In the early 2000s, some cities in the Central Eastern European region began to introduce new mechanisms for citizen participation in urban development. These attempts have remained mostly sporadic however, and the possibilities of the third sector in shaping the region’s cities have remained very limited. In order to understand the reasons that hinder the evolution of a resilient network of civic actors and supporting financial structures in the region’s cities, we have to understand the limitations of the socio-cultural and economic context in which they unfold. In this text, Hanna Szemző describes the background that conditions the impact of civic and social economic initiatives on urban development processes in Central and Eastern Europe, with particular attention to cooperative housing and the reuse of abandoned spaces.

By Hanna Szemző

This article is an excerpt from the book Funding the Cooperative City: Community Finance and the Economy of Civic Spaces

With the notion of the creative and sharing economy gaining ground, and the concept of the creative city evolving into the smart city, much attention has been paid to the economic aspects of new city development and the role of third sector economies as part of it. These economies encompass a variety of not-for-profit originations that often have social and political roles, alongside their economic ones. Organisations active in civic or third sector economies often operate as agents filling in the gaps left by welfare states, offering the possibility of a bottom-up, more inclusive/innovative growth. In urban areas specifically, third sector organisations can contribute to the provision of services for marginalised groups, to the supply of alternative housing solutions, to the rehabilitation of neglected neighbourhoods or to the introduction of new, innovative ways of development and the re-use of abandoned areas in cities.

A slow-paced emergence of the third sector in the cities of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries has recently opened up opportunities for new developments. Urban development in this region has often been trapped by the occasional cumulative barriers of an overwhelming reliance on public funding (many times characterised by haphazard and non-consequential funding policies), the short-sightedness of municipalities under the strong influence of the local political elite (and their political and economic dependence on local relations) and a short term profit-maximising attitude of an overwhelming share of private investors. Adding to this, there is what can be described as the path dependence regarding bottom up initiatives, where the socialist heritage of lacking civil society and civic initiatives has diminished relatively slowly, a characteristic still partially tangible a quarter of a century after the regime change. And finally, the phenomenon of state capture created a situation in some of the countries, where private and public stakes have become hard to distinguish, resulting in the domination of particular interests over larger public investments.

All these components contribute to the fact that developing the cooperative city in the Central European context is a process more locked into daily political arenas and rigid governance structures, than in Western or Northern Europe. But paying special attention to this region showcases how the existing governance practices, a strong top-down administrative decision-making structure (although the level varies substantially between countries) can live together with third sector organisations that would require more flexibility and openness to really flourish and maximise their effect on the cityscape and city use. The article argues – through examining how the use of public (civic) space is defined and how local administrations relate to these uses – that despite their growing presence, many third sector organisations are still tied up in a contest with municipalities, who generally fail to support the movements that transform the cityscape and its governing structure. As a consequence, in the region, those interventions can flourish where the dependence on public investment becomes minimal and public consent not necessary. In cases such as housing, where larger investments are required, initiatives typically get stuck in a planning phase, making the space of the cooperative city more condensed. Cooperative is defined here not in the legal sense of the term, but as conveying the joint effort of various organisations and residents, a city that is shaped by its residents/users as much as it is shaped by its authorities on a daily basis, where classic uses of urban space are regularly contested.

Who does the city belong to? Fighting for and defining public space

One of the important issues for many third sector initiatives and their political/community goals centres around the question of who the city belongs to, who can exert influence on its development, and how. The actual answers might vary if we look at it from a perspective of decision-making or the point of view of the user. Part of the new trend of cooperative city management is to precisely blur the lines between user and decision-maker, where residents and civic organisations have a growing influence. There is also a redefinition of the public and private spheres behind this change, and many of the cooperative solutions are part of this trend, opening up formerly unused spaces, allowing city users to use semi-private areas.

Many third sector organisations focus on how public (civic) spaces can be used, by whom, and who can become real citizens in the city. Vulnerable groups often have difficulties using the provisions and amenities offered by the cities in CEE countries, thus there are many organisations focusing on issues related to this challenge. The main objective of the Budapest-based association The City is for All (A Város mindenkié) is to defend the right to decent housing for homeless people and people experiencing housing poverty, and their dignity. But part of their work with regard to homeless people actually centres on defining what, how and by whom public city spaces can be used.

The homeless are not the only group with limited access to public spaces. People with different handicaps – regardless of the age group – also face difficulties in accessing the city. Another Budapest-based organisation, MagiKMe was founded based on the experience of mothers with handicapped children unable to access playgrounds. Since 2015, it has created a movement for all inclusive playgrounds in Hungary, designing their own outdoor equipment, suitable both for healthy and severely handicapped children.

A further area, where the fight for the city’s future becomes more tangible is the discussion about the use of abandoned buildings. Schools, kindergartens and former factory buildings have become obsolete as a result of the changing city structure and the transforming needs of residents. Often in municipal hands, they stand witness of a former era. Finding a new use can be contested, and is deemed risky at times; nevertheless, successful transformations can pay big dividends. These transformations also showcase the new needs of residents, proving that they desire new kinds of public spaces: new types of offices and working spaces, community, entertainment and housing areas.

Multi-functionality, openness to the combination of different uses and the right to influence development is one of the most important requirements of cooperative city development. One of the biggest and earliest developments in the region has been the Sargfabrik (Coffin Factory) turned housing and cultural complex in Vienna, which opened in 1996 (followed by a second phase in 2000). It shows that there is a need to create a combination of uses, and the “village in the city” concept can be successful. As a strong bottom-up initiative that was realised following 10 years of planning, the transformation of the Sargfabrik area not only received support from the Municipality of Vienna, but also established itself as being one of a kind in the city. Although it was not a bottom-up initiative, the transformation of the Gasometer in Vienna can also be considered as being a similar endeavour from many respects, including the application of high environmental standards.

Such municipal support is typically not available for the CEE countries, so they often have to rely on different techniques. As the establishment of the theatre and circus centre Jatka78 in Prague in 2015 displayed, it is possible to involve interested residents in the formation of goals and create a cultural space as a bottom-up initiative, through financing via a combination of crowd funding, donations and a significant amount of volunteer work, turning an unused building into a new, multi-functional cultural hotspot. Similarly, the Jurányi Ház in Budapest, an incubator house for theatre and creative initiatives founded in an empty school building, although receiving municipal support, is run on a not-for-profit business basis. As a result, it not only stopped being a financial burden for the City Municipality of Budapest, but became a creative hotspot for the entire city, offering space for cultural start-ups as well as an accessible, open space terrace for city residents, representing a new kind of attachment to the use of public space from the residents.

The success of Jurányi – that a former school building could be transferred into an art incubator house – depended on the good networking abilities of its founder. Many third sector organisations can successfully operate only by exerting political pressure that could help give their initiatives weight. In case of the Old Market (Stará Tržnica) in Bratislava, hundreds of people watched online as the city assembly voted in favour of the location’s redevelopment. Redevelopment in this case meant that it would be transformed into a multi-purpose building, combining its original function with cultural and business functions and turning its management concept upside down.

From the perspective of redefining the public (civic) spaces of the cooperative city, another important area to consider are empty sites available for redevelopment. One possible use of such sites is by co-housing initiatives and building groups, who – depending on the exact nature of their contract with the city municipalities – can also create large leisure areas accessible to the public, and provide exemplary cases of integration. Formerly restricted to smaller developments, the spread of alternative housing solutions means that they are now capable of occupying and regenerating large plots of land, becoming a major force in urban development. These developments also mean that ecological and green principles gain ground in the cities. In Kreuzberg in Berlin, the Möckernkiez housing development was allowed to take place on a fraction of a former Deutsche Bahn land, creating 471 apartments in 14 buildings, an entire new neighbourhood. This particular Berlin example is interesting as it took place as a result of a long struggle, where political pressure was mounted by a grass-roots movement, and the influence of big developers was successfully counter-balanced. It is not so different from how political pressure is being exerted in the CEE countries.

Unlike big developments however, co-working and community spaces in general, have a more limited spatial requirement and as a consequence, they do not necessarily need the cooperation of the local municipalities. They can be opened up in smaller retail areas, and can be run as businesses, or in the very least, can recruit the support of business firms. Furthermore, the creation of such successful facilities does not often require large amounts of investment. These preconditions fundamentally influence the existence of many successful examples all over Central Europe, where they can be found not only in the capital cities, but also in important regional centres, providing work and office space for small companies while often trying to create a more collective atmosphere. As the example of the Nod Maker Space in Bucharest shows, investing relatively little into an unused cotton factory can be turned into an advantage. Similarly, cooperative farming and the supply of organic and/or local products supplied by local producers is also a theme that comes up very often among the third sector initiatives in the urban context. They do not really need the support of the public sector, and this relative independence contributes to their success.

The crucial role of the municipality

Despite the spread of new governance models, the influence of bottom-up movements has restrictions everywhere; after all, it is the city council that holds the political and administrative responsibility. Including citizen initiatives in the development plans, and fostering the realisation of these initiatives, locating vacant spaces for alternative and temporary use, opening up former institutional buildings for housing or other purposes have become priorities in many local governments in Northern and Western Europe. Most importantly viewed as being a part of the agenda to create more sustainable and equitable cities, by achieving public goals such as keeping the rental market accessible to all residents, the re-use of urban heritage, the regeneration of urban neighbourhoods by encouraging citizen/cooperative/third sector initiatives, or simply the provision of missing public services by the same means have become an important corner stone of many Western European cities in today’s Europe.

In the CEE countries, one of the most established third sector initiatives embraced by municipalities and various public stakeholders is community gardening. A case in Ljubljana shows that this is not only a great way to revitalise areas and foster community development, but it is possible to employ initiatives such as this as part of the social protection system. Born through the cooperation of the Municipality of Ljubljana and the University of Ljubljana, a pilot project was initiated in 2014 in which school dropouts (aged 16-22) were able to create and sustain a community garden and make it a community and bio-cultural hotspot. The project was supported by the Municipality by providing a piece of public land in the city’s Livada neighbourhood. The project has several aims to achieve by the end of 2017: developing the social abilities of school drop-out youngsters, creating an open air exhibition of biological diversity, and providing a place for community activities for the local inhabitants.

Municipalities in the CEE region rarely spearhead cooperative, progressive movements, but often allow them to be realised, complying with the “spirit of the times”. In most cases, bottom-up initiatives can flourish in the region when municipalities simply do not intervene. The development of the Jewish quarter in Budapest – an exemplary case of how a run-down area can be revitalised following the upsurge of private and third sector initiatives, and how later these initiatives are endangered by larger, more revenue-oriented developments – shows that it often takes a single good idea to jumpstart development. Starting as a summer idea, the temporary re-use of a vacant building and its inner court yard as a pub in the early 2000s collided with a big real estate surge of the same time and the Jewish cultural revival. The movement, soon followed by many more attempts, transformed the entire area dramatically within a decade. It turned a formerly dilapidated downtown area into a hip place, which today acts as one of the most important tourist attractions in the city. The quarter also gave rise to the most important and one of the most successful civic movements of contemporary Budapest, ÓVÁS, that was instrumental in stopping demolitions and preserving the built character of the neighbourhood.

Persistence on the side of third sector organisations seems to be a key factor in dealing successfully with municipal decision-makers. Recounting the story of how they acquired their first shop, and emphasising that the second time around it was easier, a founder of the cooperative shop Dobrze in Warsaw underlines this when recalling these initial difficulties quite vividly: “It was a big effort from our side: we went almost every day to talk with people from the administration. And then, probably because we were there so many times, somebody finally got interested in the idea and said ‘ok, let’s go for it’.”

The dependence of third sector organisations on municipalities in the region is acutely felt in the financial sphere as well. These organisations often need municipal support to (partially) finance their projects, or at least to help with the provision of favourable rental conditions. Behind the success of the cooperative solutions in Western and Northern Europe, alongside the already stressed relative openness of the public sector, there seems to be a very stable legal and financial background. The latter is in a rather preliminary stage in the CEE countries, and organisations have difficulty acquiring financing to up-scale their activities. Instead, they opt for using partially public funding – accessible through tenders – and rely also on municipal and donor support, the latter including large foundations and small scale donation schemes. These schemes are usually the closest to crowdfunding, but they never function as loans, partially because the national legislations do not allow it. In Hungary, for example, peer-to-peer lending is made impossible by current financial regulations. Furthermore, getting a loan is very difficult for third sector initiatives: despite their presence, ethical banks do not give very favourable conditions to these organisations. For their campaigns, all these organisations use social media, but often have to rely on their already existing network of supporters. A common problem they face is how to extend their reach and find additional supporters. Also, given their meagre financial situation, they often have to rely on municipalities for the provision of premises. There are exceptions to this: on the one hand there are a number of organisations situated between the private and civil sectors that operate with solid business plans and include “marketable” products, such as the case of the pubs in the Jewish quarter in Budapest or that of the Market Hall in Bratislava. On the other hand, cooperatives can have a stable revenue stream, and there are many examples of pubs or even farmers’ markets running successfully on a cooperative basis.

Concluding remarks

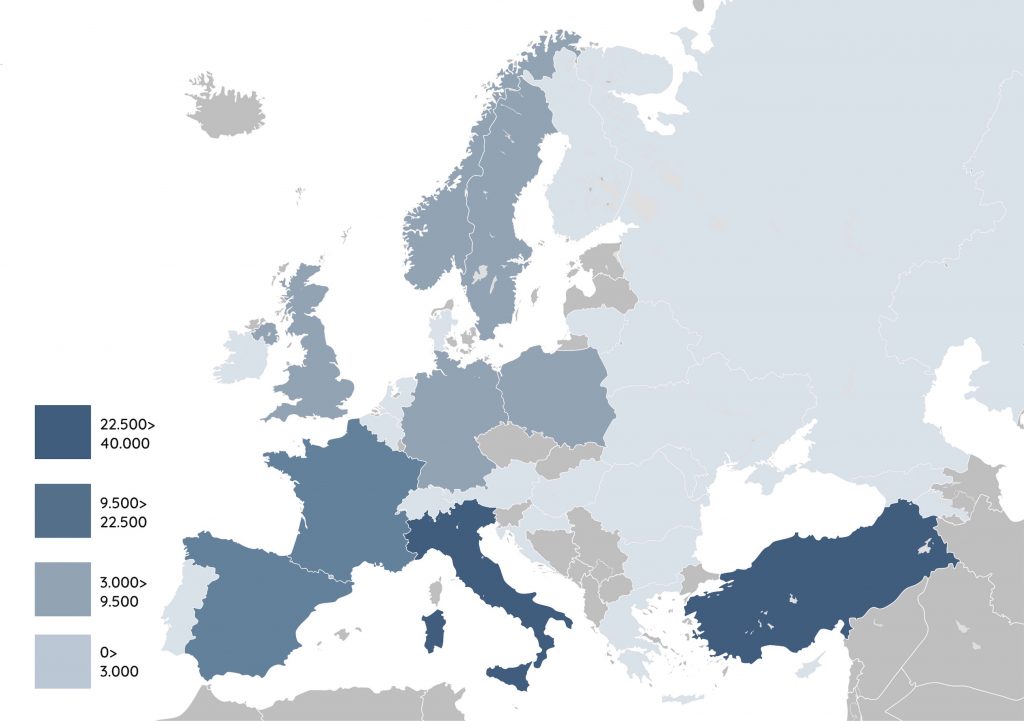

Despite an often reluctant public sphere, there are many third sector initiatives in the cities of Central and Eastern Europe, at times profoundly influencing the lives of the residents. The cooperative city in the making however is different from its Western counterpart, as the level of social responsibility seems lower, although the comparably lower income level of the region and the generally high share of groups at risk of poverty and exclusion – with the notable exception of the Czech Republic – would make a more inclusive tendency very welcome. In general, innovative social and cooperative solutions could present not only another way of using both public and private space, but can offer opportunities of development in neglected areas and the possible inclusion of marginalised groups in the cities. What seems to be self-evident in many of the developments in Western Europe – as expressed in the article in by the Sargfabrik and the Möckernkiez ventures – is more difficult in the CEE context.

An important explanation to this might lie in the availability of subsidy schemes – both of the German and the Austrian cases above made use of available public support quite extensively. Also, the lower level of social responsibility can be partly traced back to the general absence of some of the most important pillars of the cooperative city in the region: the missing collective housing scene, which is only emerging in the CEE countries, and the rareness of large scale cooperative development projects. Such projects would require, among others, municipalities with different approaches, banks more open to alternative developments and a more inclusive legal background. The housing market and the predominant legal regulations in the region do not favour the establishment of collective housing solutions either.

In addition to public administrations, financial institutions, regulators and investors need to change their attitudes as well: it is time to realise that sustainability in the long run is easier to achieve with more satisfied residents, and the success of a development project can also depend on the cooperation of residents. Furthermore, a more welcoming and flexible public sphere could provide substantial support for an increased social responsibility in the cities. The question when and how this change takes place will seriously influence urban development in the Central and Eastern European region for the coming decades.