Hidden behind gates in Budapest’s crowded streets, community gardens are quietly demonstrating alternative ways of living in the city, offering a chance to slow down, develop reciprocal relationships with nature, and build genuine community ties. This research-based article examines how these gardens function as restorative spaces, learning environments, and neighborhood connectors, while also addressing the challenges of access and inclusion in urban gardening initiatives.

Gardens as living laboratories

Walking through Budapest’s crowded streets, squeezed between parking lots and apartment blocks, one will occasionally find gates swinging open to reveal patches of cultivated lands: community gardens. They aren’t perfectly manicured spaces—rather, imperfect experiments where sometimes plans go sideways. But perhaps that’s what makes them such scalable spaces for relational learning, embedded within the urban fabric.

While many of us initially perceive these gardens simply as places for growing food or making neighbourhoods greener, they reveal themselves to be more. Amongst the compost bins and raised beds, people not only engage in horticultural experiments, but also in learning and unlearning: how to relate to ourselves, to one another, and to the intricate living cycles around us.

Driven by curiosity about how these gardens are lived and felt, we sought to understand these spaces as living laboratories where unexpected ties are formed between the act of tending living things, the formation of communities, and a deeper sense of belonging to the city.

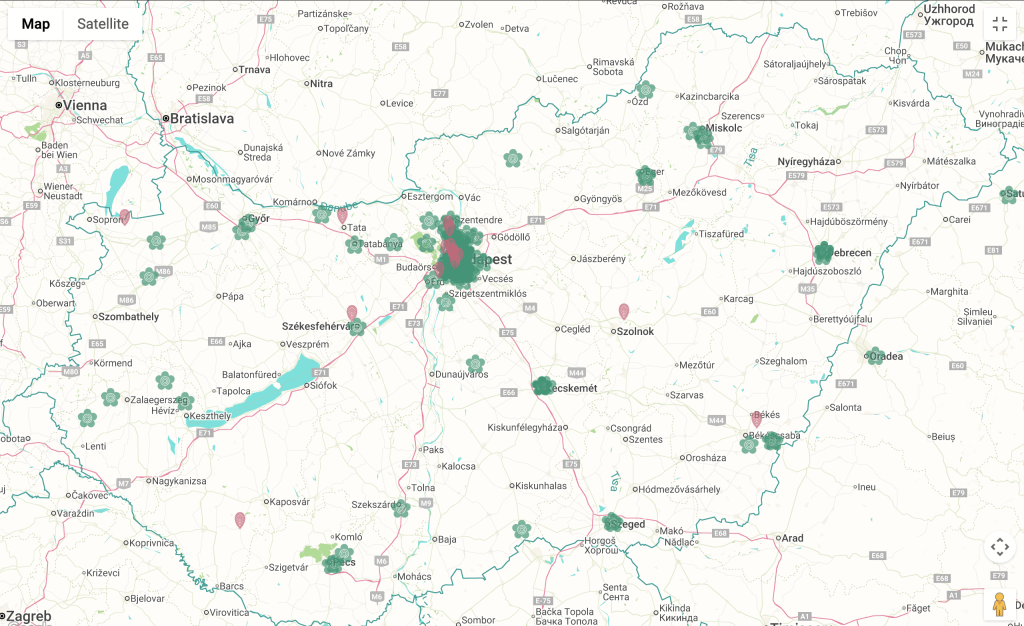

Through conversations with nine local gardeners across different community gardens in Budapest, a tapestry of personal stories, frustrations, and insights into what these spaces make possible. No two gardens were alike, differing significantly in size, underlying philosophy, and their specific urban context. The people we spoke with came from different backgrounds and had different reasons for being there. Therefore, the insights presented here should be understood as fragments contributing to a broader, more complex picture of community gardening in the city. All the quotes here are anonymous to protect people’s privacy.

What emerged from these conversations was far from a singular narrative. Instead, we uncovered a landscape of contrasts, a reflection of an often-overstimulated city life. The gardeners’ voices revealed that simply being in the garden creates numerous avenues for learning, and crucially, sometimes for letting go of control and trusting nature’s rhythms rather than attempting to micromanage every detail.

A Sanctuary from Overwhelm, Disconnection, and a Lost Sense of Agency

For many community gardeners in Budapest, their plot is more than just a green space—it functions as a vital refuge from the relentless overstimulation and isolation so prevalent in urban existence. Whether individuals arrive battling ecological anxiety, experiencing burnout from work, or simply seeking a much-needed break, they consistently describe the act of gardening as simultaneously grounding and liberating.

As one gardener put it: “I have always lived in a house with a garden, but for the last few years I have been living here in the city centre, so green spaces are really essential for me… I really long for the forest and the countryside, but since I can’t do that every day, the garden is my substitute”. Another shared: “If it weren’t here, I would feel that something was missing”.

Others spoke of the calming rhythm of tasks like compost-sifting or simply finding solace in being alone among the plants. These are rare opportunities to focus on something tangible and immediate, moments where time itself seems to slow down. One gardener explained: “For example… we sift compost, or mix it with soil and sift it, that’s quite a monotonous task, and it can be like, okay, I’m not thinking about anything right now, I’m just doing this, I don’t need to pay attention”.

A deep sense of satisfaction often stems from the simple act of witnessing the direct results of one’s own labour. One gardener highlighted this: “I work, and then a squash or a tomato grows there, and I can cook it, take it home, eat it, share it with my neighbours and friends, so it’s a pleasant satisfaction to see the results of your own work”.

Repeatedly, gardeners emphasised a return to tangible, physical sensations–the feel of soil beneath fingernails, the reassuring weight of a watering can, the rich scent of sun-warmed compost. For those transitioning from high-pressure, screen-filled jobs, where outcomes are abstract or take months to materialise, growing plants offers an immediate and profound physical connection.

“Everything was so abstract, and then I wasn’t really in touch with the physical world and my body”, noted one participant. “Here it’s so different from home… that you move around and get a lot of colours, smells, textures, all kinds of things”.

Even the discomforts, like heat, mosquitoes, or physically demanding tasks like weeding and sawing, are viewed as part of the process, contributing to what many describe as a deeply restorative form of “active rest”. One gardener admitted, “it’s definitely a lot more stimulating than office work”.

For some, the garden offers a crucial coping mechanism in the face of climate anxiety. One participant shared how this initially led them to their garden: “I started coming to this garden because of climate anxiety, and it has helped me a lot… that I’m doing something with both hands.” The relief, they explained, stemmed from actively engaging—composting, weeding, planting—small actions that helped restore a sense of personal agency.

Occasionally, the garden also unexpectedly provides the mental space needed to support others. One gardener recounted the final years of a loved one’s terminal illness and the immense effort required to remain encouraging. She noticed a profound change in herself when making calls from the garden: “When I sat down on one of the benches in the shade after gardening and called from there, I knew I could be much more positive and resourceful in giving strength”. The garden, in this sense, offered a grounding environment where care and creativity could surface.

Allowing Nature to Guide the Process of Stewardship

Learning in Budapest’s community gardens isn’t like following a manual. Instead, it unfolds through hands-on engagement with compost heaps, during casual conversations by the worm bin, and in the inevitable frustration of trying something that doesn’t quite go as planned. Many gardeners didn’t describe a journey towards self-sufficiency but rather a process of becoming more observant, more attuned—learning to respect the rhythms of the garden, and by extension, the rhythms of life itself.

Several participants noted shifts in their everyday choices and overall awareness. Tending a shared plot instilled in some gardeners a profound sense of giving back. One individual described the reassurance found in caring for a communal area not for personal gain, but as an act of reciprocity: “It’s more relieving, to go to a place where I’m trying to give back to the environment, instead of always taking from it”.

This sense of reciprocity seemed to spill over into other areas—questioning consumption habits, thinking differently about waste. Another gardener noted that the simple act of sorting organic waste at home initiated a broader shift in their approach to consumption: “I started composting, and then came the earthworms… from there, everything followed”.

Learning in these spaces isn’t solely about acquiring new skills—it’s equally about unlearning—loosening the grip of control and allowing nature to guide the process of stewardship. One gardener initially approached the plot like a puzzle to be meticulously solved, tracking every plant and step, striving to comprehend the entire system. “I didn’t want anyone to interfere with the system,” they admitted, “because then I wouldn’t be able to follow what was happening”. But over time, something shifted. “And then I realised that I didn’t have to follow it. So it can be this way or that way, and nature will fill in the gaps and tell them what to do in time. And that’s natural. So handing over to nature the leadership”.

This moment—stepping back and allowing the garden to unfold naturally—felt less like giving up and more like a profound act of trust. Plans became looser, plants grew where they wanted to grow, and imperfection became acceptable. As one gardener shared: “It just evolves, has its own life”.

This kind of learning frequently happens collectively. Whether it’s through building a bee hotel together or a discussion by the worm bin, knowledge flows from peer to peer. It’s not about individual expertise in a traditional sense, but about shared curiosity. As one gardener explained: “Feel free to try out a new method, just let the others know that if they want to see how you do it, then show them, so they have a chance to learn and see it with their own eyes”.

Concerns about soil quality were also a topic of discussion. One participant shared: “There are harmful pollutants everywhere, in everything, and there is no way to avoid them… So how can you live with it? Permaculture helped me with this when they said that everything, like poison, can also be medicine in the right amount… And that reassured me somewhat. And then I saw that the system is designed this way”.

Beyond cultivation, some gardeners integrate practices like biodiversity tracking into their daily routine, using apps to photograph insects and small animals. As one explained: “It works by taking a photo of the animal or insect you see and uploading it to the app… If you know what it is, you can enter that information. However, if you don’t know, you can leave it blank… and someone who knows what it is will tell you…”. A photo of a beetle or a bee might seem like a small gesture, but it links a gardener’s personal curiosity with a global effort to map biodiversity.

Community Dynamics from the Garden’s Perspective

Community gardens in practice are far more fluid and negotiated spaces than one might imagine, continually shaped by the availability and evolving motivations of their members over time. People tend to come and go, their participation ebbs and flows with the seasons and individual situations. A significant portion of the work in these gardens is carried out without external support, relying instead on the initiative and dedication of their members.

It’s crucial to recognise that community in gardens isn’t always universally inclusive. While some gardens actively cultivate openness through neighbourhood initiatives, others operate more like private bubbles, often accessible only to plot-holders. One gardener expressed frustration with this disparity, noting that some “operate a completely closed system, envisioning community building exclusively among plot owners”. This contrast between more porous, self-organised spaces and formal, tightly managed ones reveals underlying tensions concerning ownership and inclusion, challenging the romanticised notion of gardens as inherently open civic platforms.

The existence of waiting lists illustrates just how competitive access to green space has become in Budapest. One gardener revealed the reality in their case: “The problem is that demand is much greater than our capacity. For example, we have a hundred people waiting to become garden members”.

This pressure underscores the significant gap between the widespread desire for community-based engagement and the limited capacity of existing initiatives to accommodate it. Even once a place is secured, participation brings its own set of challenges. Gardening requires time, energy, and a degree of physical effort, which can make these spaces less accessible to senior individuals or those with limited mobility. Similarly, those working long hours or juggling multiple responsibilities may simply lack the necessary time commitment. While some gardens function as flexible experiments, others adhere to more formal, institutionalised models, which can inadvertently lead to feelings of exclusion for some.

Connecting Neighbourhoods

Budapest’s community gardens connect to their surrounding neighbourhoods through seemingly small but significant gestures: shared compost buckets, open gates, and the exchange of stories. For many, these spaces become soft edges, blurring the lines between personal involvement and the wider rhythm of neighbourhood life.

Several gardeners described how local residents regularly bring their kitchen waste to the compost, fostering easy connections. “Many people are really friendly, and they bring compost,” one gardener remarked. “It can be such an open gate… Many more people could come than they do”.

In many present-day urban contexts, anonymity is the prevailing norm. However, one gardener found that their garden actively helped to reweave the fabric of daily social life. Living in a dense, fast-paced district, they observed how gardening fostered a sense of a “small village” within the urban grid.

The garden’s connective power extended even beyond residential boundaries. One participant, who doesn’t live in the district, explained: “I meet many more people, residents, in this neighborhood, even though I don’t live here… I’ve talked to them once or twice, and then they recognize me, and then there’s this close neighbor feeling.” Meanwhile, a local resident described the reciprocal experience: “I really like it when people come up to me and we can say hello to each other because we know each other”. It wasn’t about big gestures, but the quiet shift from impersonal interactions to genuine connection: eye contact, remembered names, lives intersecting in the middle of the street.

The gardens frequently become informal classrooms. One gardener spoke about bringing their young son into the garden and organising a birdhouse-building workshop that soon attracted other children: “We also have a raised bed that actually belongs to one of the local schools, and the parents there cultivate it”. For many urban children, it represents the first time the abstract distance between food and its origin turns into something they can see, smell, and physically hold.

Cities Where Ecological Care, Emotional Grounding, and Social Experimentation Coexist

Budapest’s community gardens are, by nature, messy and layered spaces. They don’t offer neat solutions or polished, predictable outcomes–and paradoxically, this may be their greatest strength. In a city largely shaped by asphalt and the relentless pace of acceleration, these gardens open up a slower, more relational way of being.

One garden, once a gravel-covered car park, now effectively holds rainwater, shades nearby pavements, and hums with diverse insect life. A participant expanded on how community gardens help cope with environmental challenges: “It would be very important to have as many of these as possible because if they weren’t there, the water would just flow through, and such large floods, which are becoming more and more common in the city, will cause a big problem”.

This perspective underscores that gardens are not merely spaces for leisure or learning but are an integral part of a broader urban strategy for resilience. They practically demonstrate how small-scale stewardship can help mitigate such as systemic vulnerabilities that extensive city infrastructure alone often struggles to address.

Ultimately, these gardens stretch the boundaries of what we can imagine cities could truly be. They illustrate how ecological care, emotional grounding, and social experimentation can seamlessly coexist within one small patch of earth. Perhaps what we truly need isn’t another grand vision of an ‘ideal city’, but rather more spaces like these – places where we can learn slowly, support one another imperfectly, and continue to grow.

Article by A. Tomoko Molnár with István Radnóti, PhD. Acknowledgement is due to fellow university students who assisted with the gathering and processing of interview material.