When one borrower lost his wedding ring in a local park, he turned to an unlikely hero: a metal detector rented from his neighbourhood Library of Things. Incredibly, he found it. It’s just one of many small but powerful examples of how this growing social enterprise is helping people do more with less. Founded in South London in 2014, Library of Things now operates in 22 locations across the UK, with almost 40,000 members and over 70,400 rentals to date. For a few pounds, users can borrow household items—from drills to sewing machines—through self-service lockers in libraries, community centres and housing blocks. The aim? To make sharing easier than owning, cut down on unnecessary consumption, and promote a more sustainable, affordable way of living. In this interview, Library of Things Partnership Lead Ranjit Singh explains how the model works, how it’s funded, why councils and brands are getting involved, and how and why it could signal a shift in how we think about ownership, consumumption and the value of our resources.

Could you give me an overall introduction to the Library of Things and explain how the idea came about?

The Library of Things began in 2014 as a community project founded by three women who were frustrated by the waste they saw around them. Living in small apartments, they questioned why people needed to buy a drill they’d only use twice a year. They joined with friends and locals to set up a volunteer-run library of things in a shipping container in a South London car park, running it alongside full-time jobs out of a desire to help the planet.

By 2020, interest grew significantly across the UK and beyond. But replicating the volunteer model proved difficult—it relied on committed individuals and was affected by London’s transient population. They also found that donated tools varied in quality, causing operational problems. Managing different brands meant sourcing parts and training people was time-consuming, even for volunteers.

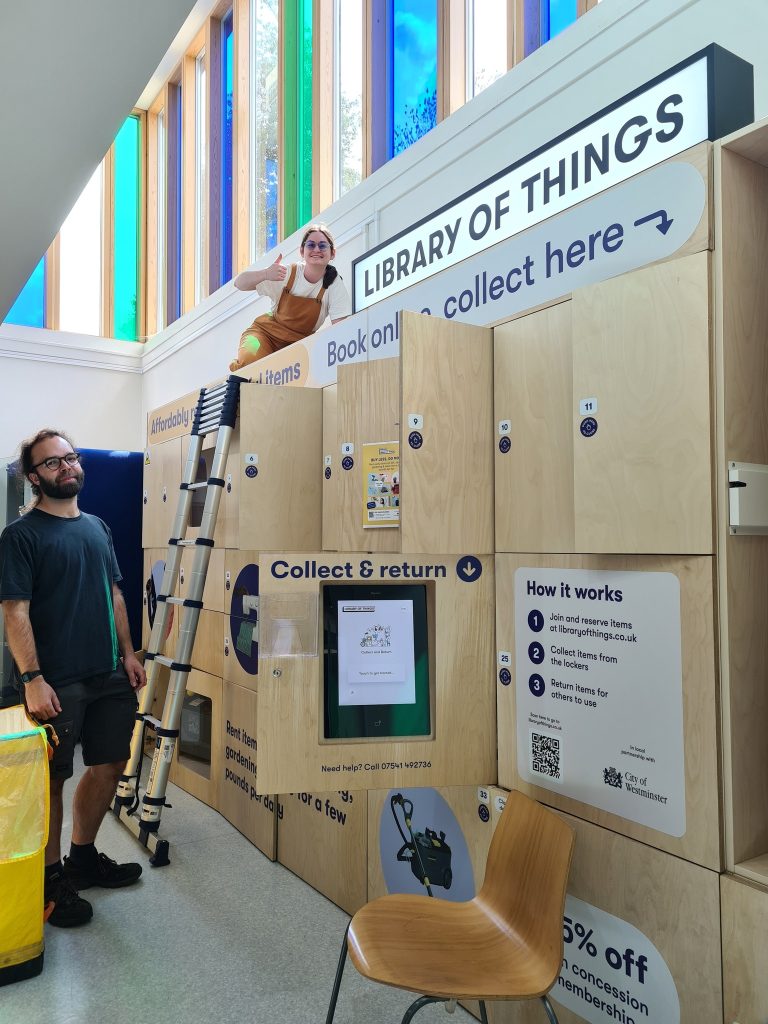

To address this, they moved to a self-service model in partnership with a local library, installing lockers stocked with new tools limited to two or three brands. This simplified maintenance and training. Since 2021, the project has expanded. When I joined four years ago, there were three sites; now there are 21 across public locations in London, one in a residential block, one in the north of England, and another in Barcelona. Both the northern and Barcelona locations are licensed operations using their own branding. They’ve purchased our software and paid for our expertise, as we know how to set up a Library of Things, promote it, and engage the community.

What kind of change are you trying to create? You mentioned that, for the three founders, the motivation was primarily environmental. Is that still the main mission?

Essentially, yes. The idea is rooted in behaviour change—what’s now called collaborative consumption. We can’t create mass change alone, so we work in partnership with municipalities and organisations. The bigger ambition is to build a coalition that can push governments to adopt legislation promoting reuse and repair. That means putting pressure on manufacturers to make things repairable. Right now, fixing a washing machine often costs more than buying a new one. But the EU’s Repair Directive is a sign of progress. We’re a small part of that ecosystem. Our mission is to make borrowing accessible to as many people as possible.

Can you tell me the typical user journey? How do people use your services?

It starts digitally. People visit our mobile-optimised website to browse our catalogue. One of our founders, Sophie Wyatt, is trained in user-led design, so the system is built with usability in mind. It supports a network of locations—users can either search by item or by location. The software shows real-time availability across sites.

Once users choose an item, they reserve it for as long as they need—one to four days typically. They can manage their booking directly, without contacting us. After payment, they receive a code via email and SMS. At the sharing station, they enter the code into a screen, the locker opens, and they collect the item. They confirm it’s in good condition, then close the locker. To return it, they repeat the process. We also send reminders and how-to videos by email and SMS. It’s high-tech but user-friendly.

You mentioned how much the Library of Things has grown in the past three years. Could you share some of the key figures and explain how membership works?

We now have almost 40,000 members, and the service’s been used nearly 60,000 times. The membership fee is around £2.50, a one-time fee for life. We’re looking at changing that and are running community consultations to understand what users are willing to pay. A high fee can discourage people at first, but once they see the value, they may be more willing to contribute.

Last year, we got a research grant to explore membership models. One idea is a supporter membership—someone not near a sharing station, maybe in Scotland where we don’t operate, but who believes in the mission and wants to support it.

The research gave valuable insights. In the next 12 months, we plan to introduce tiered options, including a low-cost membership for users on limited incomes, and options for those who can give more—like a pay-it-forward model covering someone else’s cost. We also have a 25% discount built into the software. If cost is a barrier, users tick a box and get the discount. No personal details or justification needed.

Do you have an estimate of how many items are available across all your locations?

On average, each of our sites has around 30 to 35 lockers. In those lockers, there are usually about 45 items. Some lockers contain multiple small items—like a laser measurer—and in other cases, we place two of something in the same locker, especially if it’s a popular item and they fit together, like two drills. People often ask us, “When users open the locker, don’t they just take both drills?” But they don’t. The system works on trust, and 99.9% of the users we deal with are very honest.

Can you tell me a little bit about who runs the Library of Things, and explain the organisational model?

Early on in our journey, our co-founders saw that the standard for-profit and non-profit models weren’t going to work for the mission-first organisation that we wanted to build. So we designed a mission-locked and ‘steward-owned’ business that was better suited – allowing flexibility of finance, and integrity and external accountability to the company’s values and mission.

Structurally we are a limited company with a clear social mission – practically this means our directors (including our co-founders) and impact investors are legally-bound by our founding documents to put our mission first in strategic decision-making. But we also designed a ‘mission lock’. This is in the form of one Guardian share, held by a non-profit asset-locked company – Things Trust.

This is made up of a group of mission guardians.These guardians represent three interests: the earth, the community, and the users. They are volunteers, and we meet with them quarterly to share updates. We also seek their advice, as each was selected for their specific skills and perspective. For example, one guardian runs her own business and is interested in promoting environmentally conscious behaviours in communities. Another comes from a finance background. One runs a Library of Things in the west—not affiliated with us, doesn’t use our software or resources, but shares our values and contributes through the stewardship role.

They can veto major decisions. If someone like Elon Musk wanted to buy the organisation and the internal team agreed, the guardians could block it. They function as a values-based safeguard, similar to a board, but focused on purpose, not profit. Ultimately, we hope to operate fully under a nonprofit structure. It’s an evolving form of governance, but the organisation has never been about profit. We’re a private company, but mission-led in everything we do.

Could you explain how the Library of Things is funded? You mentioned the membership fee and item rental income, but are there other sources that help you stay financially sustainable?

We’re funded through a mixture of sources. While membership fees are not currently a significant part of our revenue—they may become more substantial over time—we also receive income everytime someone rents an item. Our capital costs are typically funded by municipalities.

Municipalities commission us to deliver the lockers and supply all the rental items. They want us to operate the system and maintain the items, which includes employing the technicians. In return, we charge the municipality an ongoing service fee. So we’re not only the installers but also continue on as the long-term service providers.

You work with brands like Bosch, Kärcher, and Stihl. What do you think motivates manufacturers to take part in a sharing model like this—and what benefits does it bring to the Library of Things?

We use Bosch for many DIY tools, Kärcher for cleaning equipment, and Stihl for gardening tools. These companies have traditionally sold products—but they’re also citizens of the world, and human beings like the rest of us. I think they’re genuinely trying to navigate the shift from a consumption model to sharing, because they recognise they need to be part of that ecosystem.

We have a lot of conversations with Bosch, Stihl, and Kärcher, and they’re learning from us. We share user feedback—what they say about the tools, how they use them—which helps improve the products technically. It’s also valuable for marketing. It lets users touch and feel the products, build familiarity and trust. For the manufacturers, it’s a chance to develop a deeper relationship with users—not just through advertising, but through hands-on experience.

They are commercial companies, and I think this shift creates real tension. On one side, sales teams are focused on selling more product. On the other, sustainability teams are committed to environmental goals, and now the EU’s Repair Directive will force re-engineering in how they operate. They’re still early in that transition. So yes, we need to be patient—but also hold them accountable. These companies are part of the same world and share the responsibility to help meet our sustainability targets.

How many of your locations use self-serve lockers, and how many operate in public spaces or other community settings without lockers?

In London, all of our locations use lockers. They’re situated in public libraries, shopping centres, community venues, and one is even in a private residential block. So while they’re all self-serve locker models, they’re still hosted within public or semi-public community spaces.

A couple of years ago, we ran a pilot in Brighton—funded through the Interreg EU fund—that didn’t involve lockers. It was based in a reuse electrical shop. People would use the same software, receive a six-digit code, take it to the shop, and someone would collect the item from the stockroom and hand it over. That same model is now running in Wales, where we licensed our software to a local group. They’re open two days a week and offer manual pickup using our platform.

We’re seeing growing demand from community groups who don’t want the locker system but are very interested in using our software. Just this week, we signed on another group like that. Now that we’ve proven the model works in Wales, we expect many more to follow. We really want to encourage this. We’re not aiming to be the Amazon of sharing stations. If there are 10,000 sharing libraries out there, and we’re directly running 50 or 60, that’s exactly what we want.

Many of your locations are based in public spaces like libraries or community centres as you said. Beyond tool sharing, what role does community connection and social interaction play in your model?

That journey starts long before a sharing station opens. We always encourage our municipal partners to begin community engagement early. Some are more resourced than others, but those that can often organise webinars or consultations—even without us. We sometimes suggest they don’t mention Library of Things at all. Interestingly, in nearly every consultation, someone will say, “We’d love a Library of Things here.”

Once interest is confirmed, we collaborate with the municipality in organising a follow-up meeting or webinar where we explain our ethos and mission, and then invite questions from members of the community. If the municipality and community want to proceed, we work with them to build a database of local community and environmental groups. Often, we’ve already been contacted by some of them. In our experience, this engagement process supports the long-term viability of the project and ensures the service becomes a highly valued commuity asset.

We also have a “wish listing” tool. We ask groups to send it to their communities to learn what people want to borrow. Once we launch, we invite those groups to the opening and keep them involved. So community engagement is built in from the start. One thing we’d like to do more of—when funding allows—is skill-sharing workshops. We’ve tried different formats, but to do it well, you need a great teacher, good space, and proper equipment. A sewing workshop needs ten machines. We can’t just pull those from lockers and drive them around, so we rent them, buy materials, and book a venue. It’s resource-heavy.

When supported by municipalities or funders, we run these workshops. But what communities tell us is they want more than one or two workshops—they want a series. If the first sewing session is sewing on a button, the tenth should be making a jacket. It’s the same with DIY. People want a course, not a one-off. We’ve spoken to local authorities about embedding this kind of upskilling into adult learning—ideally before we arrive—so repair and reuse become part of community learning and reach people who might not usually engage.

Also, when people borrow items, we include links to videos on how to use them. Some are ours, some from manufacturers—but those often focus more on the brand than practical skills. So we create our own PDFs and wikis for more hands-on, accessible support.

With the skill-sharing courses you mentioned—especially longer-term ones—do you see a future where a municipality might fully fund and organise them?

We’re still figuring it out. It doesn’t have to be us delivering the workshops. There are already strong volunteer-led groups doing this work. For example, Hackney Fixers and West London Fixers are both active. There’s also the Restart Project—they’ve started two fixing factories in London.

These are all non-profits looking for funding to expand, and they offer free repairs. So, there are many actors already. What we hope is that the government recognises the value of what these organisations do, because it contributes to community resilience. In London, the government is now allocating significant funding toward retrofitting old housing. The question is how to align that investment with community skills—helping people learn to repair, reuse, or support retrofitting themselves.

Do you see borrowing as a gateway to deeper behaviour change? Is sharing becoming more common in the UK? And do you have any insights into who your users are and what motivates them?

Yes, borrowing is definitely a gateway to broader behaviour change, and we’re seeing the sharing trend grow across the UK. Many groups have started their own libraries of things, independently of us. Our latest impact survey with almost 600 members showed that after using our service, people reported reusing more, repairing more, recycling more, buying fewer things and feeling more connected to their community. We’d love to secure funding for a deeper research project. We’re currently in conversation with partners across Europe about joining a continent-wide user research initiative—possibly involving other Libraries of Things, brands, and institutions. Even though the UK is no longer in the EU, we’re hopeful that there are still ways we can participate.

Do you work closely with other organisations in the repair and reuse space, and is there potential to collaborate on wider advocacy efforts?

We’re friendly with all of them. We have a close relationship with Restart, and we’ve had conversations with others like Hackney Fixers and West London Fixers. Many of our technicians—who are in paid roles—also volunteer with these fixing groups in their spare time. There’s a real ecosystem growing in this area

We’re hoping that the government recognises the value of all these organisations. They’re helping to build community resilience, which is increasingly important. For example, in London, the government is allocating significant funds to retrofitting old housing, and there’s a real opportunity to align that with giving communities the skills to contribute directly to that work.

Is there a broader European network for organisations like yours?

Yes, there is. It was initiated by Bax and was originally called the Digital Kiosk Network. That network started about two years ago and has since changed its name to the Access Economy Alliance. We felt that “kiosk” was too narrow a term, since there are many different kinds of access behaviours—whether it’s accessing mobility services or borrowing a drill. It’s really about accessing products rather than buying them.

Can you share a few examples of what members have borrowed and how they’ve used those items—any memorable or surprising stories?

One of the stories that got the most traction was about someone who lost their wedding ring in a park over the weekend. They realised their local Library of Things had a metal detector, so they borrowed it, went to the park, and actually found the ring. It was a big park, too, so it was a pretty remarkable outcome. We also hear a lot of great stories from communities that come together to improve their streets. It’s not just gardening—it’s things like cleaning and general upkeep. For that kind of work, they’ll borrow items like high-pressure water cleaners and strimmers to tidy up hedges and green areas. There are lots of stories like these on our Instagram feed. It gives a really good flavour of how people are using the service to do small but meaningful things in their communities.

Interview by Sophie Bod.

Read more articles about the sharing economy: