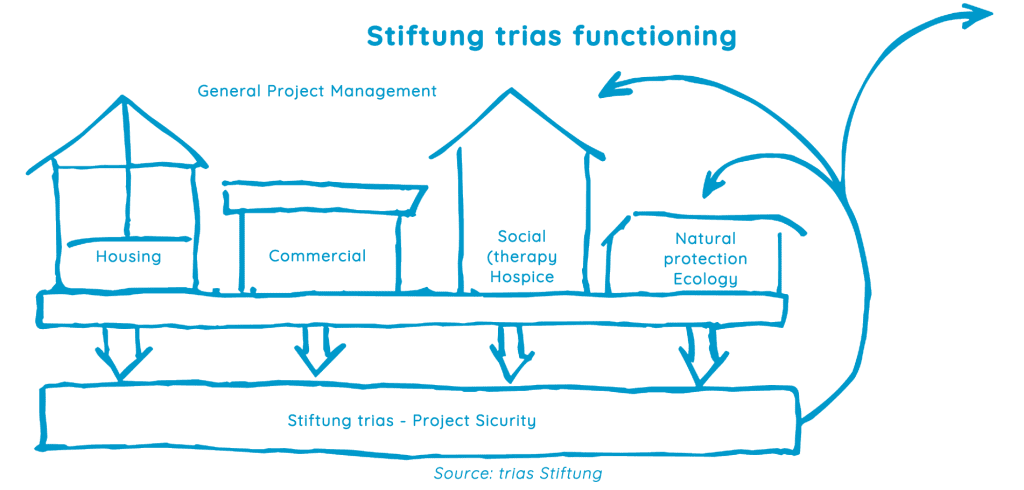

Stiftung trias was established in 2002, to help community groups and co-housing projects access financing. Trias takes land off the market by separating the ownership of land and buildings: supported initiatives lease the land from the foundation in the form of a long-term Heritable Building Right (Erbbaurecht) and their lease fee is collected in a mutual fund run by trias, where capital is accumulated for further property purchases in support of like-minded initiatives. In recent years, trias has also been working with public administrations, securing functions for properties that municipalities are obliged to sell under austerity laws.

“When we buy properties, our goal is to secure spaces of freedom”

This interview is an excerpt from the book Funding the Cooperative City: Community Finance and the Economy of Civic Spaces

How was Stiftung trias born?

We established Stiftung Trias in 2002, because all the co-housing projects had many problems and deficits, and we tried to work on it. We did not have a big founder, a donor, like in the case of a classic foundation: we were a Bürgerstiftung, established by a couple of professionals, like me – a banker –, consultants, and umbrella organisations like the FORUM Gemeinschaftliches Wohnen in Hannover. All of us realised that there were many difficulties in accomplishing co-housing projects: there was no relevant literature, no money, no network. All the initiatives, after moving into a building, forgot everything: and a significant amount of knowledge was lost. We knew it was not our job to create another co-housing project but to collect this knowledge, give people involved in such projects more handicraft, and more abilities to realise their plans. We thought that if we could build up sort of a solidarity fund – to conceive our foundation as such a fund –, with each project, it would be easier to start the next one. We also realised that there were a lot of unsolved issues around heritage and donations, as well as land issues: many people contacted us about how to move properties off speculation. We organised a workshop and came to the conclusion that the best format to work on would be a foundation. As a non-profit foundation, you can just collect land and buildings, pile them up as assets, and use the revenue of these assets to support new projects. This was the idea: we collected 70.000 euros from our network and started this small, non-profit, idealistic organisation. The foundation is growing. We started with only 70.000 euros and we now have 7.5 million of our own capital: people trust us and we are getting bigger. We have also collected a lot of knowledge. We have also become aware that a good reputation resulting from all the projects we previously completed helps us as well.

What does trias mean?

Trias is taken from the Greek language. It means we have three aims: the three columns of our foundation are community-oriented living (participation and self-organisation), a different way of handling land (no speculation and no building on agricultural land) and sustainability. These core values did not change in the last 15 years.

What is the foundation’s main objective and how does it work?

Foundations usually work with their revenues, but we soon came to realise that we have to work with our assets as well. We discuss more about how to invest in our assets than what to do with our revenues. We invest all the money we receive in land and building sites – or we purchase an old building needing restoration, together with groups. When we buy properties, our goal is to secure spaces of freedom, because the prices are getting higher, international capital looks for good investments and finds it in real estate. So they buy everything they can get, and there will be not much left for initiatives. On top of that, municipalities – not only in Germany – are running out of money, and with their budget cuts, they cannot or do not want to provide space for artists, social initiatives and people with low income.

Who are the initiatives you support?

One of the most important things is that the groups we deal with are not profit-oriented: they belong a certain segment of society that is convinced that making as much profit as possible is not the right way to run a society. We usually do not have to search for nice projects because so many projects approach us themselves and ask us if we could help buy land for them. They have to speak with all the people in their group to receive confirmation that it is all right to work with us. Nowadays, it is possible to get a loan with an interest rate of 2% plus repayment of another 2 %. So commercially speaking, it is not so attractive to pay us a land lease fee of 4%. Many initiatives prefer to take a loan and buy a building themselves. To work with us is an act of solidarity: after 30 years, when they repaid all their bank loans and do not have any debts anymore, they continue paying the land lease fee into a solidarity fund. It is an idealistic step: not only do we help projects, but projects also help us by building up a structure for the next project. With each project that comes into the foundation, we are getting stronger and we increase our ability to do more.

How do you start working together?

It usually starts with a phone call or an encounter at an event, like the Experiment Days. If the project sounds honest, I always suggest them to look into our profile, if they really want to belong to our network and like the way we work. If they agree, first, we ask for information about the initiative, ask around people who know them, and usually visit them to get the full picture. During these visits, I rely on the experience of all my previous loan conversations as a banker: I do not only talk to them but also inquire about who the people who manage the project are, do they have enough own capital, how many people support them. As a former banker, I am trained to ask such investigative questions. If I really do check them, it is not only because I am responsible for the donation, but it is also a question of their economic sustainability.

Second, we usually only purchase the land when the project can prove to have bank financing, so the bank checks the economic sustainability as well. Sometimes the people who run the initiative allow us to talk directly to their bank, and this allows us to exchange our knowledge and help each other figure out the best options. But the most important is to have a friendly feeling for the project. We cannot look into the heads of people, so we just have to go by our feeling, if they are really honest, non-profit and engaged in the topic. Usually it takes between 6 months and 2 years until the whole process, including the purchase, is done.

If we decide to join a project, if it comes into the “trias family”, we can then invest personnel capacity: we can join them in crucial situations, such as meetings with the municipality or the mayor, we can join them in conversations with a bank, help them with their financing sheet, help find their legal form, and assist in defining the financial instruments. We look at the evolution of their finances and if possible, adjust our land lease fee to their abilities, to make their initial years easier. In turn, once they have more possibilities to make payments, we will ask for their help. It is really about working together.

What legal forms do you use to secure land from speculation?

Usually, we keep only the land, and the project takes over the building. We use a very well-known land lease contract from England, but not only: German churches use it often as well. The land lease contract is our preferred form to work with. This is because we advocate the idea that land is common, and should not be the property of private persons, not even a cooperative; and the land lease fee or the profit you get out of the land should be given back to the society. The land lease contract has two effects: first, we get a land lease fee and that enables us to do our work. Since we are not able to purchase the land solely with donation revenue, we have to take loans, and we repay the loans from the land lease fee. What remains, covers the costs of our work. Second, with a land lease contract, we have a kind of security-contract with the group. If they are telling us that they plan a housing project with handicapped and non-handicapped people, or ateliers for artists, we can give them the land for that purpose only, and if they want to change the use, they have to speak with us first. It is not that the use cannot be changed, if it does not work, but we have to go into a conversation with you, what else could we do, it must be something social, useful, helpful and idealistic. Due to the fact that so many people aided in the construction of your house, we feel that we have to protect their original ideas and all the monetary assistance, efforts, work and knowledge they put into your project; so we are the watchdog for idealistic aims.

How much influence can you have on what is happening in the buildings?

The building itself should be run by the people who live in it or who use it. So I do not think that our foundation should give directives to the building to be green, blue or white: these are all the matters concerning the people living there. I think the freedom provided is that there is no owner who could tell you what you have to do. You can decide how much you will you renovate, how high your rents will be, how you are going to use that building and things like that. In each situation, you have two different paths: the project on one side and the donation on the other. There is a polarity of interest: people of cooperatives care for themselves and for working “in their quarter;” we, on the other hand, have the responsibility of looking much further ahead, looking into the scene, and maintaining the theme itself. This polarity creates a certain tension between the two partners that is inspiring, and enables us to help in conflicts.

Besides owning land, do you also own some of the buildings you work with?

Once in a while we do have constructions other than land lease contracts, when we receive a building or land as a gift. In Berlin, for instance, we received a building site and the donor suggested that we build a building on it, since everything was prepared for this undertaking. We decided to seek financing, asked GLS Bank in Bochum, and developed a social building for mentally handicapped and ill people, with a kindergarten and a repair café. In this case, we are simply owners of the building, where we create social content and also earn a modest revenue. To receive a yearly revenue of 10.000 euros from a building that cost us 4 million, is very little. Nevertheless, we are very satisfied with it because of the social use of the building. But in the long term, of course, as we obtain more assets, it will also gives us more opportunities to donate. In this sense, there are always exemptions from the regular way we work, we just have to be creative. Like when we receive a piano or a violin as a donation and have to look for the best way to make use of it.

Who are your partners in raising money?

We have a quite a widespread partnership. Some banks, like the GLS Bank in Bochum where I used to work, have been partners from the beginning. But after 10 years, we realised that we had very few bank loans, and much more with other foundations and private people. Many people support us with friendly interest rates. We conducted a considerate amount of marketing in the past years, and people in the co-housing field got to know us just through our work and activities. We received many requests to buy land for co-housing projects, but we rarely have freely available money. Instead, we suggest them to talk to project participants, friends and people around their project, and ask for loans or donations: it usually brings together a lot of small amounts, 3-4000 euros, and sometimes there are people who are able to give dozens or hundreds of thousands of euros. But donations almost always come from people within the scene: they already have a basic understanding of our work. Some people with inheritance or shares in cooperatives come to us and offer us a donation: all the 70-80 large donors we had, have a very specific story, a personal reason why they give us money or property. People see us as an independent institution, and that often helps in creating the necessary trust. There are also tax advantages involved in donating, but I think this is not the main motivation. At the same time, with all the advertising, we do not receive much money from ordinary people, because our targets are too complex, the way we work is complicated to explain and co-housing does not sound like a public goal for them.

How do you keep track with all the projects you supported in the long term?

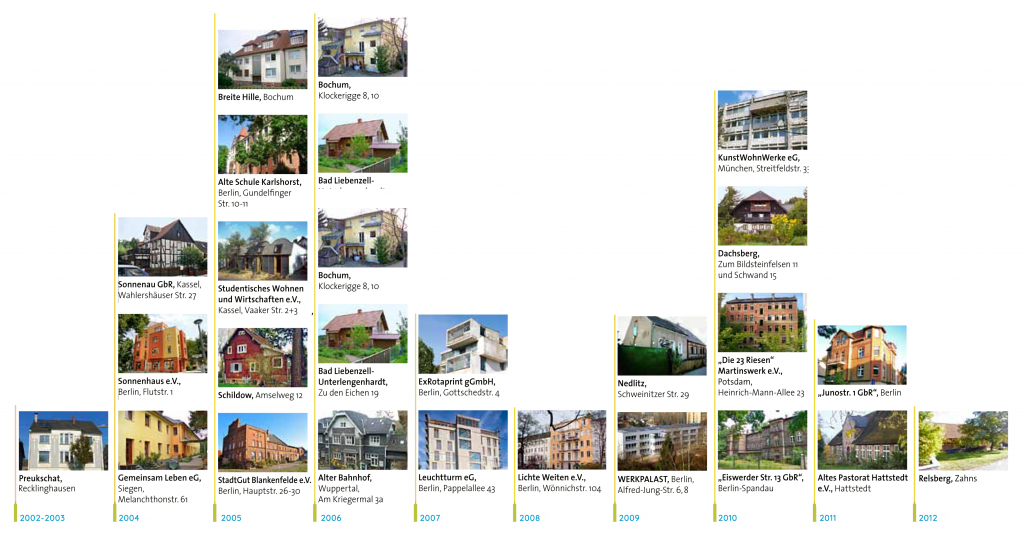

With land lease contracts, we are the watchdogs of the initiatives: we regularly check if they keep the functions agreed on in the contract. When we do not check them, we lose the right to press on fulfilling the contract. We try to visit them once in a while, and of course with so many projects, it is getting complicated, and turning into a lot of work. If I wanted to visit all of them once a year, I would always be on the train. Of course, the cause and the scene is very closely connected, so sometimes we just get updates through others. And we have many phone calls, everyday communication, when they have little problems. Our board also offered to help us in taking over a few of the projects, and they would keep contact with them. We also now have somebody working for us in Munich, it is a first step into a regional way of working. This helps us travel less when we try to keep contact with the initiatives. We are also considering opening other offices in Germany, at least another one in Berlin and one in Hamburg, in the medium term.

Is there anything that connects the initiatives you work with, with each other?

We ask all projects if they are interested in establishing a network among themselves and having an exchange with each other. We were very surprised when they said “oh, no”. We do have so many networks, not another one on top of them!” And it is puzzling, as the Miethäuser Syndikat, for instance, is just the opposite: it is a very grassroots, basic democratic organisation. People consider us in a more entrepreneurial context: they expect us to do the job for them, to be a service institution for them. But it also means that there is enough room for two very different organisations.

Do you see all these initiatives gradually upscale and grow into a parallel real-estate network?

I think we will be confronted with other questions. The Syndikat has a quite democratic structure and regional organisational structure. With us and with Stiftung Edith Maryon, I feel we need a more democratic structure. We already think about what happens if, let’s say, a project in Berlin fails and goes bankrupt. Who decides what would happen in the future on that building site: would it be only us, the Stiftung trias in Hattingen, or is it a matter for the Berlin projects as well. In the next years, we will have to take up this question and found a form of organisation to ask the neighbourhood projects, experts we know, and people even from the municipality, if they have ideas on how to reactivate a building or land following a failed project. They should make decisions with us. I think we must go this way, otherwise people will not accept the question of commons in connection with trias.

In a sense, you play a public role by providing space or finance for community initiatives; what is your relationship with the public sector that increasingly fails to play this role?

I think we established ourselves because of the example we set for others. It is one thing to talk about commons and talk about land-lease contracts, but there is a real difference when you do it. Because you convince people much easier, if you say “Look at the ExRotaprint, the Alte Schule Karlshorst, the Kunstwohnwerk in München.” It does convince politicians, universities, people from the co-housing field. The same with public administrations: for example, the Internationale Bauaustellung in Thüringen asked us for solutions for their organisation and development scheme. And that is happening elsewhere, too: the town of Metzingen, in Southern Germany, asked us to help them with a land lease contract to secure their buildings for centuries to be available for low-rent tenants only. Because in Germany one can erect a building and designate it for low-income tenants or people who can only pay, let’s say, 5-6 Euros per m2 for rent, and then one gets very interesting loans. But after twenty years this contract is over and then one can raise the rent up to market level. And for this mayor, this was not satisfying because twenty years is not long enough. She asked if we could do it in a different way, for a hundred years instead of twenty. We began to think about the land lease contract together. So we are on our way to become consultants also for the public sector. But we are too small to just to be consultants all over Germany and we do not really consider it as our main job, but it happens, and our publications, of course, are very often ordered by municipalities as well.

You have a safer method to preserve social inclusive projects than the public sector itself: they ask your help to secure buildings or land.

We do not consider the public sector as competitors: of course, we would like to see that piece of land in our foundation, because it gives us more possibilities in the economic field, but if a city supports a co-housing project by giving a favourable land-lease contract to them, that is fine and we are no longer needed. The problem is that people working in municipalities often do not have the right understanding of civic groups and I sometimes describe them as cold partners because they do not think in the same way. In the town halls, usually you find people with their small one-family building, driving a nice car and going to Mallorca for vacation, so having a very bourgeois life, and if you come there and say, we live as 40 people together in one house and we share things and so on, it is a question of understanding, and it sometimes makes cooperation difficult. But on the other hand, it is learning, bringing the ideas into the heads of people, who are far away from us, so I think it is a job as well. Sometimes I say our projects are like art, because people are standing in front of our houses and wonder why the hell they live that way. And it is like looking at art and asking what it tells me. This forces people into thinking.

We do not consider the public sector as competitors: of course, we would like to see that piece of land in our foundation, because it gives us more possibilities in the economic field, but if a city supports a co-housing project by giving a favourable land-lease contract to them, that is fine and we are no longer needed. The problem is that people working in municipalities often do not have the right understanding of civic groups and I sometimes describe them as cold partners because they do not think in the same way. In the town halls, usually you find people with their small one-family building, driving a nice car and going to Mallorca for vacation, so having a very bourgeois life, and if you come there and say, we live as 40 people together in one house and we share things and so on, it is a question of understanding, and it sometimes makes cooperation difficult. But on the other hand, it is learning, bringing the ideas into the heads of people, who are far away from us, so I think it is a job as well. Sometimes I say our projects are like art, because people are standing in front of our houses and wonder why the hell they live that way. And it is like looking at art and asking what it tells me. This forces people into thinking.

How could this work be upscaled onto a European scale?

It needs money and time. We are interested in the possibility of a Europe-wide platform, and meeting European partners. The problem is that the legal instruments in all our countries are very different: even between Germany, Switzerland and Austria, the land lease contract is quite different. This means that we cannot do the same just going over the border. It is hard work to have an exchange of knowledge and it is the way of thinking we must transport. It could be that our work in Germany is used to just explain how we do it, and then people have to translate it to their own countries, to their own possibilities within their limits. I realise that many projects and initiatives are in the situation we were in the 1990s: I hope we can help them with our model, showing the way we work. In Austria, there is a little foundation that is just being founded and they try to do the same job we do in Germany. We supported them with knowledge to help them doing it in the Austrian way. At the same time, we constantly have to learn from other countries, finding new questions, answers and knowledge that help us rethink certain standpoints. Gathering knowledge is an important part of our daily work. We must be in a permanent development stage, otherwise we will fail, I am quite sure; and as our work is atypical and not in the mainstream, we will always need to have more input.

Interview with Rolf Novy-Huy on 9 August 2016