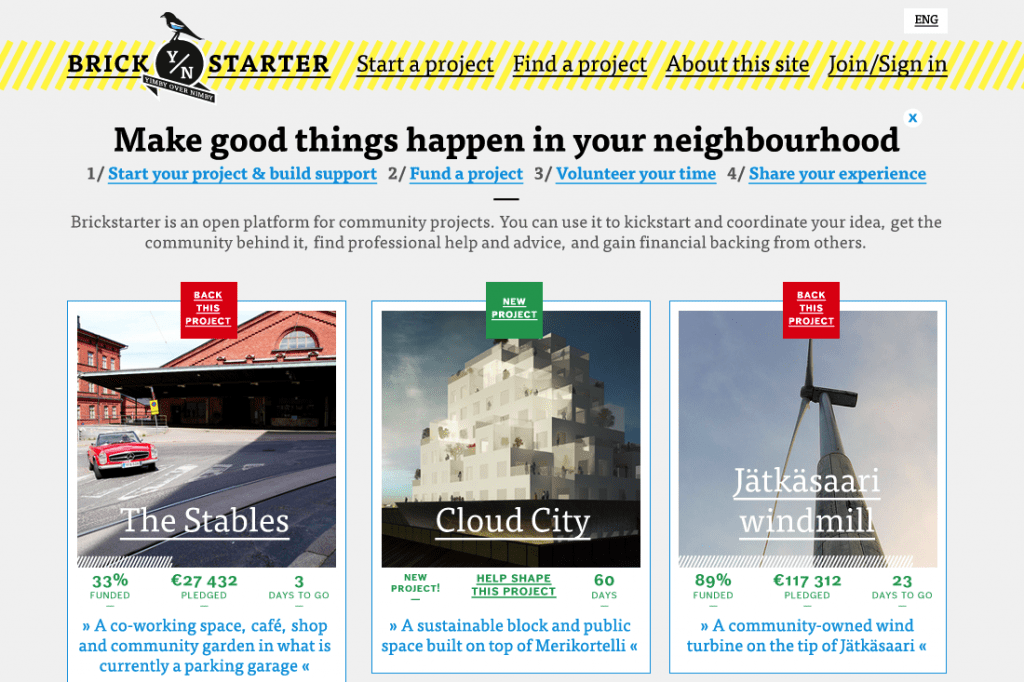

Brickstarter is a platform for crowdfunding and crowdsourcing architectural projects, initiated by Bryan Boyer and Dan Hill, and realised within the Finnish Innovation Fund, Sitra. Brickstarter was conceived as an experiment to test the possibilities of opening the design and development of urban environments, to reduce the opacity of urban development processes and to create communication between various urban stakeholders. At the time of the launch of its combined research and prototype in 2012, Brickstarter generated passionate debates about the role and possibilities of crowdfunding in urban service provision, and its relationship with traditional public infrastructure funding.

“We were looking at using crowdfunding as a way to effectively vote with your tax dollars”

This interview is an excerpt from the book Funding the Cooperative City: Community Finance and the Economy of Civic Spaces

What gave birth to the idea of Brickstarter?

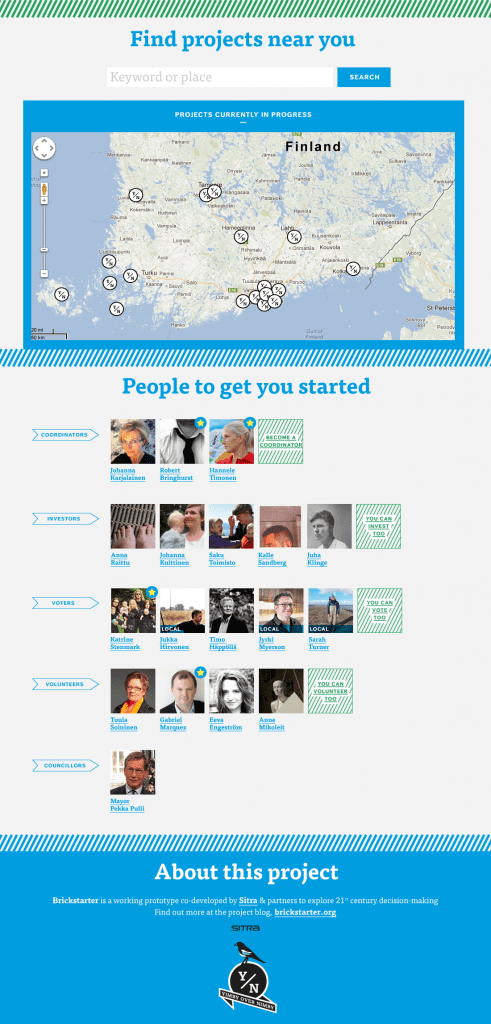

Brickstarter began at the intersection of a couple of threads, but it was primarily a recognition that an increasing number of people had a desire to be involved in shaping the city, and that a growing number of platforms were emerging that were experimenting with crowdfunding and crowdsourcing. We saw an opportunity to find a way to test those out in the built environment. So we began Brickstarter really as a provocation. We did do some experiments with a small city in Finland. But the bulk of the work was in exploring the issues related to taking a crowd-funding model and using it in the built environment. The big motivation for us was to try to expose some of the difficulties in that translation: we were concerned that taking a system that works well for products and projecting it directly onto the questions of building or city making would expose a number of potential issues or pitfalls, and we wanted to get ahead of those.

What issues were you precisely looking at?

We were looking at the limits of crowdfunding. What is appropriate, what is likely, what is plausible? An important aspect attached to this is the fact that a piece of architecture necessarily, or let’s say, in 99 percent of the cases, exists in one place. Which means that the people who are capable of, or likely to fund it, probably also exist in close proximity to the location where the building is meant to be. Also, if you are lucky enough to be in a city like London, New York or Tokyo, with a sizeable population in its own right and capable of drawing a significant number of people for business travel and tourism, you can imagine that a project in such a city could attract enough attention by people who live there, or hope to live there, to conceivably attract funding. But what about Manchester or San Jose, California or any one of a number of cities that are large in size, but not megacities.It then immediately becomes more questionable that you have a large enough population to draw from in the first place to obtain a small percentage of which, end up contributing to any given project. So the scale question is not so much the scale of the buildings – it is the scale of the funds. And finding a way to attract enough funds to actually pay for an entire construction project is no easy feat, regardless of how you are funding it.

Does the scale of a crowdfundable building also correspond to its level of complexity?

The question about complexity was actually the more important discovery in the Brickstarter work. On that issue, what we found is that the financial costs of building something new and interesting in the city are in reality, probably not the most significant element. The more difficult aspect is that there is an opacity to the process of getting something new built. So when you look at the example of the Kulttuurisauna, which is a project in Helsinki that we spent some time analysing, they were doing something that had never been done in exactly that way before in Helsinki. It was because of that, that it was an exploratory process both for the architect/client, (in this case, a couple who played both roles) as well as for the city. Both sides were exploring the implications of this idea and how to make it happen. Midway through the project, the city reversed an earlier decision and this team suddenly found themselves being required to switch from a simple foundation to pylons, which required a significant investment to pay for. The city demanded the more expensive pylons be installed, and this decision came after it was too late to turn back.

Through processes like this, we were finding that even if you have a mechanism to gather those funds, the bigger issue is that it is very difficult at the outset to predict what you will likely have to deal with, what you are going to need to pay for, and how long that process is going take. The bureaucracy and opacity of such systems that architecture and buildings have to participate in or have to be processed by, just makes it incredibly difficult – if not impossible – to predict everything in advance.

And so ultimately, one of the issues that Brickstarter was pressing was, how do we remove some of the opacity of these systems, and by doing so, drop the cost of development. Which is kind of the inverse, actually, of crowdfunding. Crowdfunding is to say, “ok, let’s find a way to gather up what money we have and throw it at a problem!” We can do that, and that was certainly an interest in the project, but there was a flip side as well, to say: “how do we engage directly with the machinery of government and find a way to reduce the hidden costs that are implied by the way that we currently structure decision making?”

How can crowdfunding complement traditional public funding?

Even in Helsinki, the capital of Finland, the population is relatively small, at around eight hundred thousand. When you go to the second largest city in Finland, you immediately have a much smaller population with even more limited funding possibilities, so this implies that leaving it purely to the market will only work in particular places with larger populations. Smaller cities need to look for ways to invite the will of the crowd, but multiply, leverage, or augment their individual resources.

We were looking at using crowdfunding as a way to effectively vote by allocating some portion of your tax dollars: is there a way for a platform that is run by a municipality or potentially by a central government, to be used as a participatory budgeting mechanism to give people a means to have a more direct impact on the way that a portion of their tax money is being utilised or distributed? If you imagine something like that happening, it can slot very well into existing structures of open competitions, it might even actually increase the attention such competitions get because now people will have more of a direct vested interest in their outcomes. It is something that goes back to the question of how we engage with the machinery itself, with the mechanisms of decision-making and ultimately give ourselves as a population or as a citizenry the courage to experiment with that.

What about connections with private or corporate funding?

When thinking about how crowdfunding could work compatibly with private funding, one of our starting points was an observation. My neighbourhood in Helsinki, Punavuori, had a tremendous amount of hair salons for some reason. The space on the ground floor of my apartment building was previously some kind of a store and one day it became empty. It sat there for a little while, and I found myself in a position where I wanted to send a message to all of the potential occupants of that space, anybody who could take it over for development. I wanted to give them feedback about what I wanted to see in the neighbourhood. And by extension, it is an interesting question to imagine would happen if all of us had a way to express what we wanted to see in our neighbourhood?

Of course, there is some personal satisfaction that comes out of the ability to say “I don’t want another hair salon, I want a bar!” or something like that, but it also brings up this possibility of giving feedback to people who are in a position to take a financial risk. Imagine that you are McDonald’s and you are considering opening a new location. You have resources to pay for analytics and research about the demographics of that area, about the real estate trends, about your competitive landscape – and you can get to some degree of certainty as to whether it is a good investment of your time and money or not to open a store at a given location. By contrast, if you are a local business, it is very likely that you don’t have access to the kinds of resources needed to do the same research. And so, if we have a platform that allows people to express their desires for the city around them, it becomes an interesting opportunity to level the playing field between a mega-developer or corporation and actors on a much smaller scale.

Of course, what I’m describing now is a very quick and naïve interpretation, there are all sorts of complexities to it and opportunities for capture by large interests. But again, I think it points to the necessity of finding ways to experiment here, because the deck is already stacked against the small and interesting initiatives and developments in cities. The complexity of developing anything in the city means that large actors are the ones who have an advantage because they have more ‘fat.’ They have more money in the coffers and it helps them weather the ups and downs the process. Anything, in my view, that we can do to make it easier or cheaper or more plausible for smaller entities to propose and literally build parts of the city is a positive outcome.

Interview with Bryan Boyer on 12 August 2014