Living and working in times of physical distancing and – sometimes forced – digitalisation cannot always be about video meetings via Zoom, Skype or other similar platforms. Or at least, we should not limit ourselves to these kinds of interactions. The Eutropian team, as many other researchers and practitioners in the field of urban studies, is constantly involved in video conferences to carry on new and ongoing projects but now, facing ongoing lockdown, we want to make digital interaction more engaging and fun. Inspired by the success of gamification in the field of urban planning we started exploring existing games and digital platforms to give a twist to our work.

by Jorge Mosquera & Giovanni Pagano for cooperativecity.org

“We don’t stop playing because we grow old; we grow old because we stop playing”

George Bernard Shaw

The need of a twist in participatory planning processes

How do urban practitioners deal with the issues resulting from the global pandemic, social distancing and the inability to travel, in their activities?

Participatory planning refers to integrating citizens’ observations, concerns and aspirations from the start and letting all participants find solutions collectively that meet the community’s true needs. More than just a simple consultation, experts and professionals can promote an open dialogue and interaction between citizens and then supplement their plan with the information provided by the participants. However, since the pandemic turned the world upside down and the shelter-in-place order was issued globally, it is necessary to find ways to advance participatory planning practices under unprecedented circumstances. In order not to let the public safety restrictions curb the participatory process, community outreach and public engagement have shown the need for innovation.

The introduction of digital and mobile technologies has profoundly changed everyday life, transforming the way people communicate and interact with one another, but also the way of consuming or producing services and experiencing places. In this regard, two relatively new ways of citizen engagement have gained popularity: participatory e-planning and gamification practices. Participatory e-planning refers to the technology-mediated interaction between the civil society sphere and the formal politics sphere (Saad-Sulonen, 2012). Gamification practices concern the mobilisation and implementation of ludic elements in order to manage “real” issues and affect human behaviour (Vanolo, 2018).

Given the emerging new needs towards these practices, this article, in the first instance, presents research carried out by Eutropian on existing gamification and various digital participation practices. Subsequently, insightful experiences by four urban practitioners dealing with the actual restrictions were also shared in a Cooperative City Dialogue webinars entitled “Digital Games to Experience and Design your City”. In conclusion, recommendations and a first game experimentation enabling a more playful digital participation, developed by Eutropian, are presented.

Gamification and digital engagement practices in spatial planning and urban design

Gamification implies the use of specific forms of nudging based on ludic elements. Vanolo (2018) identifies nudging practices in gaming mostly connected to the provision of rewards, which encourage behaviours and decisions that are supposed to be beneficial for society and for individuals, e.g. acting in sustainable and healthy ways. In addition to that, Lerner (2014) notes that well-designed games may encourage democratic processes because they invite participation, require decision-making, foster compromise, and encourage people to cooperate. Additionally, playing usually does not require specific knowledge, allowing a greater variety of participants. Accordingly, literature shows that gamification and digital engagement practices are widely used in spatial planning and urban design for various reasons.

In the first instance, elements of games, based on digital technologies, have been implemented in cities in order to allow new and stimulating experiences of the urban space. In this regard, W_NDER: A Game for Times of Social Distancing is a clear example. It is a two-player game designed for two participants who are curious to explore their urban surroundings while walking 15-meters apart and talking on the phone. One player is the Wanderer and the other in the Wonderer. The Wanderer sets the direction and answers the questions that the Wonderer asks openly and honestly. In turn the Wonderer interjects with questions and actions to the other player. This experience makes it possible for people to discover their surroundings with a different perspective and in a playful way.

Additionally, literature reveals that various non-ludic apps – as their mechanics appear to be playful -have been considered as games over time. These can also help to collect data on people’s behaviour. GreenApes and Stadtsache are two clear examples of apps that collect data on sustainable behaviours and about people’s opinions. Greenapes is a digital platform rewarding sustainable actions and ideas. Cities can choose the behaviours they would like to reward (green mobility, waste sorting, energy savings, participation and volunteering). By doing and sharing their action, citizens’ will get prizes and at the same time inspire others. Stadsache is also a digital app, focused on children. It is an innovative tool for collecting photos, sounds, videos or recording paths. The app gives specific tasks and actions and the result is shared with other users of the app. The collected experiences and materials will gradually create a map that makes children and young people visible as city experts. These experiences, also, provide data to authorities and urban practitioners about citizens’ sustainable behaviours and perceptions, especially from youngsters, of the urban living environments.

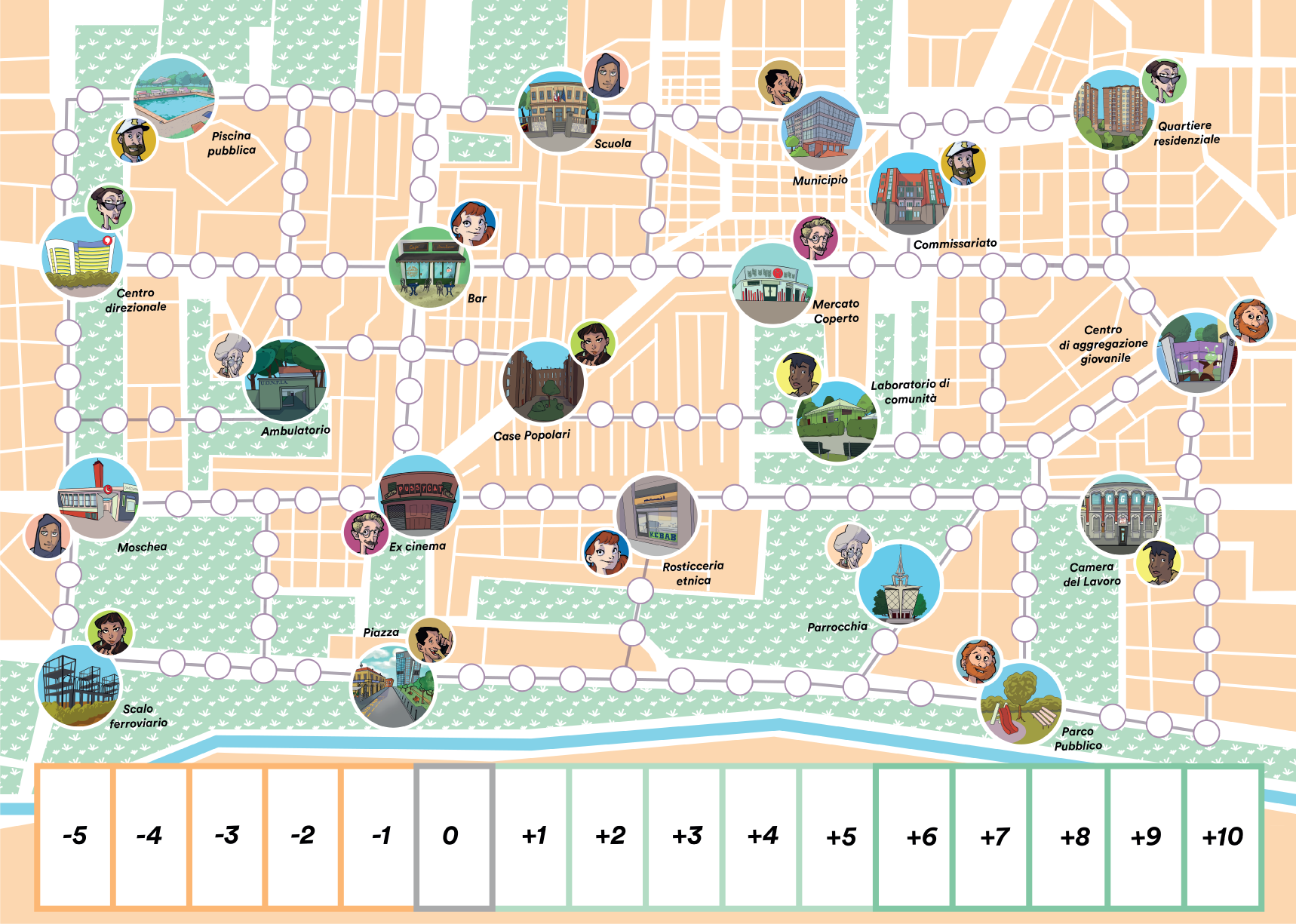

Lastly, more ‘serious games’ that also include educational goals, could empower citizens by making real-life decisions and together imagine a more liveable city, instead of being exclusively for recreation. Literature affirms that early application of serious games in urban planning have addressed topics such as land use, transportation, ecology, and management of natural resources (Ampatzidou et al., 2018). In this matter, Dynamoscopio, an Italian interdisciplinary agency of research and design in the field of urban regeneration and social innovation, developed Gametrification – the game of urban regeneration. The board game, which presents a map with significant places and spaces of a neighbourhood, is not only a play space, but a “square”, a place of meeting and comparison between different values. The actions performed in the game modify the space and condition the equilibrium of the neighbourhood, making experience of its precariousness. Each transformation, in fact, always corresponds to a reaction of several characters who will be more or less satisfied, more or less interested by the change. It generates awareness and debate regarding transformations, disseminates information and stimulates the collective imagination regarding the future of the neighbourhood.

These are only some ‘best practices’ operating in the field that show how participation and citizens’ engagement is possible and, perhaps, even more powerful if conducted in a playful way. We have also highlighted the increasing number of solutions that encourage participation through technologies and digital apps. However, ‘serious games’ used to create debate about real-life situations are largely affected by the current situation and all the safety restrictions that are in place. There is a need to be readapted. Something as simple as a Miro board can become a formidable platform for co-design.

Sharing the outcomes of Cooperative City Dialogue: “Digital Games to Experience and Design your City”

“Digital Games to Experience and Design your City”, a Cooperative City Dialogue webinar, brought together four international teams of facilitators working on gamification. Moving from a local context to the sphere of European city networks, our guest speakers shared with us their experiences and observations in regards of engagement and adaptability to new Covid-19 restrictions.

Local development and liveable communities

Seeking playful places in Budapest, the “Mind the Game” project initiated by Mindspace in 2014 started by asking citizens “How do we playfully motivate city dwellers to make their city more liveable? What will make a city more liveable, lovable, colourful, where residents form a community?” Mindspace, an organisation that works on participatory processes and social inclusion, sought answers to these questions through a series of conferences and an urban game. Szilvia Zsargó shared with us some of the activities/games developed in this process such as a dancing session for strangers to meet in public space, riddles to solve in the middle of the street to know more about a district’s history or even an outdoor backgammon session (inspired by the local tradition of playing chess at spas).

Szilvia believes that games need to be purpose-driven in order to keep people motivated to participate. It is easy to get someone’s attention for a few seconds but to keep it for an entire gaming session demands a precise set of skills, “It’s a matter of fun and action, mediation, and organisation”. Moreover, she highlighted the costs of online activities as they entail a bigger effort for mediators.

On a different scale, and facing the efforts of online activities, Joao Martins & Gonçalo Folgado from Locals Approach shared with us their work on the “Manual for Local Development” in Lisbon.

The Municipality of Lisbon has been supporting participation and grassroots initiatives, focusing on fighting poverty in priority intervention neighbourhoods through its BIP/ZIP programme for more than ten years now. A remarkable work producing a big amount of data, some of the programme’s rules and principles needed to have a translation to a more accessible and engaging language. The special synergy developed between the Municipality, projects funded by the BIP/ZIP programme and the team of Locals Approach led to the creation of the Fórum Urbano where all the data once collected by the Municipality in a technical and bureaucratic language has been transferred into an interactive platform.

Translating technical documents to a platform, and subsequently to a manual, Locals Approach created a series of cards explaining all the different activities developed in time by the BIP/ZIP programme. These cards can be read as a manual for local development but can also be played for a better understanding of projects and for a better co-creation of new ones. This Manual for Local Development has been conceived for real-life workshops accessible to every citizen but has been recently adapted for an online board game on Miro. A first online international workshop has been realised for the URBACT Transfer Network Com.Unity.Lab led by the City of Lisbon. In this workshop, through different rounds, players chose and discarded cards in order to design together a project able to reach an assigned goal placed at the centre of the board. At the end of the game, the co-designed project was pitched.

During such activities, “It is interesting to see the debate and the level of participation of the players” recalls Goncalo Folgado – every move must be justified, explained and shared with and by all players in order to move on. While the Forum Urbano platform represents a bridge between the administration and citizens to access data about local projects, the Manual for Local Development shows the importance of adapting a new language – when sharing the story of a local project – and engaging players in a serious exercise of democracy in a safe(r) game environment.

Amplifying democracy through gamification and playful cities

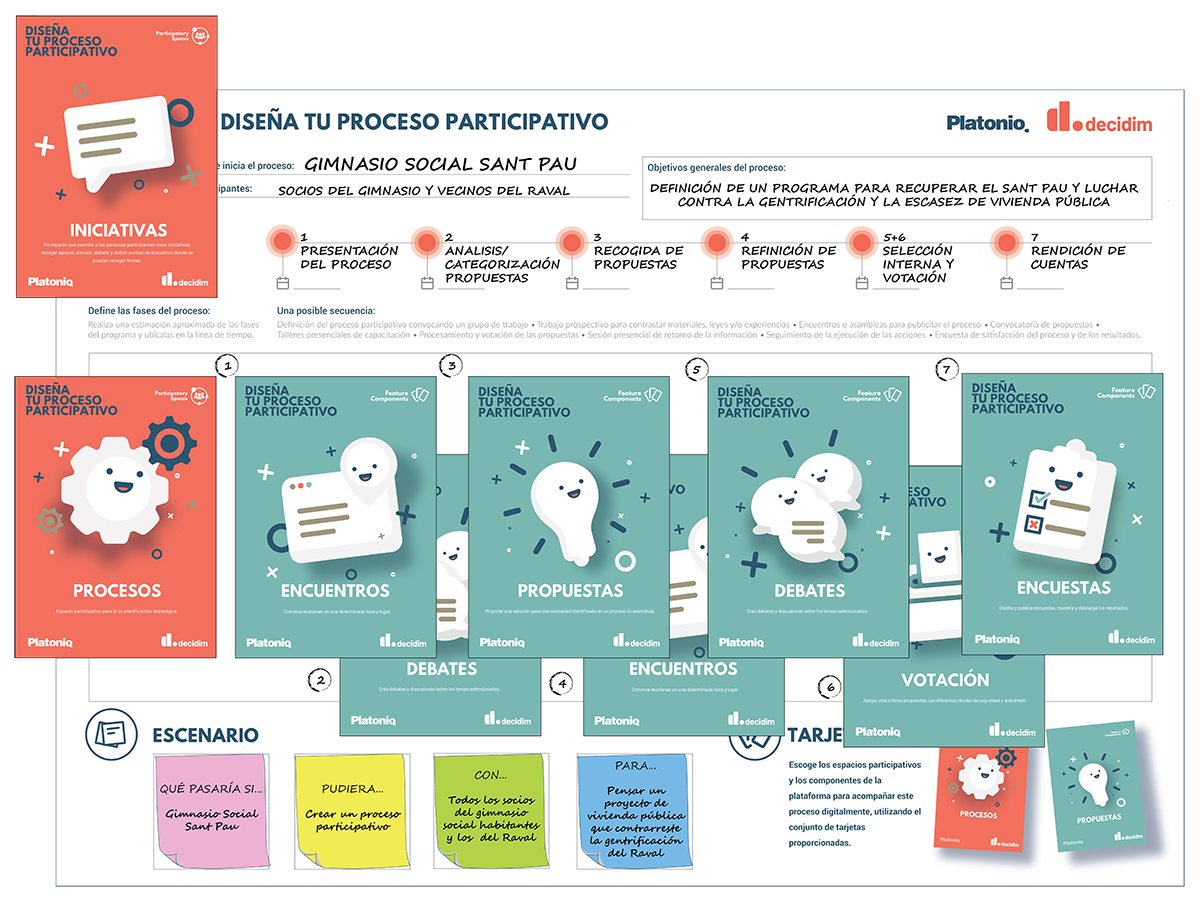

By aiming to prove that “Democracy is fun… if you take it seriously”, the creativity and democracy organisation Platoniq has been working on digital transition and co-creation methodologies for years, focusing on participation with gamification and digital tools – their games database is available at https://wotify.eu/. We had the opportunity to hear about Platoniq’s work from its co-founder Olivier Schulbaum.

For Olivier and Platoniq, games are a way to create engagement in times when democracy can be seen as in bad shape. “74% of people in Spain feel unsatisfied with the functioning of democracy and two out of three people from marginalised neighbourhoods in Spain do not vote”, explains Olivier. For this reason, “Decidim the Game” brings to real life Barcelona’s participation platform Decidim, a digital infrastructure built entirely and collaboratively as free software to empower “free open source participatory democracy” (the claim of the project) for cities and for every kind of democratic organisation. Pursuing this goal, Platoniq’s work has been to better communicate the work structure of Decidim bringing it to the more engaging and fun world of boardgames. Developed on Platoniq’s in-house classic methodology, the “What-if-I” tool, the game calls participants to design their own participatory processes thinking of: (I) WHAT IF AS … type of user; (II) I COULD … specific action; (III) WITH … tools/contents/features from the Decidim platform; (IV) SO … main goal / benefit. The game’s most relevant features are the Participatory Spaces & Feature Components cards for designing participatory processes as they are based on real Decidim modules. Therefore, this game brings to a broader audience the functioning of the open source platform and invites everyone to think strategically, according to specific goals and precise tools to be used, as if to make the construction of a participatory process both scientific and fun.

Another contribution of Platoniq’s to the sphere of digital democracy is the Dashboard of Citizen Proposals‘ for Decide_Madrid, (Decidim’s sister project), that helps citizens in the mission to get Madrid’s 1% of the census (22,000 citizens) signing their initiative to make it go to referendum. To facilitate this task, Platoniq has been designing a more progressive engagement strategy based on a gamified lifecycle: once thresholds are reached in terms of the number of supports (nudge), initiators can unlock a series of resources (reward), such as: a communication kit on paper, a communication kit on social networks, or even a day of visibility on the Landing page of Decide Madrid, or on the City Council’s social networks.

Our hope is that similar projects could prove to urban governments and decision-makers the importance of taking advantage of the digital transition. Worth mentioning here is the particular context in which Platoniq and Decidim are working: the city of Barcelona, a city whose ambition is to lead European social and technological innovation with policies dedicated to participation, commons, and open data. This demonstrates the importance of municipal programs enhancing both participation and innovation of citizens.

The previous projects about innovative practices in participation confirm the need for democracy to be fun. 20 years ago already, the City of Udine adopted playfulness as a philosophy for civic engagement in urban development. A public policy initiated with a mobile toy library, a Ludobus for summertime activities in the city centre and in suburbs, led to the creation of an “office of play” established to promote a permanent education on playfulness for schools and other institutions. URBACT has seen the potential of this policy in terms of inclusiveness (of all citizens from children to elderly, migrant, and vulnerable people) and recognised the City of Udine as a good practice able to lead other cities implementing the same philosophy. Klaipėda (Lithuania), Larissa (Greece), Katowice (Poland), Cork (Ireland), Esplugues de Llobregat (Spain), Novigrad-Cittanova (Croatia), and Viana do Castelo (Portugal) are the cities joining Udine in the URBACT Transfer Network Playful Paradigm. Each city will work on playfulness to face their specific challenges e.g. Klaipeda is promoting children’s healthy lifestyles; Esplugues de Llobregat is raising environmental awareness; Larissa promotes integration and social cohesion and Cork is using playfulness as a tool for placemaking.

Ileana Toscano, hosted in the Cooperative City Dialogue as Lead Expert of Playful Paradigm, highlighted the importance of having playful places within cities to make people play freely, and not bound to specific consultation or design projects. In this sense, “playfulness” differs from “gamification” as a more free philosophy, claiming that play can just be for fun.

Takeaways for playful digital participation

Based on our detour into innovative gamification practices we have identified a series of guidelines to enhance participation in a period of physical distancing taking into account the challenges of adaptation and moderation in such a new scenario. Currently, there is a great variety of different online collaborative platforms that can be used as tools for brainstorming and playing together while involved in an online video call. Tools like Miro, Mural, and Conceptboard allow a great creativity and playfulness starting from boards or cards that one can upload onto the digital workspace, inventing new games.

It is important to highlight here that, despite the increasing amount of digital tools, it is not always easy to organise enjoyable and engaging gaming sessions. A whole new kind of challenge arises in the gamification process. As stated by our webinar guest Gonçalo Folgado: “The game can be the most interesting thing in the world but you will always risk people being fed up by the activities – there’s the need for a thrill!” Moreover, we need to consider the time factor: people nowadays cannot spend so much time in participatory processes or (extra) online activities – “therefore it is important to create straight to the point questions and tasks when creating digital activities and collect all the data generated” suggested Olivier Schulbaum. Hence comes the challenge, as a facilitator, to be even more active and accurate when interacting with participants as it is evident that to replicate the full excitement of real life activities is a hard task. Accordingly, we have constructed a series of guidelines that suggest how to create and develop a playful digital participation process.

Digital participation guidelines

- The first principle we have identified is to create a clear objective that can get participants’ attention and interest. General topics such as “how to create a resilient community to face climate change” or “how to shape social inclusion of vulnerable people” – as in the case of the Lisbon’s Manual for Local Development – can constitute a good start to define an objective. Nevertheless, a further definition of a game’s objective must include beneficiaries, scale of action and other specific features.

- Secondly, we acknowledged that putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes boosts the engagement of the participants and opens up the discussion. This could be facilitated by the creation of different characters, with a short storyline, which participants could pick in accordance to their preference. Moreover, participants are advised to choose characters which are the most distant from their usual role in real life. Even though this role reversal could be challenging, it will bring a unique perspective to the participatory process and increase the participants’ engagement.

- Thirdly, in regard to the time that people invest in the participatory process, the different phases of the game should be understandable and straightforward, but also, engaging. In this regard, it is important to create a digital board game divided in different sections for each phase of the game, which guides the players through the process. Moreover, the achievement of a goal for each phase of the game gives greater satisfaction to the participant, and therefore it encourages him to complete the session.

- Additionally, a classic way to keep the attention high is to plan for rewards and bonus features when players achieve a partial result. Everyone can relate to this feeling when playing video games and unlocking resources, extra lives or bonus skills for an avatar. This can be also realised in a real and serious way, when participatory processes are split up in different levels.

- The facilitator’s role in digital activities is crucial. Engaging the participants in the participatory/gaming session, and facilitating the progress is a hard job, though facilitators are trained to do it. In this sense, giving the word to different players, sharing the screen occasionally, or moving momentarily and in an easy way to a different platform could be stimulating enough to keep attention high. However, the importance of communication skills in speaking, empathising and gaining the sympathy of participants should not be overlooked. In relation to engaging and facilitating, we find the importance to create safe spaces of participation where people can feel free to express themselves as part of the game prerequisites.

- Lastly, we suggest having a final moment in which participants can share their results and personal feelings of the process. This can be the moment to open a discussion about the final outcome. Additionally, developers could also take advantage of this moment by asking reflection on the course of the process to further improve the digital participatory process.

Digital facilitation in action: Eutropian’s new board game

Our work has already led us to apply these guidelines to facilitate communication and co-design within our European projects.

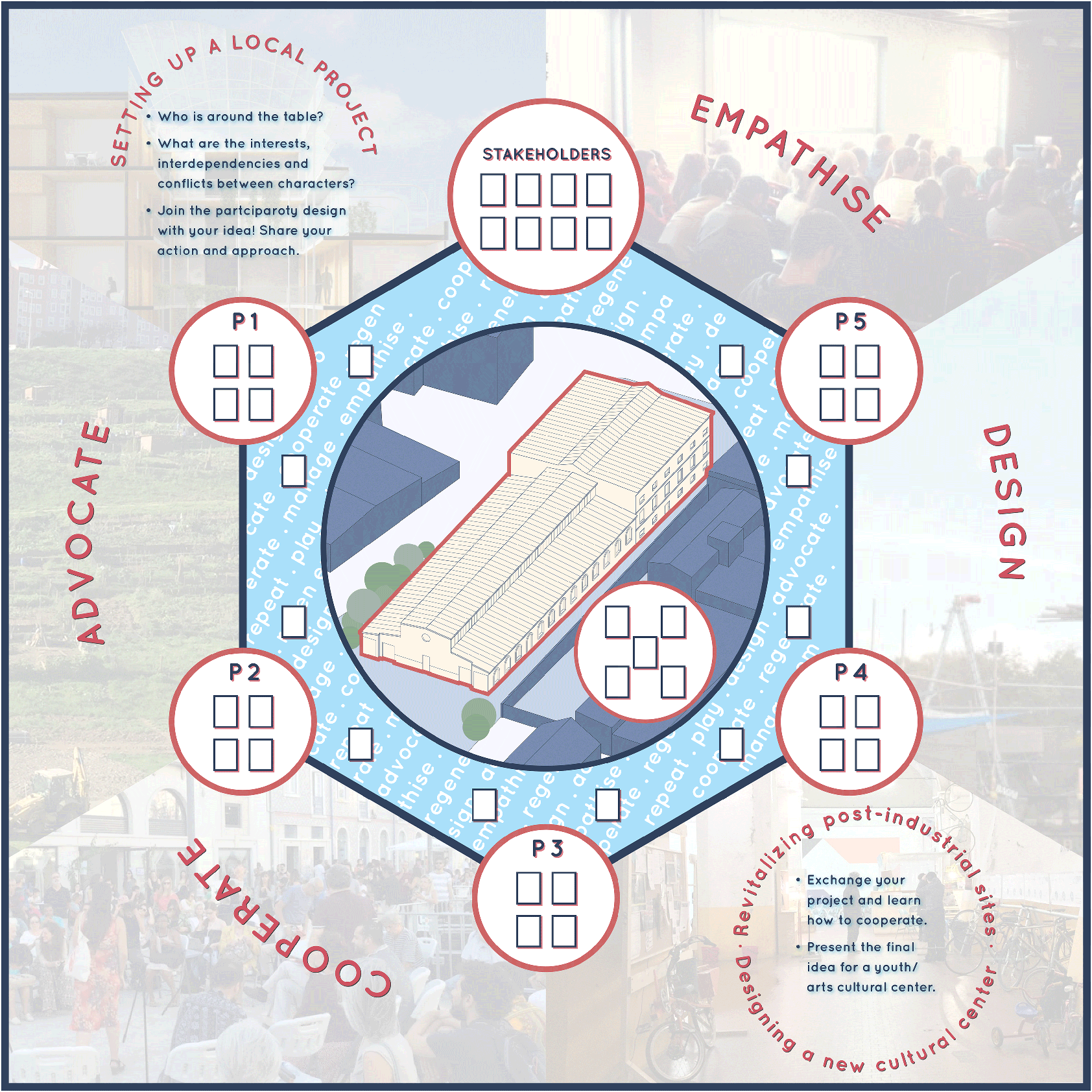

A first experience of this new way of working online was tested within the project “Commons in practice” carried out in partnership with the city of Durrës in Albania. For this project, Eutropian developed a customised virtual board game in which local stakeholders as well as participants from Eutropian took part. The objective of the game was inspired by the existing opportunities to develop common spaces in Durrës: to transform a fictitious empty factory building into a community space through stakeholders participation. Miro was chosen as the platform to host the board game and provide interactivity.

What steps did the game follow?

In a four-step co-design session, participants were called to: (1) empathise with the chosen stakeholder card representing a different kind of character involved in the urban regeneration process; (2) design their personal project for the urban void playing only two of the four cards they have been provided, one functional and one methodological card for their regeneration project; (3) co-design a hypothetical solution through a common discussion of all the cards previously selected – as a result, only five cards are selected to reach the main objective; (4) share the final co-designed project in front of other players and/or a broader audience to evaluate its coherence and effectiveness.

References

Saad-Sulonen, Joanna. (2012). The Role of the Creation and Sharing of Digital Media Content in Participatory E-Planning. International Journal of e-Planning Research (IJEPR). 1, 1-22. 10.4018/ijepr.2012040101.

Vanolo, A. (2018). Cities and the politics of gamification. Cities, 74, 320-326. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.12.021

Lerner, J. A. (2014). Making democracy fun: How game design can empower citizens and transform politics. MIT Press.

Ampatzidou, Cristina & Gugerell, Katharina & Constantinescu, Teodora & Devisch, Oswald & Jauschneg, Martina & Berger, Martin. (2018). All Work and No Play? Facilitating Serious Games and Gamified Applications in Participatory Urban Planning and Governance. Urban Planning, 3 34-46. 10.17645/up.v3i1.1261.