Based in Amsterdam since 2008, CITIES Foundation has been working to address global urban development problems by implementing solutions at the local level. CITIES first research project, Farming the City, has evolved into a social enterprise for local food distribution service, Foodlogica. In 2017, CITIES published “The Wasted City,” a book exploring models of circular economy to manage waste, starting from plastic food packaging. Based on this research, the Foundation set up an experimental reward system in Amsterdam Noord, connecting inhabitants, local shops, the public administration and the recycling industry.

“We need to create the demand for recycled materials, that is the change we need in society right now.”

How did you start looking into food systems?

We started work on the publication Farming the City with the intention of exploring the problems of the global food system. We began by looking at the local food system in Amsterdam, dividing its territory into single food systems for each district. We worked with a lot with people, trying to understand what their food habits were, such as whether they liked the food in their district or whether they had innovative solutions for food-related issues in their area. We created a platform to broaden this discussion and performed a thorough analysis. The results were displayed as part of a huge exhibition, and for the first time all this academic knowledge about food systems, sustainability and localisation, became available to everyone. Here we showed all the results about the innovators of the food system in Amsterdam – what they want, what they need and what the next steps are. We talked about circular economy, as everybody does, but the point is this: how do we understand circular economy in the food system context? When looking at the food system for the first time we stopped looking at products and instead started looking at processes. For example, a piece of meat in front is not just a product. It is something that has been produced, processed, transported and finally consumed. Anything you consume in your life is actually a process as opposed to a product. That is the key to understanding circular city-making and the concept of the circular economy.

Everything can become circular if you look at the process that created it, so we started looking at the food system and farming. We gained a lot of experience from the people we met along the way; creating awareness about the subject and setting up educational activities and a variety of events, including a large event dedicated to local farmers. This brought about the realisation that we were not the only ones working on localising new food systems with the goal of making them more sustainable. Through our work on Farming the City, we looked at urban agriculture as a way to create more awareness about food systems within communities not as an economic solution, but as a social solution. The next big step was in the work of the Foundation: to be honest, all the examples shown are temporary, funded by subsidies, and ultimately not going to make any impact on the daily life of people. They might create a little bit of awareness, but people are not going to change the way they eat because of this. So we decided to analyse what food innovators were doing in Amsterdam. Everybody was working on consumption spaces like new marketplaces, areas, new shared kitchens for start-ups or production methods like biodynamic wine, special brewery or organic farming. But what about transport? An analysis was carried out by asking all the local farmers how they transported their food, and what resulted from this was what we called the ”urban farming food consumption paradox”: the more you eat local food, the more you congest and pollute your city. From a circular perspective, this is a paradox. So we developed, Foodlogica, and for the first time we stopped thinking temporarily, we stopped thinking about awareness-raising, but started thinking about intelligent, long-term solutions in relation to changing the system. We have since built a modular and scalable solution to transport local food brands within the city centre using rechargeable electric cargo bikes. We have been operating for 3 years now and experiencing rapid growth. Not only are we about to get new vehicles, we are attracting investments. However, while we are saving the equivalent weight of four African elephants of CO2 emissions per year, we are not making enough impact – we should become much bigger. This is the point: scalability becomes essential within economies of scale. Vertical integration and working more within the system is needed to make circular cities a reality. This is what we are doing at Foodlogica.

[flex_gallery id=”11821″]

Which other parts of the food cycle did you start looking into?

When you look at the food system, there is one big chunk that has not so far been mentioned, which is waste. Waste became so important that we could not address it within the Farming the City project. Focus was placed specifically on plastic, because in the Netherlands plastic packaging related to food is a very big problem. While researching plastic we discovered that this material had been invented as a sustainable solution back in the old days. Plastic is still a useful solution for some operations, but the problem is that within the consumption system, its use has become unmanageable. The cycle works like this: you buy a product, 95% of which is packaging that you throw away; you use the product hopefully enough to be happy with your purchase; you pay a waste management company to pick up your waste; your waste will be sent to China, where it will be recycled and sent back to you to be re-used and re-wasted. This is where everything has gone wrong. In 2015 we were focusing on new plastics, and we started asking people why they would or would not recycle, what would be an incentive to recycle more, what they think is never going to happen in their household concerning recycling and finally what were the toughest barriers to recycling according to them. We also approached institutions, cultural centres, sports clubs and all the local shops in the neighbourhood where CITIES’ offices are sited. We asked everybody about plastics. And through this research we produced a picture, followed by a thorough analysis of the social composition of attitudes towards recycling as well as an analysis the plastic policy in the Netherlands. As a result we identified three key issue areas:

1) plastic reprocessing – there is a big and wealthy recycling industry in the Netherlands;

2) lack of green urban areas;

3) lack of awareness concerning the issue of plastic.

Where did you start from to change the situation?

Children, students, families and even companies did not know how the cycle of plastic worked, so we created an educational programme called ”Plasticaholic Anonymous Meeting” asking people how many times they had touched plastic from the moment they woke up to when they went to work. It is unbelievable how many times it happens, probably you are touching plastic right now. We also organised a plastic archeology course – working with brands and students to help people understand the qualities of plastic and what are the best ways to recycle. The most important part of the project though is the reward system: having asked everybody about their consumption and their behaviour we came up with a solution, which we call ”win, win, win”. For every bag of plastic that people gave us we would give them a coin – at the time it was a plastic coin, made of recycled plastic, of course – and this coin could be redeemed in shops around the neighbourhood. This approach meant that we engaged with shop owners, who agreed to give discounts to people who would pay with the coin, creating a ‘thank you’ for their recycling behaviour.

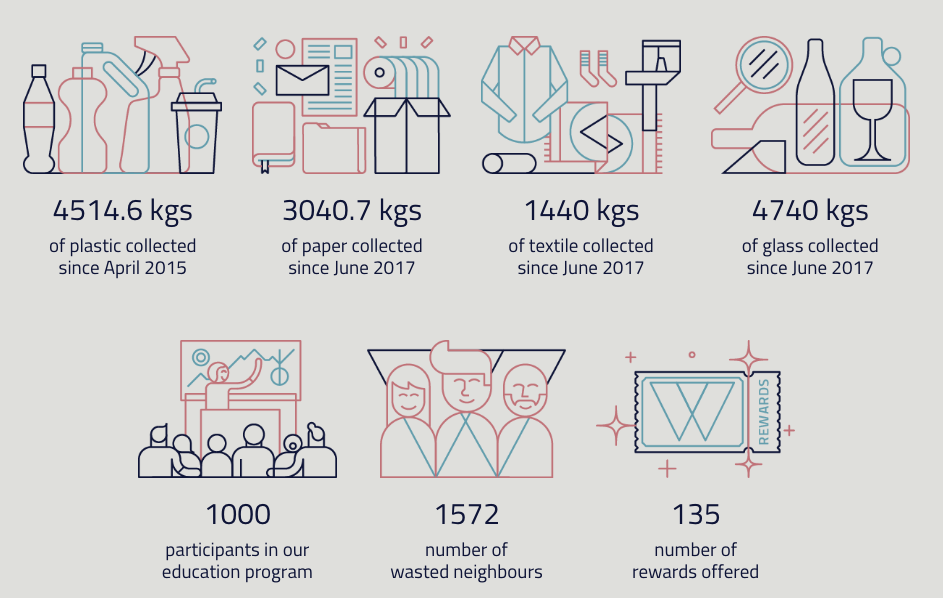

It was a very local project, but the World Economic Forum decided to feature it in a video. This video became viral with more than 20 million views and we started getting contacted by cities from all over the World, asking us to implement the plastic reward system in their local communities. Unfortunately, we could not, because this was a very small project, an analog system, which means that the actual management of this coin system is only possible when dealing with a small amount of households, not with millions of them, as it gets extremely expensive. So the Municipality of Amsterdam came to us and said, ”we love your system, you need to make it better and we need to work together. You cannot work only with plastics. We have four main streams that we collect and we need to raise the collection rates, so please work with plastic, textile, paper and glass.”

We agreed to the above, but we needed to digitalise the coin redemption process, something we are working on now with their support. So far we have digitalised the coin, and doubled the amount of households involved. Community management has become a very big thing. We now have someone on the team who is responsible for answering emails from people asking questions about how the QR scanner works. But we are making it happen and making plans to test all the rates, so now efforts are geared towards gathering a critical mass of people to use this system so that we can see how they use it. It is a long process, but that is what innovation is, especially when you co-create it together with a community. You cannot implement something immediately. The first half of 2017 was dedicated to creating the system. During the summer we were resolving technical bugs and doing what we called the Big Splash campaign in September and October. So, right now everything is coming together – almost 3000 people are using the system and starting to redeem their coins. We are also increasing the amount of rewards with one of team working three days a week solely on liaising with shops to join as WASTED rewarders. Another interesting thing about this system is that the coin value fluctuates: we do not give any precise value to recycling – it is the local shops that do that. Moreover, they love it because they feel they are making a contribution towards waste reduction, and benefiting the environment. In addition, as the majority of our subscribers are on welfare, shop owners also feel compelled to join because of how the scheme can support poverty alleviation while simultaneously attracting new customers.

We are located in Amsterdam’s Noord district, that is where we work very well. The WASTED coin is worth more than 2€, which means that your bag of plastic is valued at 2€ by rewarder businesses. Nobody would ever pay so much for unsorted, dirty plastic bags. In the center we are less active, so we outsourced the activity to other companies and what happened is that the coin value went down. Our activation campaign is not only about talking to people, in fact, we are activating low-income and diverse communities. For example, we are working with Arabic, Surinamese and Turkish centres, where there is no awareness about recycling. With the support of a local foundation, we have set up a series of workshops, where participants create artefacts out of their waste, helping them to understand that the waste has a value. So the point is: Trust people. Work with people. Work with the system. Our conviction is that the more work is carried out with local authorities, the better the system will be. We know this because at the beginning, when only working with plastic, we used to collect it by ourselves with our bikes. Once we reached 200 households, there were not enough resources, so we asked the Municipality to collect on our behalf, but once a 400 household-level was reached they said ‘we cannot invest in that.’ So, we rethought the system and the outcome inclusion in the Municipality collection system, meaning that we could totally cut that cost. That is the main point: we are a small organisation. As an enterprise, it does make a profit but as importantly, we make an impact. Waste should become a new social enterprise through which we are able to collaborate with more municipalities, creating localised campaigns for specific kinds of behavioural changes that need to happen.

The point of circular economy and changing the system is topical at the moment. The big players are needed now. Not only do we need the politicians and the policy makers, we also need accountants. And so, we have connected with PriceWaterHouseCooper, who are giving a lot of advice to Foodlogica. We are also starting to focus on how to transform waste into the crypto-currency of the future; a currency which has the potential to create social benefit alongside economic benefit. This is a major point for discussion: we cannot only allow ourselves to believe that the system is wrong, that it will never change and that we have very little say in matters that relate to our neighbourhood. We need to present these ideas to those who know how to handle big numbers and work with them to find solutions and create impact. This point was made in our latest publication, which of course is called The Wasted City, where we actually analyse circular economy and circular city making initiatives ranging from the very small scale to nationwide.

How do you collaborate with the City Council?

We are supported by the Poverty Department of the City of Amsterdam because our system is very good for low-income communities. However, the question remains as to how to overcome the fact that many of them do not have a smartphone to use the app. The coin system is still alive in Amsterdam Noord, but we are also working with the Municipality to resolve the smartphone issue. The Municipality provides a ”City Pass” for people on welfare, which gives pass holders access to discounts for cultural and sports activities that they would never have been able to afford on their income. The idea is that in the future this pass can be connected to the coin system. Once again, nothing was invented, we just asked whether they already had an infrastructure in place that we could link the coin system onto. It took a long time before the Municipality came back to us saying that they liked the idea. That was a long, rocky road, but now a very nice and open discussion exists about how to connect all these significant layers using their infrastructure to create innovation. Whether this is going to happen or not is another matter.

Within Europe production based jobs have been disappearing. However circular economy is something that will create and generate new jobs for low-skilled workers, who are needed for production activities. While there may always be some economic disparity between regions, circularity allows for economic processes that are substantially more beneficial for smaller and poorer countries. As such countries are less dependent on globalisation, they can adapt to circularity with ease.

How do you collaborate with the Private sector?

At first, we ran a local reprocessing lab, where we made objects out of recycled plastic, such as a tree planter. That tree planter would usually cost lots of money when made with raw or virgin materials. Seeing the opportunity, it was at this was point that we got in contact with the local recycling industry. This is vertical integration; we make sure that people recycle, whilst the recycling industry ensures they have enough material to actually have a viable industry. However, one organisation cannot do all this by itself, the circle has to be connected. The problem is not that they do not have enough material, but that they do not have enough requests for recycled plastics. That is the big problem for that industry. One of the goals of our Wasted Project is to encourage our members to buy products from brands that use recycled materials in their production. However, encouraging behaviour change on a larger scale is not yet happening. It is an issue at European level, because politicians blame companies, while companies say that there is no market, so in the end it is the consumers’ fault that buying products that use recycled materials is not part of routine consumer behaviour. This is why we have to integrate the old circle and work with everybody, however, the challenge is to build demand for recycled materials. That is the change we need in society right now.

Interview with Francesca Miazzo on 15 October 2017