The city of Naples (Italy)[1] is an exemplary case study of how a city can co-design legal and sustainable urban commons governance mechanisms and enable city inhabitants and local communities to act collectively in the general interest. In 2011, the City of Naples enabled the activity of a network of local communities in Naples that informally manage publicly-owned spaces in different areas of the City, by turning the latter into spaces for artistic exhibitions and urban welfare services and recognising them as urban commons. The City developed innovative legal design principles, governance arrangements, urban policy tools to do so. The toolkit developed through this experience was later recognised by Urbact as a best practice in urban sustainable development and became the pillar of an Urbact transfer network, “Civic eState”.

The case of Naples is centred around the transformation of building complexes and urban welfare services in urban commons. Its innovation potential consists of enabling collective management of urban essential facilities governed as urban commons through a public-community governance approach. Such approach secures fair and open access, co-design, preservation and a social and economic sustainability model of urban assets and infrastructures, all to the benefit of future generations. Collective governance is carried out through the involvement of the community of neighbourhood inhabitants in designing, experimenting, managing, and delivering new forms of cultural and social services.

This article will situate the historical context of the commons in Naples and then discuss the governance arrangements that the city has experimented with and valuable lessons for commons regulation that can be applied elsewhere.

1. Introduction

Before the work of the political economist Elinor Ostrom gained global prominence, the governance of the so-called ‘commons’ was seen as a difficult task. Hardin in The Tragedy of the Commons describes how, when individuals have open access to resources that are non-rival and non-excludable, they will act according to their self-interest, contrary to the common good of all users. Elinor Ostrom however, undermined this assumption. She provided examples of how communities from Switzerland to Nepal were able to effectively manage common pool resources by establishing a shared set of rules and norms.

While her examples mainly concerned natural resources – such as irrigation waters and forests – a plethora of urban commons have emerged in cities around the world. Naples is one such city that is experimenting with different forms of governance suited to the commons. Home to seven formerly empty buildings turned to civic use, Naples is the lead city of URBACT Civic e-State transfer network – a three-year-long network transfer among six European cities aimed at disseminating knowledge on how to create, manage, and maintain urban commons. Naples defined urban commons as tangible and intangible assets, services and infrastructures functional to the exercise of fundamental rights considered by the city of Naples as collectively owned and therefore removed from the “exclusive use” proprietary logic to be governed through mechanisms of urban co-governance based on the legal tool of the “civic and collective urban uses”.

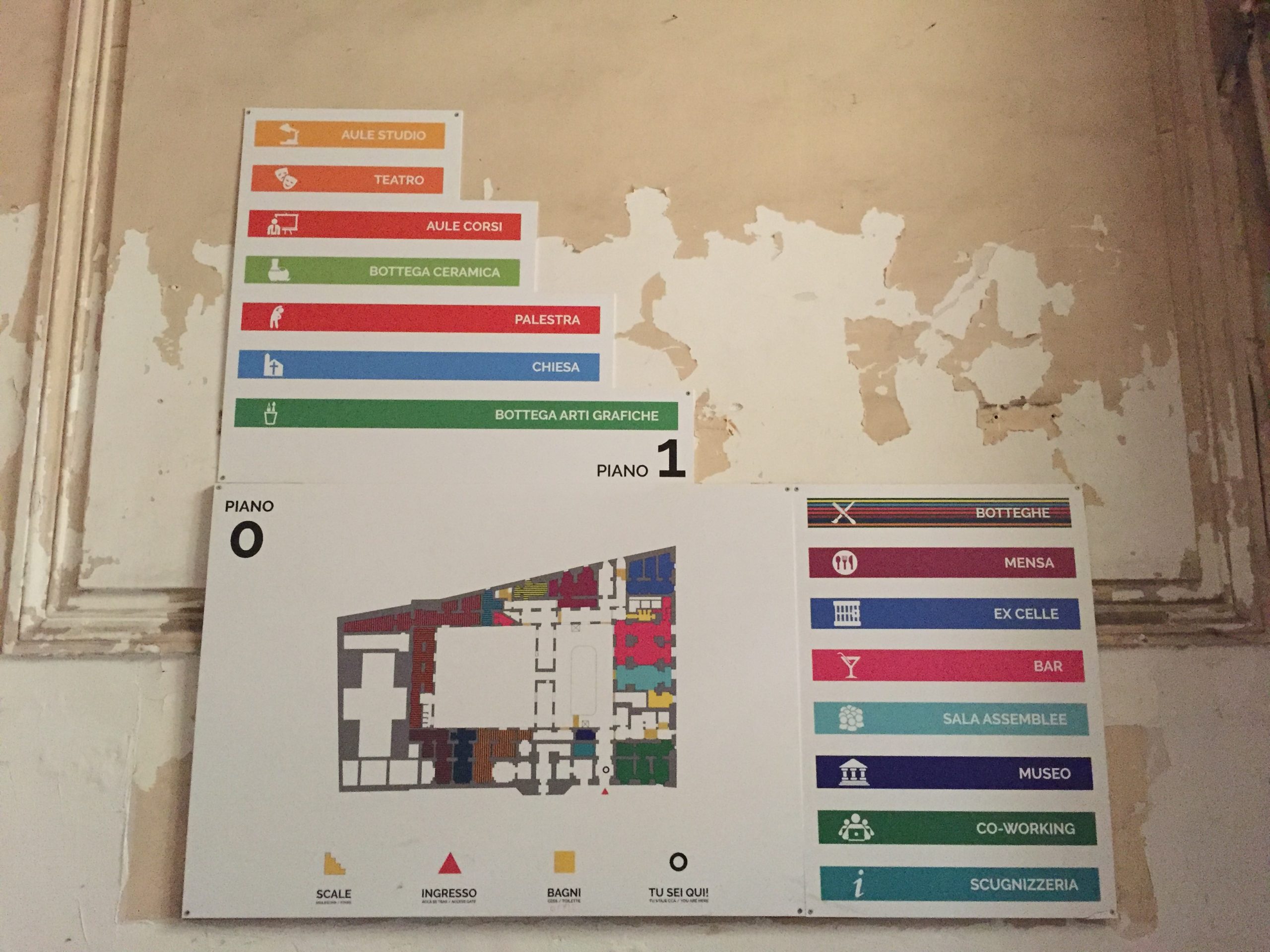

Naples’ journey to the urban commons started in 2012 with the informal management of a former convent called ‘Asilo Filangieri’, a monumental building in the city centre owned by the City of Naples. The community that started the informal management of the space was composed mostly of artists who opposed the high unemployment and precarious working conditions of the cultural sector. The building had been lent to a Foundation in charge of organising the UNESCO’s Universal Forum of Cultures, an event that occupants thought did not sufficiently make use of local cultural assets. Rather than conceiving the building of the Asilo Filangieri as simply an ‘occupied space’, occupants started seeing it as a common. They transformed it into a cultural and arts centre and made means of production (for example theatre stages, crafts material) free and accessible to all.

2. ‘Civic use’ as a legal tool for urban co-governance

The vision of the City as a commons that the City embodied, shaped the Scugnizzo liberato case, another collectively occupied building, through a self-governance tool, the “Civic and collective urban uses”. The Asilo commoners, in close collaboration with civil servants from the Municipality from a Department for the Commons (created in 2011 by the freshly elected Mayor Luigi de Magistris as part of a broader strategy to promote commons in the city) collectively wrote a Declaration of Urban Civic and Collective Use’. The Declaration establishes the usability, inclusiveness, fairness, and accessibility of the Asilo spaces and infrastructures.

This model is a system of urban co-governance that intends to go beyond the classic “concession agreement model” which is based on a dichotomous view of the public-private partnership. Civic and collective urban use recognises the existence of a relationship between the community and these public assets that triggers the formation of a social practice eventually evolving into a “civic use”, which in essence is the right to use and manage the resource as shaped by the practice and concrete use of the common resource by its users. This process makes community-led initiatives recognisable, creating new institutions, ensuring the autonomy of both parties involved, on the one hand the citizens engaged in the reuse of the urban commons and on the other hand the city administration enabling the practice. The policy was implemented through a series of City resolutions starting with the Asilo experience in 2012. The Declaration of the Asilo was recognised by the resolution of Naples City Government n. 893/2015 as the public regulation of the building. By doing this, the local administration “recognised not only a mere access entitlement but also the rights to the direct administration of the building itself”[6]. The process culminated in 2016, with a new resolution (n.446) enabled other public spaces to adopt the civic use model of the Asilo and be declared as ‘emerging urban commons’. In addition to the Asilo Filangieri, in fact, seven public proprieties were recognised by the City Council of Naples as “relevant civic spaces to be ascribed to the category of urban commons”: Ex-Convento delle Teresiane; Giardino Liberato; Lido Pola; Villa Medusa; Ex-OPG di Materdei; Ex-Carcere Minorile – Scugnizzo Liberato; Ex Conservatorio S. Maria della Fede; Ex- Scuola Schipa.

Civic use is an historical legal tool used in rural areas in Italy to grant certain communities collective rights over land and pastures. Essentially, this model recognises the existence of a direct relationship between public assets and the community itself and gives the latter the right to use and manage them, consistent with the nature of commons[2].

It is important to note that the City administration does not abandon its role in the Naples’ commons framework. According to the Declaration, the City instead provides the possibility for the compensation of management expenses “and what is necessary to ensure adequate accessibility to the property”. This is justified by the fact that commons like the Asilo generate social value by providing welfare and services that are in the residents’ general interest. The City of Naples, in other words, recognises the ‘civic added value” (redditività civica) of these initiatives and thus contributes to supporting them and enabling their practice. In the first five years, the Asilo offered 7,800 public initiatives, and targeted 260,000 beneficiaries. All spaces provide cultural and creative services as well as urban welfare services such as primary health care or legal counselling for migrants and vulnerable people. The spaces’ management relies on shared rules and principles for the use of the space. During the first pandemic outbreak in the Spring of 2020, the City relied on urban commons to support its action of relief for the population of Naples, offering shelter to homeless and delivering food across town. These spaces turned into commons constitute the civic patrimony of the city of Naples. The main design principle in the activities’ scheduling is the non-exclusive use of any part of the property. No property can be assigned to as operational headquarter to any subject or group, not even temporarily, and everyone will be granted access to the space on a rotational basis.

3. The challenge of a sustainable urban co-governance mechanism.

The mechanisms agreed by the City of Naples, although rooted in the Italian legal system, are characterised by a high degree of adaptability to other urban contexts. In a theory of the City as a Commons, which adapted Elinor Ostrom’s theories on the commons to the city context, Sheila Foster and Christian Iaione identified three features for effective collective governance, which are all present in the case of Naples: sharing, collaboration, and polycentric governance.

Firstly, collaboration was key to the success of the establishment of urban commons in Naples. Direct collaboration between the City of Naples and Asilo users was crucial to establish a framework for civic use and outline the new role of the City administration as an ‘enabler’. Collaboration is also at the heart of the day-to-day management of the Asilo. The users become problem solvers and resource managers that are able to make strategic decisions about common assets and to implement them with other citizens and other urban stakeholders.

Finally, the day-to-day management of the urban commons reflects a system of polycentric governance. This means that resources are neither exclusively owned nor centrally regulated. Rather than having a top-down management system where organisations on the ground carry out mandates and are accountable to the city government, the Asilo belongs to the community, and it is governed by different bodies that reflect such community. At the same time, there is a certain level of interdependence between the City of Naples and the Asilo, as the administration commits to pay for some of the expenses. In other words, in a polycentric system of governance, the State takes on enabler’s role, providing the necessary tools for urban commons to flourish and generate social value while maintaining their participatory and open-access nature.

The use and informal management of these empty buildings by the urban communities implied on one hand a temporary use of such places and, on the other hand, it created a stimulus to start searching for innovative mechanisms for the use of such spaces as a community-managed estate. The latter feature is the main object of the role of Naples as lead partner of the “Civic eState” URBACT Transfer network. To recognise and implement forms of organisation and urban co-governance, by creating an innovative dialogue between administration and citizens started and building a process of co-creation, not just of legal tools and governance arrangements, but of economic-financial tools that can ensure the medium and long term sustainability of the spaces.

References

[1] Naples is the third most populated city in Italy, after Rome and Milan. It is the capital city of the Campania Region and the metropolitan area of Naples. Characterised by urban sprawl, and with poverty concentrated in the central area of the city (rather than in the periphery as is the case in Milan and Rome), over the past decade the City of Naples decided to invest in the reuse of existing historical city centre heritage.

[2] Ugo Mattei and Alessandra Quarta, Right to the City or Urban Commoning? Thoughts on the Generative Transformation of Property Law, The Italian Law Journal No. 2 (2015); Giuseppe Micciarelli, Introduction to urban and collective civic use: the “direct management” of urban emerging commons in Naples. Heteropolitics International Workshop Proceedings, http://heteropolitics.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Conference_Proceedings_Website.pdf.

Christian Iaione, professor at Luiss Guido Carli University, faculty co-director of LabGov – LABoratory for the GOVernance of the City as a Commons (www.labgov.city) and lead expert of the EU Urbact program for the Civic eState project.

This article appears in the book The Power of Civic Ecosystems: How community spaces and their networks make our cities more cooperative, fair and resilient.

Watch this video about the commons initiative Scugnizzo Liberato in Naples, created within the Open Heritage project.

The Convento delle Cappuccinelle & Scugnizzo Liberato from The Open Heritage Project on Vimeo.