“If you have space, you should do something directly for the people who make up the area.”

ExRotaprint was founded in 2007 by tenants of the Rotaprint industrial complex in Wedding, a traditional working class district in Northwest Berlin. When the complex was put up for sale by the Berlin Municipality’s Real Estate Fund, members of the ExRotaprint began to look into the possibility of buying the area. Teaming up with two anti-speculation foundations, the tenants’ non-profit company became owner of the 10,000 m2 complex, setting a precedent in Berlin that inspired many experiments in cooperative ownership, and a campaign to change the city’s privatisation policy.

How would you describe the area where you established ExRotaprint?

The Rotaprint Company used to be well known for their offset printing machines. The Rotaprint manufacturing site was located in Berlin-Wedding for more than 80 years, and the company shaped the area in the long term. Apart from the expanded premises they even had a guesthouse in the next street and a workers’ holiday home in Berlin-Wannsee. We felt that the spirit of Rotaprint was still here, which is why we named the compound ExRotaprint. It is also to honour the architectural achievement, because we think they left fantastic buildings.

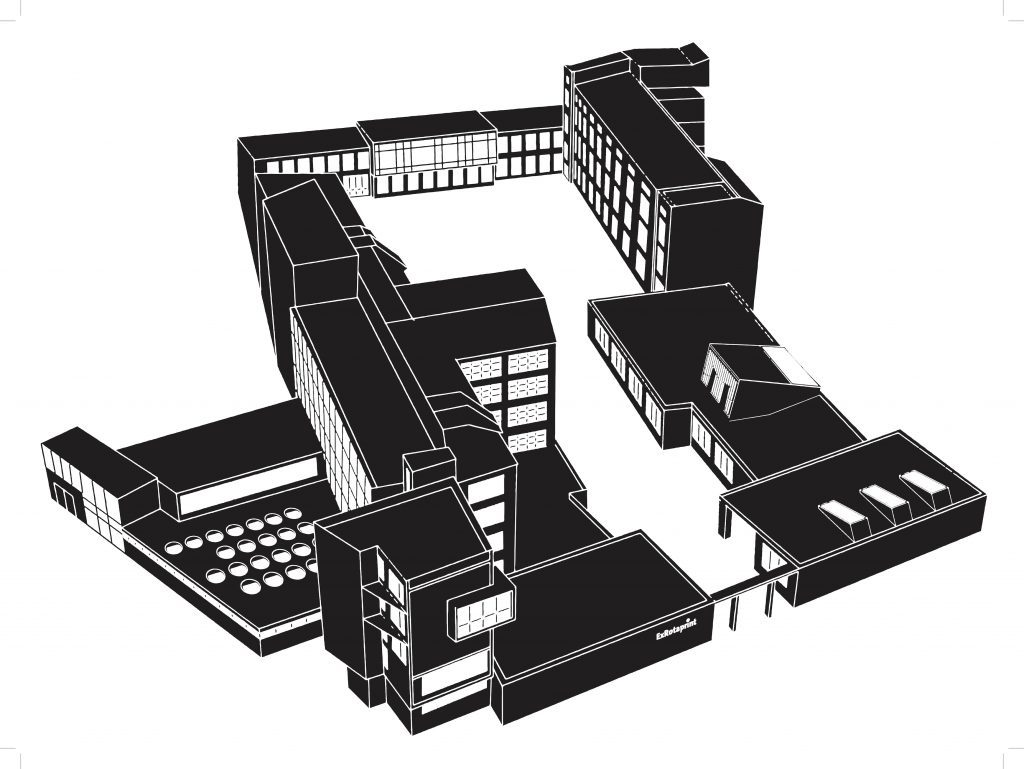

The complex was largely destroyed during the Second World War; the reconstruction took place in the post-war years and Rotaprint hired architect Klaus Kirsten to design the new buildings. They all reflect the post-war modernist style of the late 1950s. The concrete tower building at the corner, built in 1958, became a kind of a sign for our project. It is visible from the street, and there is nothing similar in Berlin. With its rough façade and cubic shape, it represents a very untypical style for this city. It was not meant to be a brutalist building, it is simply unfinished. We found out that the architect’s plan was to add two more stories and then to have a final façade – probably plaster – but that never happened. It is already a special story that the building has been listed as a monument the way it rather happened to be. We like the idea that something can be very good which is unfinished. We always use this kind of interpretation also for the way we work with ExRotaprint.

Did the status of a listed monument create any difficulties for you?

The entire Rotaprint compound is a listed monument since 1991, and this status is what probably saved the buildings from demolition. From our perspective, this was the best thing that could happen, and the official status of being listed as a monument is still positive for our project. A lot of people are afraid of this status because you have to find agreements with the authority on what you do and what to change. Mainly, we wanted to keep it as it is. We do the renovations on the compound step by step, and the renovations we take on are based on the needs of the buildings. The architecture was and still is an important aspect and a motivation for the ExRotaprint project. We want to keep its visual appearance as best as possible. Now that Wedding is not completely out of focus anymore, people wander around here, taking photographs.

How did you get involved in rethinking the complex?

From 2000 on, we were tenants in one of the former Rotaprint buildings, at the time owned by the City of Berlin, when they put it up for sale. In 2002 the City of Berlin decided to change its real estate policy and put all the properties it owned but did not need for its own uses up for sale: this was a policy to fill the empty pockets of an indebted municipality. Looking back, this policy obviously changed Berlin a lot. The only criterion for selling buildings was the highest bid, the highest amount of money, and no criteria of urban development or social and cultural concepts were taken into account. We were confronted with this new policy right at its introduction, and we knew that we had to do something instead of waiting for the investor who would finally buy the buildings and push us out. At the time investors were all over the place in Berlin, but the Wedding district, a former working class district, was not yet attractive for them. This gave us a timeframe to develop our concept without much competition.

How did you organise yourself?

At the very beginning, we took photographs of the workshops and everything that was already on the compound. We also made interviews with the people about how much they had already invested in their space, what they were doing, if they had employees etc. In the end, we had a little folder presenting the idea of keeping the local structure, taking it as a starting point and promoting and expanding it. Then, we started the ExRotaprint project with the people who were already renters on site, a very heterogeneous group. Only half of the compound was rented out, quite some empty space was still available. The first step was to involve others on the compound in the idea of organising ourselves. At the time, people did not know each other despite working within one complex; it was a very anonymous space. We decided to found the association of tenants at the former Rotaprint premises: the association was called ExRotaprint. This was in 2005, and it was our first platform. Step by step, we educated ourselves and became project developers. At the same time we took up negotiations with the city about the purchase price.

How did these negotiations go?

After we founded the association we arranged an appointment with the officials from the Liegenschaftsfonds, the city-owned company that was in charge of selling publicly owned land. The Liegenschaftsfonds had the task to fill the city’s empty pockets by selling off properties. Today this policy is considered to be a mistake because there is a new need for housing but the city will never get back the land sold. Our community-based project development concept was of no interest for them. Unfortunately, our negotiations did not go anywhere. In the meanwhile, the Liegenschaftsfonds worked behind our back to involve an Icelandic investor who was willing to buy 45 properties at once, and the Rotaprint site became part of that package. This was just the opposite of our idea of local development for the area, and it took us one and a half years to fight against the investor. In the end, he did not buy anything and the Liegenschaftsfonds called us again and said: “Now make another bid, please.” Luckily, we knew that as a part of the package, the Icelandic investor would have paid only 600,000 euros. We simply offered 600,000 euros as well, which was nothing for the premises, but under the political pressure we organised they accepted it.

How did the tenants conceive the possibility of buying the property?

We had substantial as well as controversial discussions among the tenants and in the association. People are very different, and as different were their ideas about how to deal with the property. Someone said, “I have some friends who can give us the money.” This was a big warning for us because whoever brings the money in, decides in the end. Most artists said, “This is very interesting but I have no money at all.” Others thought that we should set up a cooperative. A social worker who worked with unemployed people said, “We cannot sign anything in conflict with politics because our projects are funded by politics.” Everybody had a different situation, a different perspective and different individual interests.

The most difficult thing was money: none of us really had any. We were facing a 10,000 m2 complex and we needed an overall solution. We could only buy everything together; it was not possible to buy just this or that workshop. We also knew that some of the buildings only needed a little bit of maintenance while others need a significant amount of money to be invested for extensive renovations. We knew that it would not work out if people only think about their own units. To buy the premises was one hurdle, but renovation costs would be even much higher. There was a kind of pragmatism rising among the group. People were concerned that it would take 25 or 30 years to pay the investment back and by that time they would be old and their businesses might not exist anymore.

How did tenants relate to the idea of becoming owners themselves?

As soon as the idea of buying the Rotaprint area emerged, the thought of owning the compound in any kind of constellation was immediately connected to the idea of profit. We realised that in the future, when the compound is renovated, its value would increase immensely. While we were able to buy it for 600,000 euros in 2007, we could already predict that in 5 or 10 years, the compound would be worth ten times more. Right at the beginning, even before the project really had started, the idea of personal profit, of individual investment return became a huge threat for the project. The danger was that the group falls apart because of individual interests. At that point we decided to think about a non-profit limited company in order to exclude the possibility of individual profit and speculation, and to ensure that we will never have the same problem again with the compound being sold.

We would have been able to buy the compound privately, nobody forced us to come up with a non-profit solution. The Liegenschaftsfonds did not care, they did not expect a locally sustainable development. But it was important for us to show that a new and different way of dealing with property is possible, and to make sure that the people who made up the district could continue to use the space. Finally, ExRotaprint became reality as an open and inclusive project development that finances itself and does not rely on external funding.

Most of the members of the association became partners in the non-profit company ExRotaprint. We had to collect some money among the partners to set up the company, for legal costs and to bridge the time until we could rely on the rental income. Some members questioned the idea of a non-profit company as they were business people, such as this old-fashioned electrician who had always lived and worked in the district. We thought that people like him have to stay here and remain part of the project, although he does not play an active part. Some people stepped out, while others showed interest in the project and joined. In the end, we all remained renters on the compound, regardless of being a partner in the company and active in the project or not.

How did you manage to raise money to pay the purchase price?

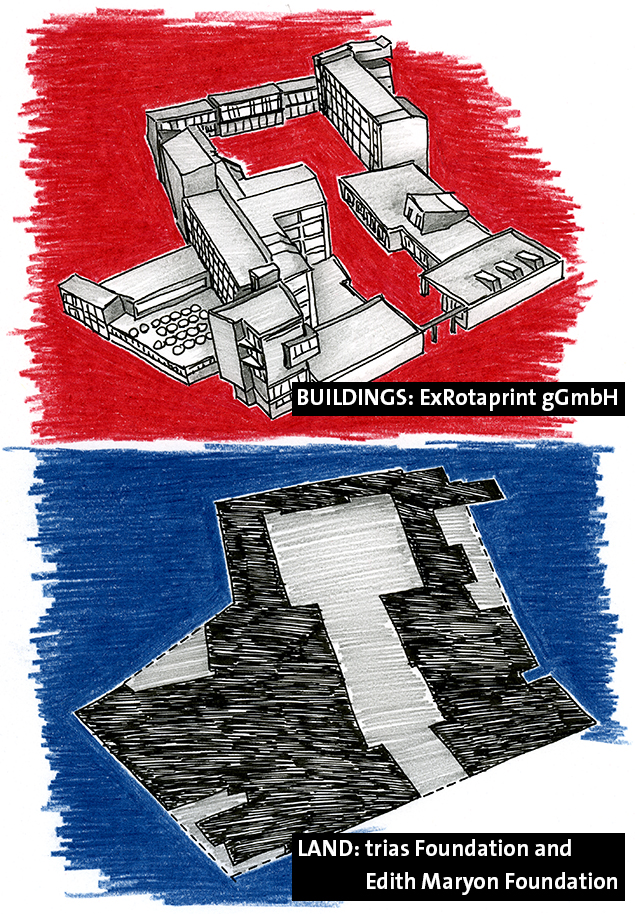

Our negotiations with the Liegenschaftsfonds on the purchase of the compound were concluded when we brought in the two foundations, Stiftung trias and Stiftung Edith Maryon. Both foundations have similar agendas to prevent speculation with land, and to install alternative models that take land completely off the market in a way that it could never be sold again. This was a very convincing concept to us. On the other hand, tenants founding a non-profit company for project development and, never the less, the cheap purchase were convincing to the foundations.

When we began to negotiate with Stiftung trias, the foundation was still quite small and they were not able to pay the entire purchase price of 640,000 euros (including acquisition costs). In the end, they brought in Stiftung Edith Maryon, and together they shared the sum. We signed a long-term land lease (heritable building right) contract for 99 years with them and agreed on paying a 5,5% annual interest rate. The purchase price was so low that the 5,5% does not create difficulties for us. Today ExRotaprint even pays 10% of the net rental income to the foundations, making it a 6% investment return on the purchase price. It is a business relationship, not sponsoring. In the long run, ExRotaprint contributes to the financial means of the foundations.

Image (c) ExRotaprint

Why did you need the heritable building right contract?

The heritable building right is a kind of long-term lease. The instrument was established in Germany more than 100 years ago to lease land to cooperatives to build affordable housing or to enable poor families to build a house. Instead of buying the land in the beginning, which would necessitate a lot of capital, they pay an annual interest or lease fee. This fee is not paid off within 25-30 years, like a mortgage to a bank, but permanently, for 99 years to the landowner. In our case, instead of paying a mortgage, we pay the fee to foundations that use their revenue to move further land off speculation.

The heritable building right is a legal instrument that separates the land from the buildings and thus splits ownership. ExRotaprint gGmbH owns the buildings, and the foundations own the land. This secures the land from being sold again because to exclude selling of land is the very reason of existence of these foundations. Our objectives for the project and its development—the renting of equal space for “work, art, and community,” the project’s socially integrative nature, and its non-profit status—were formalised in the heritable building right contract which makes them obligatory for the duration of the contract.

How did you start the process of renovations?

When we took over the premises, the outer shells of the buildings were in a very bad shape. Step by step we renovated the facades, roofs and windows. From the perspective of the renters, the most important thing is to keep the rents low, so the whole calculation of the renovations is different from an investor’s perspective. It is based on what is really needed. It is very important that the project is directed completely from the viewpoint of the renters. All aspects, like the amount and the kind of construction works that we are doing, and how far the renovation goes, are decided by the people who are on-site. For example, we kept all the metal windows from the 1950s, which is much cheaper than replacing them – and they look cooler… In the interior, we only made improvement based on fire safety regulations, and fixed the water and heating supplies when necessary. Further improvements inside the units are organised mostly by the tenants in the way they want it to be.

When we took over the compound and signed the contracts, we made a calculation for the minimum amount of renovations that we would have to do. We estimated the costs to be under 500,000 euros, but we knew that we would need to have a complete overview of our revenues to calculate how much money we would be able to invest. In the end, in 2009, we took out a mortgage of 2.3 million euros, and we also permanently reinvested the surplus from rental income for the renovations. Today, we calculate that we will spend altogether around 4.2 million euros for the restoration of the compound. We took out the building mortgage from the CoOpera Sammelstiftung PUK, a Swiss pension trust that invests its pension payments mainly in sustainable real estate projects. We pay an interest rate of 4%. For a normal bank in 2009, ExRotaprint would have been a high-risk project. CoOpera met us and said, “For us, meeting you and seeing your determination to ensure this project gets through is the best guarantee.”

How does ExRotaprint as a non-profit company and association function today?

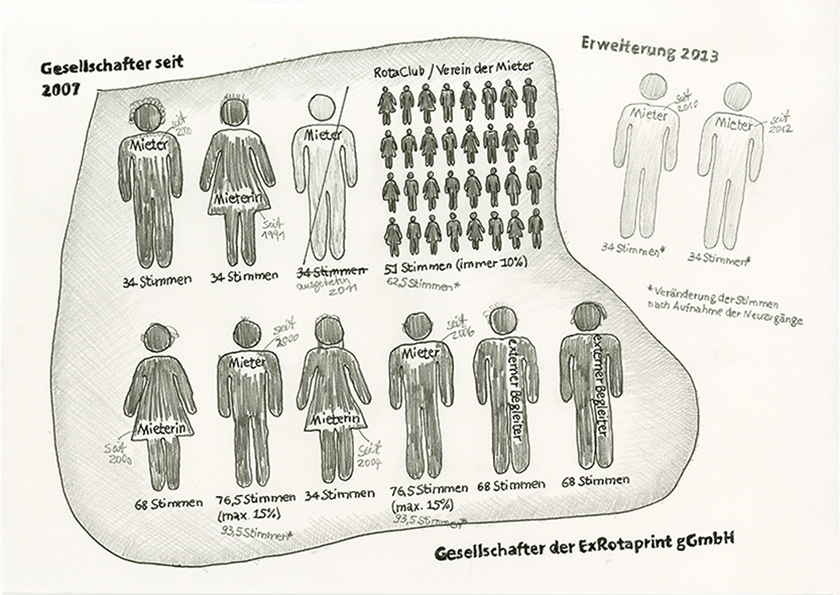

The ExRotaprint gGmbH company has ten partners. We are all renters and we also have the association of all renters, the RotaClub e.V. (which was formerly the ExRotaprint e.V. as the first platform) as the eleventh partner. The partners and the board of the association meet once a month. The planning team consists of 4 people and meets once a week (the two architects Oliver Clemens and Bernhard Hummel and us). Work is paid, although it is not a well-paid job. Our financial construction relies completely on the income from rents. The official status of a non-profit company goes along with the obligation to invest our gains in declared non-profit goals. ExRotaprint gGmbH has the goals of supporting monument conservation and arts and culture. This enables us to maintain the listed heritage buildings on the compound, and prevents the project from divesting the capital outflow into private pockets.

Who are your tenants?

We rent spaces for various uses; we wanted to have a heterogeneous group of renters here, and not only the creative class, which is what usually happens in Berlin and other places. We have this fantastic architecture, a very inspiring place, but we think it should not be for the sole use of artists and creatives alone. From the very outset, we had the idea for the ExRotaprint project to do something that makes sense to people that live in the neighbourhood. In the beginning, we decided that we were going to have community outreach projects and normal workers at ExRotaprint. Workspaces and production unites that give regular jobs to people. The whole compound is a mixture: one third of the available space is for arts and culture, one third is for social projects, and one third is for production and regular work. We have local businesses working, we have art studios and graphic designers, and many community outreach organisations, such as German classes and services for the unemployed, that are of great need here in the Wedding district. About 200 people come to ExRotaprint every day to learn German. We also have a school that works with dropout teenagers who left school or who already have a criminal record, a typical phenomenon in the area. This school is their last chance to return to a social consensus, and next door or on the street they see their buddies who do not have this choice. If you have space, you should do something directly for the people who constitute the area.

How do different tenants coexist on the site?

The way how people act is very different and depends on their social background. The client of a social institution that supports unemployed people, can be seen in a way similar to an artist who is in a comparable financial situation but self-employed. It is just the opportunities and the self-perception that are different. We think it is essential for diverse realities and identities to come together in the same location. People from Bulgaria or Romania in German classes are next to entrepreneurs, designers and workers – they are not separated. The chance of interaction, or at least of notice exists. That makes the city more open for needs and realities. Running a project from the perspective of the locals is almost like curating. We permanently look at what makes sense here and today. With our utilisation concept there is a higher need for moderation to find solutions and understanding.

What is your long-term goal with ExRotaprint?

The obvious objective is to consolidate the buildings for the next at least 30 years. ExRotaprint will stay an open space for the people in Wedding and their needs and occupations. With what they do and produce at ExRotaprint, they generate the important social, economic and cultural capital.

The city of Berlin has changed a lot in the past decade. The free and easy accessibility of space with low rent in Berlin came to an end, the city is “normalising”; it is becoming a regular capital with fast raising land prices. Today ExRotaprint functions as an example for successful community development. That makes it easier to start similar non-profit – and hopefully diverse – projects in the city. We interfere on different levels politically to spread our ideas of an open city with chances for all inhabitants.

Interview with Daniela Brahm and Les Schliesser on 15 August 2014, 30 October 2014 and 8 April 2016

This interview is an excerpt from the book Funding the Cooperative City: Community Finance and the Economy of Civic Spaces