Local Operators’ Platform (LOCOP) is an independent initiative and research lab specialised in cultural research. LOCOP’s aim is to critically assess cultural policies and transnational funding programmes according to their real-life effects for local cultural operators and sustainability. It offers in-depth experience in practical cultural management both in independent and institutional frameworks, as well as specified research tools for the evaluation of cultural processes based social sciences and policy studies.

One of its main research focuses is the European Capital of Culture programme (ECOC). LOCOP aims to highlight the importance of local community involvement as a bridge between the ECOC’s top down management strategy and the local organisations’ bottom-up approach. While the programme is successful mainly in its effect on the economy, cultural heritage, urban planning and tourism, the participating cities’ long-term cultural and social development has been overlooked. LOCOP is an educational, capacity-building and empowering platform for both ECC stakeholders and also for the local scene. In this interview, co-founder Szilvia Nagy explains the platform’s aims and objectives through its flagship project, the Valletta Design Cluster.

Why was LOCOP established?

The idea came in 2014 when I met lots of local cultural operators from different European Capitals of Culture programmes (ECOC). They were activists, artists, organisers and what they shared was a common disappointment about how their local scene was benefiting from the ECOC experience. People were facing the same issues but they didn’t have a shared platform or output to share and discuss problems or to act upon them. They felt their experience was personal and separate from other cities’. LOCOP tried to offer a platform to these actors based on the shared notion of their experience.

The LOCOP project came into existence because of this inconsistency between the vision of the European Capitals of Culture brand and how local operators felt, how they experienced this process. I would not contest the European Capitals of Culture idea as an idea. But in its implementation, it didn’t work that successfully on the local level. There is an inconsistency because the envisioned participatory nature of the programme was not really fulfilled. There was no room for the kind of participation that many local operators or civil society organisations would have liked to see.

By uniting these local operators, we managed to take the issue to a different level. We believed that we could change the structure by naming it. What LOCOP does is a mediation process between government officials or programme managers and local operators. It offers a participatory action research framework, where we try to involve these different stakeholders to find collaborative solutions to the issues.

You work a lot with secondary cities – cities that applied but didn’t win. Instead of feeling an inevitable disappointment, what is the best way to transform this energy into something sustainable?

The cities have high hopes, as they engage in a long process to prepare their bidbook (the application material for the title). As it is a long and transformative engagement, but also a competitive project, it is very disappointing when they don’t win. However it is useful for the cities to see that there are cities that are transforming on their own initiative after their bid, in a bottom-up way. The strength of ‘secondary cities’ is when they don’t give up on cultural transformation and community projects, but try to re-scale their programme to a smaller scale and still carry on with the community-building and participatory civil society approaches. They don’t have as much involvement with politics and usually have the more sustainable examples with more transformative power.

What happens with the European Capitals of Culture is that when the title is won, usually the political stakeholders take over. Until that point it is usually working as a bottom-up cultural initiative, with local and municipal support. When the title is won and the programmes are starting, it requires a bigger infrastructure and organisational capacity. These new offices and infrastructures stay at place until the ECOC is over. Then there are the next years when only some follow-up programmes happening. In comparison to this, when we focus on something smaller it can be more sustainable and it can have a more transformative power. We can see it as a comparison between a top-down and a bottom-up strategy.

Do you have an example to give us?

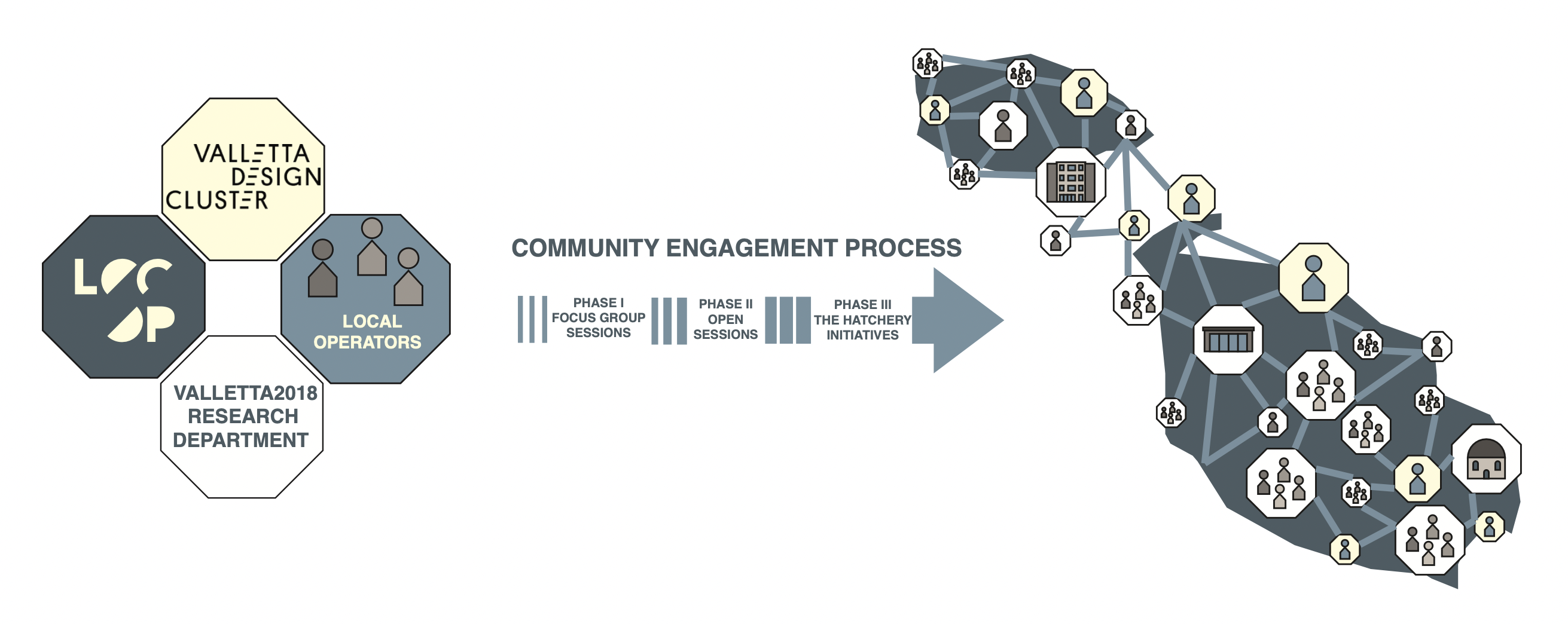

One of the most recent examples is our collaboration with the Valletta Design Cluster which is a community space for cultural and creative practice situated in the renovated Old Abattoir building in Valletta, Malta. We collaborated with the research department of the Valletta 2018 Foundation, the Valletta Design Cluster and various organisations through different workshops, focus groups sessions and activities to establish and map the needs of civil society in relation to the planning of a new institution, the Valletta Design Cluster. It was an amazing learning process for all participants, and it lasted for two years. The Valletta Design Cluster could learn about the inhabitants living around the institution, about what their needs were, how they would envision this place; and also about the needs of the artists and local operators and how they can find their role in this new institution.

How did you get involved with Valletta as European Capital of Culture?

In 2015 we had a symposium with LOCOP in Budapest and we invited people from different cities who worked with the local scene, upcoming or current European Capital of Culture cities. Valletta was an upcoming Capital of Culture, we invited the Research Coordinator for Valletta 2018 Foundation, Graziella Vella, who at the time focused on local involvement and research aspects of the European Capital of Culture year in Valletta. She liked our approach which is based on research and collaboration, and thought it could be something interesting for Valletta. She invited us to their next conference and while we were there I met with the representatives of the Valletta Design Cluster and our collaboration started.

How did you design this several years-long process?

When we started working on it, it was already the year of the European Capital of Culture in Valletta. They had an interesting situation where the Valletta Design Cluster was the planned flagship project. Albeit it was planned to be ready for the ECOC year, the renovation and planning process was delayed. This gave an excellent opportunity to not only involve the local civil society in the planning process, but also to reflect on the shortcomings and pitfalls of the local operators’ involvement in the ECOC year. Therefore, the European Capital of Culture year gave a good opportunity to start working together, in a collaborative way with civil society to establish this cluster. It gave funding and programming opportunities to develop a long-term collaborative vision and helped us to think through the whole operation as a collaborative process. This was based on participatory action research. We proceeded in stages, by identifying programmes and research schemes, initiating actions and prompting feedback to inform the next steps. In this collaboration, the Valletta Design Cluster was open to this process without a visible end point. Throughout this collaborative process we could not only involve the civil society, but also reach a deeper involvement in the planning process. It led to actual programmes and spaces that people were requesting.

Who participated in this process?

We had a different group of participants for each phase of the process. In the beginning, we launched an open invitation to cultural operators and civil society activists. We ended up with a very mixed group, mainly local cultural operators, people who are primarily affected by local cultural programmes and therefore are interested and active in the cultural field. This was our starting core group. Later, throughout the process, we additionally tried to involve local habitants and civil society in general. When participants joined a session, they were directly invited to the following ones, which were open also for newcomers. This resulted in a core group with eventually returning participants for every couple of meetings.

What were the different phases of this process?

The first phase of the involvement consisted of a series of focus group sessions where we used the method of “issue mapping” to identify different problems in Valletta. We had different groups working on urbanism, issues related to artists and artworkers, some issues related to the liveability of the city such as walkability. The issues were identified by the groups themselves and they could start working on the most urgent problems with our help. The focus group sessions allowed us to specify a number of specific themes to work on and also to identify broader ideas like that people would like to have access to workshops with tools in the Valletta Design Cluster.

In the second phase, after the focus group sessions, we had larger events that were combinations of a presentations and a civil consultation, held in a school and joined by people who couldn’t attend the focus group sessions. These open sessions were organised to discuss further the outcomes of the first phase, including more viewpoints.

In the third phase, we brought together the micro-level of the focus group sessions of the first phase and the macro level of the open sessions of the second phase. Here we worked with a different kind of strategy and asked people if they had any knowledge, skills or tools to offer or share with others, organised around the themes identified earlier: Maker Culture (with an emphasis on woodworking), Social Innovation, Food, Education and Placemaking. We also asked about participants’ needs, what is it they would like to learn from others, or offer to them, be they language exchange, food or cooking classes. We started to organise action-oriented events focusing on these interests, under the title Hatchery Initiatives. When we had the demand and the offer both popping up we just tried to match them so people can sufficiently organise themselves later on without our help. The Hatchery Initiatives were just the first spark to situate these offers and needs and to bring people together around topics that they already identified they are interested in and willing to develop further.

Once you have the topics and the match between demand and supply, how does it all feed back into a broader cultural ecosystem?

It all fed into a set of collaborations around the future Valletta Design Cluster. For example, the food related hatchery was not just about the know-how or about cooking something together. It also served as an education platform about what are the locally available fruits and vegetables, about local fish cultures, community gardens, the intangible heritage of the place and all the venues connected to this heritage. We identified many simple issues where we tried to bring in aspects of sustainability and locality.

The food topic will also be followed up in the Valletta Design Cluster where the original plan was to have a catering place, which later transformed into the idea of a community kitchen where people can prepare food together. One idea was developed further to have community breakfast on of the open bridges in Malta by a very devoted team, where the main focus was different kinds of communities and subcultures coming together and bringing together something for brunch. It was based on cultural exchange, also involving refugees. All these themes contributed to shaping the new institution, the Valletta Design Cluster.

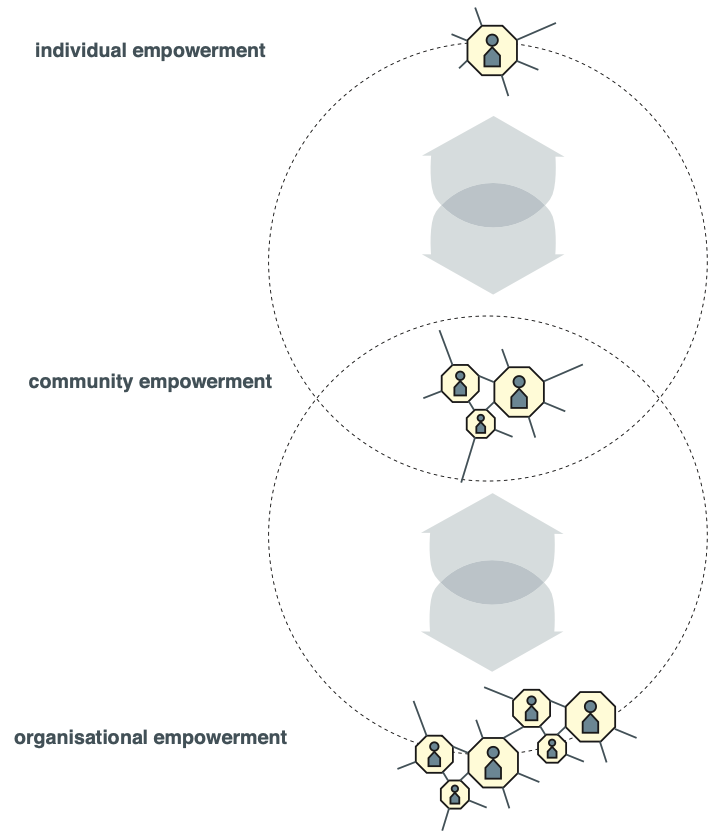

How could this process contribute to empowering local operators and their communities?

When we talk about empowerment, we are aiming for self-empowerment, to give a situational reflexivity to people about how community building can enrich their lives and make them visible. The idea is not to have intermediaries to empower people but for people to self-organise themselves around topics to see the power of self-representation. Such a process could be, for instance, connected to the power of unions, labour associations where people can self-represent their interests at the city level or even internationally.

What was the policy outcome of this process?

Participatory action research is not aiming at a final policy outcome but is an ongoing process. People continue to work on their position in relation to the whole cultural field and in the Valletta Design Cluster but on the other hand we also formulated recommendations to inspire policy makers and local representatives could take. These recommendations focus on community involvement and entrance points to empowerment platforms, networking and collaboration, access to information and public assets, non-formal education and knowledge exchange, alternative economic models, cultural sustainability, participatory decision-making and evaluation.

How did the project continue after you left?

The legacy is up to the people. Some continue and some don’t stick. But the Valletta Design Cluster is there, the building’s construction has been completed. The plan was to open it at the end of 2020 but unfortunately, it was delayed with the pandemic. When it will be possible to work in communities, these different groups will come alive again. The legacy is also in terms of the people who participated in this knowledge production. They see how it works, how participatory democracy processes work, they recognise a power of unity and collaboration among each other.

Interview with Szilvia Nagy, project manager and founder of Local Operators’ Platform (LOCOP).

This article appears in the book The Power of Civic Ecosystems: How community spaces and their networks make our cities more cooperative, fair and resilient.