Right in the heart of an inner district in Budapest lies a 7700 square metre wild, at first sight untamed green space, sandwiched between unassuming residential buildings. Walking in the area, one is surprised to find Szeszgyár, this vast ecofeminist and queer community garden behind the graffiti-filled walls, away from sight. Szeszgyár is different to most community gardens. Its core principles are rewilding and ecofeminism, placing the initiative in a unique ecological, political and social context. Its community encourages us to rethink our relationship with our environment as collaboration rather than destruction or exploitation, and overcome binaries such as “human/nature” or “natural/unnatural”. The space is located on the vacant grounds of a long-abandoned distillery factory where it gets its name “Szeszgyár” (Distillery factory). The owners of the plot have given permission for the group to use the land until it is sold. In this interview we speak with Adriam, one of the garden’s current caretaker, who tells us about the history of the land, the role of the principles of ecofeminism, queer ecology, permaculture, and rewilding in revitalising the land, the relationship with the municipality and neighbours, and the precarious situations they have to navigate within Hungary’s political landscape.

Can you tell us about the history about this wild, green space in the middle of the city?

This space used to be a distillery factory for a very long time. So the name of the space and the street makes reference to that. The factory was functioning for a long time, but like many other factories in Hungary, during the regime change and democratisation process in the 1990s, it was sold to foreign capital, and then not long after it closed down, and was left vacant. Later it was purchased by a new owner with the purpose of reselling for a much higher price to build new, luxury apartment blocks. It is a massive space, with 7700 square meters. It has been on sale for 20 years already, and has not yet found a buyer.

What are the conditions of use and do you have a contract or deal in place? How long can you stay here and use the space?

There were some conditions of course, like long-lasting structures cannot be built. We can stay here until it is sold so there is no rush. The price is too high, but the owners want to sell for that price. I think eventually they will be able to as this neighbourhood is going through steep gentrification. 10-15 years ago, you couldn’t imagine what this area looked like, just 15 minutes walk from here were run-down houses inhabited by very poor people, now luxury apartments and malls stand in their place. Housing prices are increasing sharply in Budapest so they know it’s going to be so much more expensive in the future. Plus, just in the last couple of years several new buildings have been built in the near vicinity of Szeszgyár, so the owners know that they will be able to sell it for the price they want. And in the meantime, they are relaxed about us being here as there are no upkeep costs. The costs are with us, we are paying for electricity and water through renting an adjacent ground floor shop.

How have you found this vacant plot?

Anna Margit, the founder of the project rented initially the nearby shop, and turned into art space. During a movie shoot, when the garden was left open and transformed into a lively scene from 90’s Berlin, Anna had the idea to call the land owner in the hope to make this space just as lively in real life, not only for a movie set.

The owner agreed after some negotiations to give the space for free to open a community space. The land was filled with mountains of rubbish, Anna, together with her girlfriend Elise, and friends organised cleaning days. During COVID these events became as a safe outdoor space for gatherings. Originally the idea was to start a community garden of sorts and a bar however the activities became political in a way, reflecting on the very visible social inequalities around the garden, on the situation of women in Hungary, the social and climate emergency, the arrival of refugees from Ukraine. The loudest issue however became the most personal, the persecution of the LGBTQ community by the government.

This plot has been on sale for about 20 years. What issues or challenges might be delaying finding a new buyer?

Speculation. The owners are asking a price that currently seems unrealistic, but they are ready to wait until it will no longer be. In addition, there is also toxic waste that needs to be removed. The disposal of toxic soil is a big issue in most countries, which might also play a key role here.

How do you create a sense of community at Szeszgyár?

The garden now is in its 3rd year, and the strategies keep changing but the main thread have probably been to offer refuge for those who are otherwise not welcome in this city. For example, in the first year from the vegetation being left to grow, many insects, birds and other small animals moved in, but all vanished when the summer droughts hit. The response in the next year was to build a natural pond, to take care of the new inhabitants, as part of our community.

Another important position is towards our queer community. The space being called a queer garden loud and proud, when there are no other such places currently in Budapest have been important for many, providing a sense of solidarity and community by simply existing and being visible, despite all. Among the neighbours of the land, the project is popular because they can bring compost, come walk their dog, play with their kids, watch movies and join evening concerts. We try to offer a something for everyone and question what it would mean to have a truly public park.

How is this space different from other community gardens?

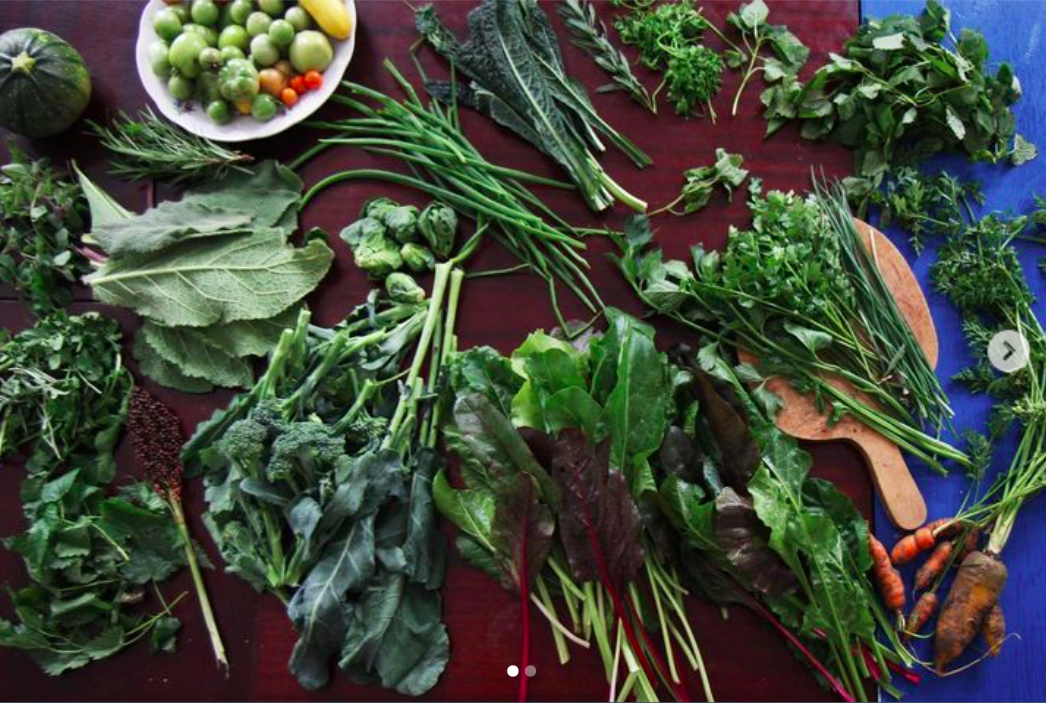

As you can see this is not a typical garden. There are a lot of wild plants growing here. We want to rewild the place, having a very positive effect on biodiversity. There are plenty of insects that you won’t see anywhere else in the city but here. As you have so many insects there are also birds and bats, and because they are here, we end up having very few mosquitos. They all enrich biodiversity. There is a lake here, and sometimes ducks come through from the nearby Orczy garden, or from the City Park. This space is rich with wildlife.

Szeszgyár identifies itself as an ecofeminist space. Can you tell us about the ecofeminist guiding principles?

It is a theory that comes from feminist and queer theory. In the capitalist hetero-patriarchal system there are many harmful binary understandings such as the opposition nature and culture, man/women, that is then used to establish hierarchies, and justify oppressions. Ecofeminism tries to identify and break those binary understandings and remediate to the exploitation that is justified by these binaries. It looks at for example how industry and culture exploit nature, how we can work in different ways, more as part of the same ecosystem and not outside of it.

We are also a vegan space, cooking only vegan meals but also ask those who host events here to respect this. For us, veganism is part of ecofeminism: we say no to animal exploitation, especially factory farming, that is usually justified by human needs being claimed superior and generally linked to poor working conditions for precarious workers.

We work on the basis of regenerative farming, which means we try to have a systemic approach and for example don’t use any kind of artificial fertilisers to force productivity. With regards to ecofeminism, it means we try to see how we can be a beneficial part of the little ecosystem that is developing here. Not outside and separate from ‘Nature’. We are not doing anything to “get the most” out of the land. We work with it.

We build and garden with reused materials ‘foraged’ in the city. The soil came from excavation sites for building new houses, we used the wood from a nearby house that was demolished, and we get plenty of compost and leaves from neighbours and so on.

We are also very proud of the outdoor mud stove It works with minimal wood and stays hot for long. A supporter of ours who built it is active in fighting energy poverty and builds these stoves in segregated villages, where people lack access to gas, electricity and adequate amounts of wood.

One of your core principles is rewilding, which means restoring an area of land to its natural uncultivated state, with the reintroduction of indigenous species that disappeared in the past. Can you tell us about the biodiversity of this space and its connection to rewilding?

We see this a bit differently, because the idea of restoring land to an uncultivated state with species ‘intended’ to be present can be part of a harmful narrative. It reinforces the idea of people being separate from ‘nature’. Ecosystems are in constant shifts: plants, animals, humans included are in a constant migration and the idea of having a stable past state is very new. One of the main issues with this narrative of the pristine wilderness is that it takes away the agency of indigenous people. When we remove people from the equation it creates a sense of apathy, that we can’t act in the face of climate emergency but only do harm, so we better not even try. The idea of removing ourselves as people from the landscape, because we only do harm, is used around the world to persecute indigenous people and remove them from their lands, while granting access to the most privileged to national parks destined for entertainment. In reality, before the boom of capitalism, people lived as part of the ecosystem, the term and notion ‘Nature’ is pretty recent itself, dating back to the18th century and the work of Alexander von Humboldt, a German naturalist. We try use the term ‘nature’ critically.

In Szeszgyár, the idea is to observe what grows here, and see how we can help the biggest number of species to thrive. With the pond, the idea was to act as important part of this small landscape and do our share of helping others to live here. Then, there are also invasive species who are particularly adapted to survive despite the harsh conditions. Many are amazing at living where no one else can, but they also tend to reduce biodiversity, even when conditions could become favourable for others. Wanting to foster a biodiverse environment, we try to remove the more competitive or invasive species. Plus, we are asked by law to do so.

We started to work on an herbarium also, because in the 3rd year of the garden it is absolutely astonishing how many different grasses and wildflowers found their way here, despite being in the middle of the city. Here, in such an urban context, the term ‘indigenous species’ doesn’t really make sense, nothing is supposed to live in this concrete desert.

What kind of people are drawn to Szeszgyár and form part of the community?

It often feels like there are many different Szeszgyár, with everyone taking away different things from it and using the space in different ways. There is of course the queer community for whom it is an important spot. The garden also hosts a lot of different organisations who are working against the political tides of Hungary and take shelter here. Generally, however the common thread is the desire to take an active role in shaping our society and being critical of the current systems we live in. Or just simply people who want to have a pleasant time in a park that gives more than the mostly bleak public parks of Budapest.

What activities do you do?

On our Facebook page we have over 200 events advertised but there were way more than that. The biggest hits were probably the two ecofeminist festivals, the queer markets, the evening concerts, the community cookings when we cooked vegan food for Ukrainian refugees, the movie nights and of course the collective gardening sessions.

How do you manage the land financially?

In the first year a lunch delivery of seasonal, local vegan food was organized, and the revenue was used to pay the rent of the store front shop. Then in the second year, we managed to get several fundings, from ICLEI Europe, Budapest Pride, CEU, the district and the city, but there was also quite a lot of private donations. Many of the organisations that bring events are often also able to donate a bit. There was a bank for example that paid quite a lot for a team building day, in addition to digging a big chunk of the pond. We also take donations during events but to be honest it doesn’t really make much because the idea is to keep the space accessible and free, so in these situations even those who can afford to give don’t. Overall, it’s manageable.

What kind of expertise do you have in the core group managing the space?

We have a former biology teacher, we have an expert on composting, we have an expert on mushrooms as we do a lot of work with mushrooms. One of the volunteers is an architect and knows about landscape gardening and how to create a park.

Do you work or collaborate with any institutions, municipalities, schools, or universities?

We work with institutions such as the kindergarten just the other side of the walls and also the 8th district municipality. For example, there is a Hungarian tradition that they burn a doll to just “scare away the winter”, a tradition that takes place in spring. The past two years the municipality has organised this event here. The municipality also has collaborations with organisations that have events here. Schools can also visit and check out how they could use this space.

What kind of expertise do you have in the core group managing the space?

Anna who started the garden is an architect but quickly oriented towards gardening. Elise, whom she has been mostly managing the space with is a nature conservationist. The others in the core group are working in community organising and participatory landscape design, alternative farming practices research and ecofeminist theory, and many are artists and educators. With two other people, I joined the team when Anna and Elise moved to Berlin recently. I am a translator who also works with people experiencing homelessness.

Do you work or collaborate with any institutions, municipalities, schools, or universities?

Luckily, the district municipality, which governs in opposition to Hungary’s government, have been collaborating with us since the beginning. They also sometimes bring their own events, for example, there is a Hungarian tradition of burning a doll to “scare away the winter”, in the spring. The district brings each year all the kindergarten students for this gathering. We are also in close collaboration with Budapest Pride whom with we co-organised many of our events with. Anna and another key team member, Flora, have also been teaching a course for MOME art university about vacant lot uses.

Can you give some examples of collaboration with other organisations?

We collaborate a lot with the nearby Gólya, a collectively run bar, cafe and community space. We co-host events with them when they are looking for outdoor spaces, such as the Midsummer festival. Together we manage to reach more people, but they also brought sound systems, drinks, and people who helped during the event. Gólya also brings their food scraps to compost weekly, and we even cooked for events they hosted in their space. With everyone being underfunded we find the best way is to put together our resources and find ways of helping each other out. We don’t have a lot of equipment but always find organisations to borrow from whatever we need.

How do the infamously anti-civic, anti-LMBTQ+ Hungarian government institutions and media view your activities?

Not well. There are politically motivated conflicts. Anna and Elise moved to Berlin for this reason because they received a lot of death threats and were simply burned out from the shear amount of work it takes to keep afloat a space named ‘queer ecofeminist community park’. The mayors or both the district and the city are very sympathetic to the project, but elections are coming up and Orbán’s party doesn’t shy away from using the garden for propaganda purposes and smear campaign started. To give some context, there is an annual fascist celebration taking place in February where fascists from all over the world travel to Budapest and gather at historic sites. This year, a number of antifa protesters travelled from Germany to confront them. There were allegations that some fascists were beaten by a number of antifa protestors. This caused a major uproar in the government media, and they started a smear campaign against all leftish organisations like Auróra, Gólya and us. The campaign went on and on. The tension was terrible.

What is your relationship with the district?

The local mayor would like to help by renting the garden officially from the owner and providing much needed support after the main organisers left. Let’s see where this goes. However, the landlord and the district administration is not in good terms, because of the ripple effects of the smear campaign. The district is under a lot of pressure from government media due to being a progressive, left wing opposition administration. Imagine, when we have a huge smear campaign against us, the neighbours are worried, and they talk to the district and start to put in complains. At the same time, the district is suing these papers, because they are providing completely false information. So there is a lot of tension, and we have to navigate in this atmosphere.

What is your relationship to the neighbours?

It started off really good in the first two years, but sadly in the 3rd seasons things got a bit hard to manage for the reduced team, who also had less experience with the tricky field of neighbourhood relations and community organising. With the smear campaign, lack of time next to our full-time jobs, and a few loud late night events by a university group, the relationship started to deteriorate. In addition, a few of the neighbours keep throwing in trash that we don’t have the capacity to keep cleaning up, which is also negatively viewed by the neighbourhood at large. When in the garden, we try to keep inviting in those who got alienated from the garden due to recent events, to talk with them and hopefully will have the capacity to start a campaign to make the outreach more effective, making the space sound more interesting. This would include distributing fliers in post boxes, posting on doors or public areas, and continuing conversations.

Finally, can you tell us about your personal involvement with Szeszgyár? How did you end up here?

I knew the place for a long time because I live near by. I started to come to events and later I also started to volunteer at organising events. I already had an interest in permaculture and eco-feminism. I came here because of a mushroom workshop, learning about how to grow mushrooms at home. That always interested me, my actual family comes from a small village, and we always worked in the fields. If you’re a person who has that kind of history you want to continue doing that. It had been a while since I couldn’t work on the fields so that was a really important point. When Anna and Elise moved, and others who stayed had less energy, I jumped in to help with taking care of the space. Three of us who were not yet in the core group got together and decided to do our best to keep the space open and functioning.

Interview with Adriam Magro (2023), and Szeszgyár founders Anna Margit and Elise Heral (2024), with the article published in 2023, and extended and updated in 2024.

UPDATE 2024: While the project has suspended operations, Szeszgyár has inspired other smaller scale initiaties, and former members have started new garden projects elsewhere in the city, whiile others have kept organising events at other venues working with the topics tackled by Szeszgyár.