“The trick is how to translate the masterplan to something that people can understand”

The Estonian city of Tartu has recently created a new masterplan. For the Tartu Municipality, an administration with a strong focus on citizen participation and a long-term engagement with the digital transition, this was an occasion to call for proposals and suggestions from the side of citizens and community groups. We spoke with Jarno Laur, Deputy Mayor of Tartu in June 2017, at the occasion of the Interactive Cities network’s visit to the city.

How did you bring your participatory vision down to practice in relation with Tartu’s masterplan?

We created something not very theoretical but rather a practical example of public engagement, of having discussions and lot of information to and from the citizens. The issue we wanted to address is the new masterplan of the Tartu city and usually a masterplan is something is too abstract to attract any real interest from citizens. Because usually it consists of a series of maps, maps themselves are abstraction, and not many people can read maps functionally. I have a paper copy of the city’s masterplan, the text is something like 240 pages of rather heavy text but the masterplan is a crucial document for cities and for citizens as it directs new developments, changes neighbourhoods; it effects our lives in all possible ways. So the trick is how to translate the complicated text and maps to something that people can understand and feel they have really something to say about it and to translate it so that it is still the same text and that you don’t simplify so it doesn’t become misleading.

How do you do this?

What I try to do this time is to use all kinds of technology to try to involve people more in the process. First of all we had official invitations to the public, announcements of the plan but we also had funny things because it should always be funny. We made a campaign that featured some statues in our city, all statues of important people of Tartu asking different questions about the future of Tartu from each other and from citizens. The whole point actually is to ask really simple questions that will normally rise when you are discussing this… We asked the same questions that normally people ask about the future of the city and we did it a funny way, just to have people share it on Facebook and social media, it was an imitation of public debates, nothing more. We also had nice posters displayed in the streets, giving the process also an official feel, and used all the possibilities to spread the word, through the city’s social media accounts and our personal Facebook pages, trying to get more fun into the process and get local newspapers intrigued. If you are making a masterplan there is certainly intrigue in that.

How did all this communication feed into the masterplan?

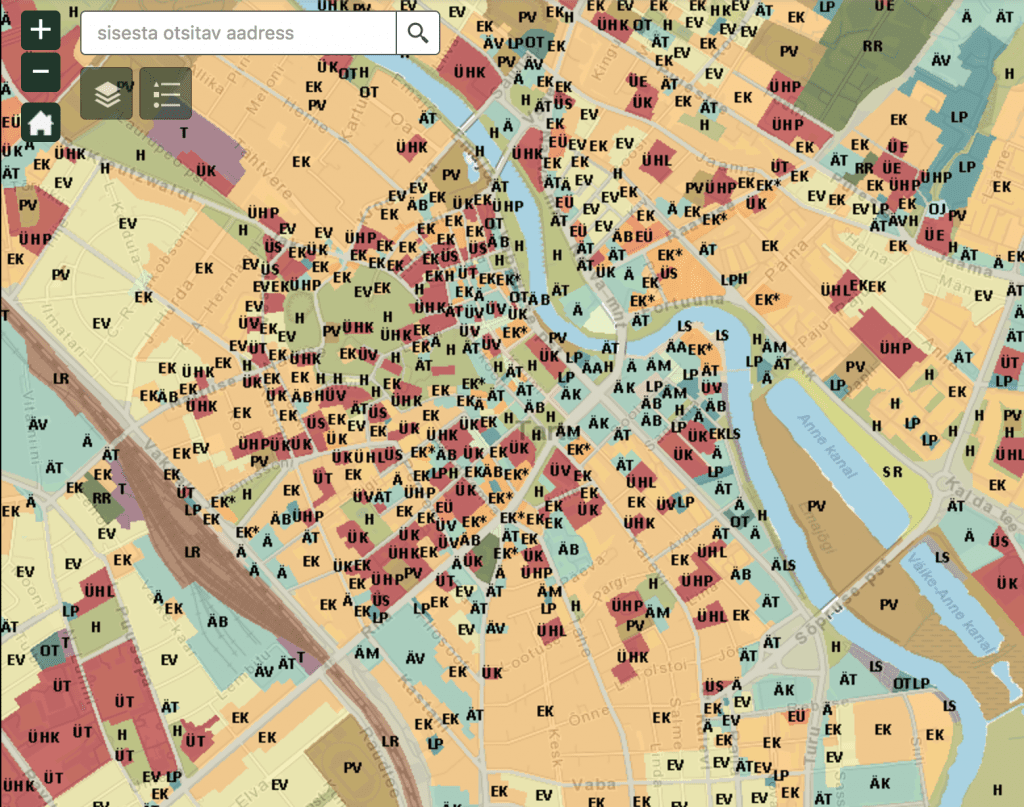

We created a special subpage for the whole process within the city’s website. We decided not to have any paper copies as we normally don’t have paper documents, only digital documents. We followed this logic also with the masterplan: we created a really good digital map, a special map that contained all information. Everybody could see the main points that we wanted to make with this document. In Estonia the masterplan normally includes 20 or 30 different maps in paper version. But in this version we don’t have 20 or 80 maps, we have different information layers, so that everybody can switch them off or on and they can compose map that they will use. For example we have special maps for main roads, for bicycle roads, for schools and social infrastructure; normally, if you have paper maps you can’t combine those, you have to look at one paper for roads and another for schools. With this one you can switch the different maps, and combine them, for example you can see maps of schools combined with bicycle roads and that makes it easier for citizens to understand and to know what is going on. Because you can translate it to the focus and more narrow issues that you are personally interested in. For example we have a special kind of protection for old neighbourhoods: the city that has wooden neighbourhoods, almost all of them are protected. People are very interested in which houses are under protection and which are not, so you can switch off other layers and can switch on the layers that show which are protected houses: for example, red houses are under national protection, the green ones under local protection. You can zoom in to your own house, you can understand what is going on with your plot and the neighbouring area.

How do you handle the maps and data within the administration?

We normally try to develop open platforms, but in this case we decided for an existing proprietary platform. What we are ensuring now – and this is a decision we made – that all data connected to the localities, any maps that we have in our offices are all based on the same platform and they are all layers on the city map. A lot of departments are actually involved with this. We have one person in our IT department who manages all the issues with our system and helping departments to start using it; and normally in every department there are one or two officials who are fluent in that language. Of course the planning department – that is natural – but also the communal services departments and the department of education are heavy users of these maps. It is important to have one single platform for all the data. Before we used to have different applications for different things: street lighting had its own map, program and platform and the masterplan was in a totally different format – it is not going to work. You need to decide on one platform.

Do citizens have access to this data besides the maps?

With the new webpage we also have a lot of open source data. Actually the beauty of the Estonian system is that all data is open. If you want to see who is owning a plot, you just register online and you can see who is owner, what kind of other things are there. If you would like to know what your neighbour is planning to build, you just need to go to the national register for construction and you see all the permits that are issued. Now you can see even some data of the design, but not all of it. I would say if there is some data you can get it. The problem is that some of the data is not always correct: land use datasets and the building register that contains data from the 19th century, for example, is not always correct so if you are processing the case of a house from the 19th century then we also need correct the data during the process, but there are not many cases like that.

Could you include feedback from citizens in this map?

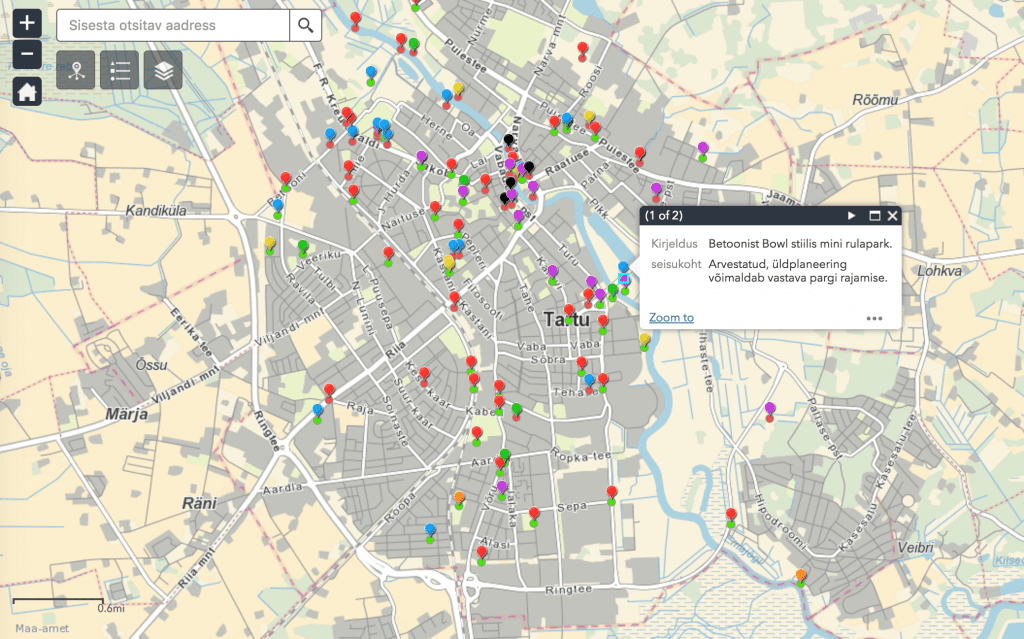

Yes, we tested it for the first time here. We used a map of the city for gathering ideas, for example if someone would propose a playground to a certain area, or a beach to the riverside but doesn’t know if this topic is relevant for a masterplan. We created the possibility that whatever idea you have you can use this forum to show the place and you put your idea there, with only a few words. Everybody can then see the ideas that were added there. We had more than 100 ideas collected this way that would normally not be presented because to use a very official way, applying for amendments of the masterplan, the process itself is tricky, you have to write an officials letter etc. We tried to lower the barriers for people simply to submit their idea and the rest is up to officials. I must say most of their ideas were great. I was a bit afraid that if you give this type of opportunity they will be more or less about being against something. Usually people are against something but this time it was surprisingly constructive.

How does the administration process this information and how are these ideas connected to the participatory process?

It is kind of the same procedure as the participatory budget. It is an input for us about problems, ideas and possibilities. We gather the suggestions and then we take a decision on every proposal. They can be decided to be included in the masterplan, or not, in case the topic is not for a masterplan or ‘we can’t do it’. All the proposals get an official reply and we summarise the replies. Many many ideas were about some kind of fields of public space, playgrounds for dogs or children, beaches, so many of these things are in process already, but it was really good input for us to see that when we are making the budgeting for the coming years, we can emphasise more precisely what people are interested in. In that sense it works exactly the same way as the participatory budget because the idea of the budget is of course to implement great ideas but it is also important to have a feedback about where the problems are.

Were there any conflicting suggestions from the side of citizens?

There were places with contrasting ideas, for example, where a dogs’ playground was proposed. Half were in favour and half against. That’s democracy. But then we have really good partners, a neighbourhood committee from the area that organised a couple of meetings, discussed the ideas with different people and decided to support the dogs’ playground in the end. We could certainly identify some problem areas with many pros and cons and different ideas: it is obvious that we should concentrate on these areas more. I think next time we will also give a chance to everybody to evaluate the ideas of others. This time the idea was to put suggestions on the map, people could read but couldn’t react to it, next time we will make it more like Facebook, so that you can hate or like the idea and we can get more feedback.

What was the timeline of this operation? Did it require more time than a regular masterplanning process?

Actually the procedures are set by the law. You need at least six weeks for public debate and display. Normally the law says that there should be at least one discussion before the six week period and one after. We tried to do a bit more, so we had about twelve. The next thing was a leaflet sent in every postbox in Tartu, listing the ten most important things we will change with the masterplan and indicating the time and place for the public discussions and per topic. For example we had discussions concerning traffic, especially bicycle and pedestrian traffic as this is the one of the key areas we focus on, we had a special discussion on protected areas and another one on universal design and accessibility. Then we had regional discussions concerning the neighbourhoods. We went to the school, the library or the stadium and discussed about the challenges about that particular neighbourhood.

How do you structure of a meeting like this, how can you encourage people to be more constructive rather than conflictual?

We gave a lot of information beforehand and had a lot of discussions with neighbourhood organisations. They were doing a really good job, not only in getting people to these meetings but organising pre-meetings, having discussions on their own and presenting their proposals. We also made available the summaries of the meetings so that everybody can read them. Before the final public debate, we produced a video summing up the previous meetings. The process was finalised with taking an official stand on the more than 200 pages of proposals. We also had a meeting where all those who made the proposals came and told us what they were thinking and we explained why we took one decision or another. It is not without contradictions, there are many of them.

Interview with Jarno Laur, Deputy Mayor of Tartu

Tartu, 2016.06.07