we saw this market could look like in the future. We organised a live 1:1 maquette of how this market could look, feel better and work better. We created 300 small scale interventions within the existing market, and we also organised five markets ourselves. The interventions were based on a match between an artist or designer and a market seller: their form could vary from the restyling of a stand to making prototypes of new market stalls, prototypes of new products. The market sellers didn’t have the to present their valuable goods, and designers could really add something to that. We also introduced new typologies for the market because a market is more than just a place where you buy goods. It’s also a place where you exchange ideas and where you experience things. If you look at the classical agora, it was a place where people met each other and we wanted to bring that back to the market today. So we organised some entertainment, music and theatre events, fashion shows, and all kinds of activities to make people surprised when they visit the Afrikaanderwijk Market, hoping they would stay longer, buy more and want to keep coming back.

What emerged from your interventions?

We found out that a lot of our interventions were beneficent in our eyes but were in fact forbidden, prohibited within the existing legislation. So we started to call these interventions acts of civil disobedience. For instance, just singing at the market is not allowed, because you would attract more than three people and you’re not allowed to form a crowd at the market (there’s a ban on assembly). There are very strange regulations like that, but because we were doing all this in an art context, we could deal with them flexibly. They even strengthened the outcome of our project since they stressed an urgency. But if you’re a real market seller, then all these legislations really limit you in your entrepreneurship and also prevent the market from flourishing. For example, when we made orange juice from ripe orange, this was not allowed because we had a permit to just sell fruits but not drinks. All these obstacles we came across were incorporated into our project. And the end, we made a new layout for the market, in which many of these limitations were undermined: for instance, if you create a “presentation space” where you present products, you no longer have a legal problem with creating a crowd. Also, it was not allowed to have a terrace in front of your stall because then the fire department couldn’t pass: therefore we created a food court with the fire department.

What was the impact of these changes on the neighbourhood?

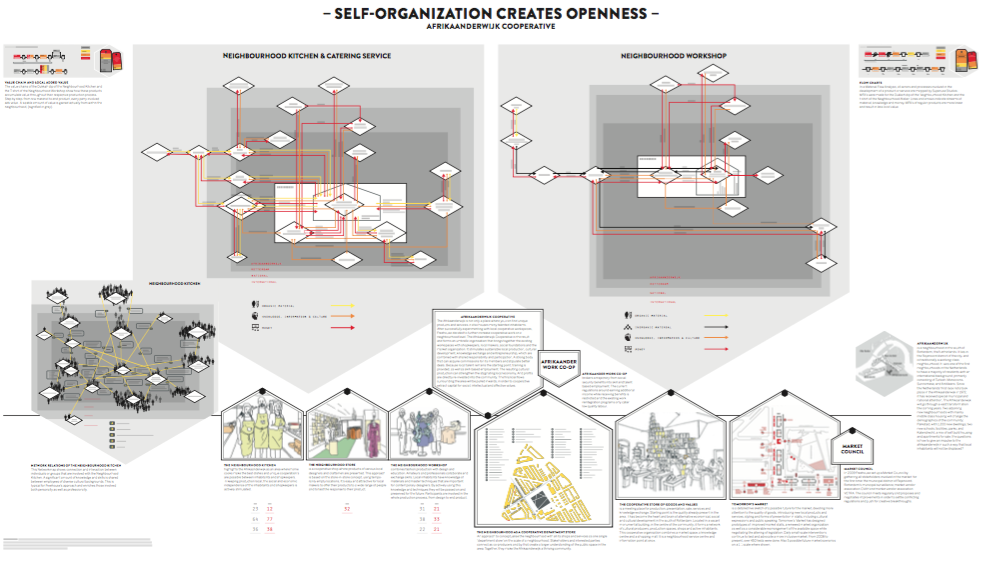

After the we started with the market we began to zoom out into the wider area. We came across a lot of people who were part of strong informal networks. Many people were working in food production, but they couldn’t really sell or earn money with their skills because they didn’t have professional kitchens. There was an empty kitchen in the neighbourhood so we created access for these home cooks to the kitchen so that they could start organising a catering service together. We have now twelve different nationalities in the Neighbourhood Kitchen and they run a catering business together; we started out with an art funding for two years and for three years now the kitchen is independent from funding. Working together in this cooperative kitchen made it easier for people to use their skills and earn money.

Besides the kitchen, we have another cooperative space for textile production that works the same way, creates room for people to meet, and gets people involved into what is going on in the area, contributing to the local economy. There are many people here with specific skills and talents in knitting, embroidery or stitching that designers can benefit from. Therefore we bring them together in the sewing studio that works for fashion designers and other commissions: for example, we made a corset for Jean-Paul Gaultier. This made everyone very proud: while this neighbourhood is often seen with a negative optic, a designer like Jean-Paul Gaultier just looks at the products that come from here and the craftsmanship of these women without this negative sentiment. We see the whole neighbourhood as one big department store, so we work with all the local shopkeepers that can be a part of this. Just like we did at the market, we try to match these shopkeepers with designers and artists to work on a better presentation of the area as a shopping area. We organise a lot of events in the neighbourhood to attract people from the outside and connect them with the local networks we have. Our central location is a neighbourhood common called het Gemaal op Zuid: it is a former water pumping station that is now transformed into a public place for the neighbourhood, where meeting, presentation and production comes together.

How did you formalise your work in the neighbourhood?

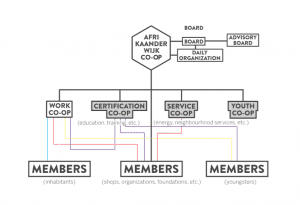

Although we started out as a non-profit artist initiative but we found out that this form didn’t really suit anymore the activities that we were doing and because we had good experience with the cooperative model, which we used in the cooperative workspaces, we decided to create a cooperative at the scale of the neighbourhood. In 2013, we set up the Afrikaanderwijk Cooperative, an umbrella organisation, and handed over all our activities and the cooperative work spaces to the cooperative. The goal of this neighbourhood cooperative is to stimulate sustainable local production and entrepreneurship, by developing local skills and setting up chains of collective production. We aim at producing economic opportunities, leveraging political power to shift policy, and negotiating economic advantages by reinvesting profits in the area: to look at all the money that is going around in the city and see if we can change the flows of money and channel it towards the people in the area. While it’s often seen as a poor and deprived area, there is a lot of work done and a lot of money spent here: it doesn’t stay here but is brought out of the area by bigger companies that work here. We want to lock this money in the neighbourhood, by creating local jobs. With Freehouse, we are now part of this cooperative, as one of the members together with many shopkeepers, inhabitants and the cooperative workspaces we initiated. There are several “sub coops,” we have a board and a daily organisation. The cooperative allows individuals to pool resources and legitimise their informal businesses. For instance, we created an energy collective that made it possible to buy energy collectively, realising substantial savings for businesses in the neighbourhood and also looking into the possibility of helping households with our collective buying power.

[flex_gallery id=”9616″]

What is the economic model behind the cooperative?

With the cooperative, we don’t just focus on culture production anymore but also start up new businesses. We started a cleaning company called SCHOON that ensures that cleaning work that normally is outsourced to companies elsewhere is “insourced” and carried out by members of the Afrikaanderwijk Workers Co-op. Now people living in the area clean 80% of the buildings owned by the area’s main housing agency. Similarly, with the Neighbourhood Kitchen, we set up Home Cooks Feijenoord, a meal service for elderly, sick, and disabled people where professionals and volunteers prepare meals in people’s homes. We also rent out the Gemaal op Zuid to commercial, governmental and private parties that allows us financially to share the space with locally based co-op members and inhabitants, as a space for presentations, exhibitions, meetings, dinners, workshops, knowledge exchange and so on. From all these different flows of money, our revenue, 50% goes to our members, 25% goes back to the cooperative and 25% goes into fund for social and cultural projects. At least twice a year, we organise a general assembly for the cooperative, and there we decide what to do with this fund: what processes we want to initiate, and what projects do we want to put on the map. We can also spend the money from thus fund on events: this can be a music event or cultural promotion for the neighbourhood as a shopping area.

How do you cooperate with local governments, institutions and policies?

What we are doing is we challenge the government and local organisations to spend their money locally. Instead of hiring services from outside of the neighbourhood, we look inside the neighbourhood and ask the cooperative if it can fulfil a job, that way creating new jobs that were not local before. I think the big issue is gaining trust of governments and organisations… that not because that you are local that you don’t have knowledge. It’s not because you are local that you are not able to work in the network. By spending it locally you have a bigger range of benefits than only the job.

For instance, we now work together with the municipality on a pilot program for the cleaning of the market, because the market is a big mess maker and by cleaning it with local people it creates many jobs. We won’t be able to do that for less money but people who are doing that know the market sellers, know the people in the neighbourhood, it’s a bigger responsibility that you are creating because nobody will spit in their own house, or throw trash in their own garden. We are organising it differently and we expect that we can create a cleaner market than the way they are organising it now. It goes further than only the market, it goes through the whole neighbourhood, the cooperative creates jobs, we strengthen the local economy.

This sums up what we are, what a neighbourhood cooperative can be. We focus on the skills of the neighbourhood and to work as an economic, social and cultural engine. We know that in order to lock money flows in the neighbourhood, you don’t really have to scale up but strengthen local networks and connect them to networks outside the area. We can make a stronger city without losing people. We can be inclusive: small scale organising at the neighbourhood level is the future.

Interview with Annet van Otterloo on 05.05.2016 during the Funding the Cooperative City Rome workshop