Stad in de Maak is an association set up to take on the redevelopment of vacant properties in Central Rotterdam, together with the local community. The association renovated six buildings, investing upfront the amount of loss the buildings were projected to generate for their owner, a housing corporation, in the coming 10 years. Stad in de Maak works on going beyond temporary vacancy management, by reaching permanence in affordable housing and working spaces through collective ownership and management.

“Our ambition is to bring properties into collective ownership and use”

This interview is an excerpt from the book Funding the Cooperative City: Community Finance and the Economy of Civic Spaces

In what context did you begin to work on Stad in de Maak?

This is an initiative that started from – and currently thrives in – the afterlife of the current financial crisis. A crisis that started out with toxic debts and real-estate speculations, emblematically bringing down Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008. Amidst the unfolding of this crisis, the non-for profit housing developer Havensteder bought these two buildings where we are today with the idea of demolishing and redeveloping them. At that time, in 2009, this probably still looked like a viable plan but that did not last very long. When the mortgage crisis hit the market in the Netherlands a little bit later in 2010, for real-estate owners, the world in which they operated suddenly changed.

For instance, the value of real-estate started to drop. As a result, they had buildings that in their accounting books were still listed at the pre-crisis value, while their actual value in the real-estate market had diminished significantly, which brought them into financial trouble. At the same time, during the years leading up to this financial crisis, the group of non-for-profit developers, to which Havensteder belongs, would move away from their core mission of providing affordable housing towards other products with a higher return on investment. The government also encouraged them to experiment to yield more return, which could then be invested into housing. During the crisis however, these risky operations started turning against them, resulting in financial deficiencies of billions of Euros. For instance, one of these non-for-profit housing developers, Vestia in Rotterdam, embarked in derivatives for almost 10 billion Euros, something that went terribly wrong. All the non-for-profit housing developers had to come together to rescue the ones which were about to go bust, which made a huge dent in their financial reserves. To add insult to injury, they were subsequently forced to make contributions to the state budget, because the government also found itself in trouble due to the financial crisis. As a result, the investment budget of these developers withered away.

How did housing developers react to this situation?

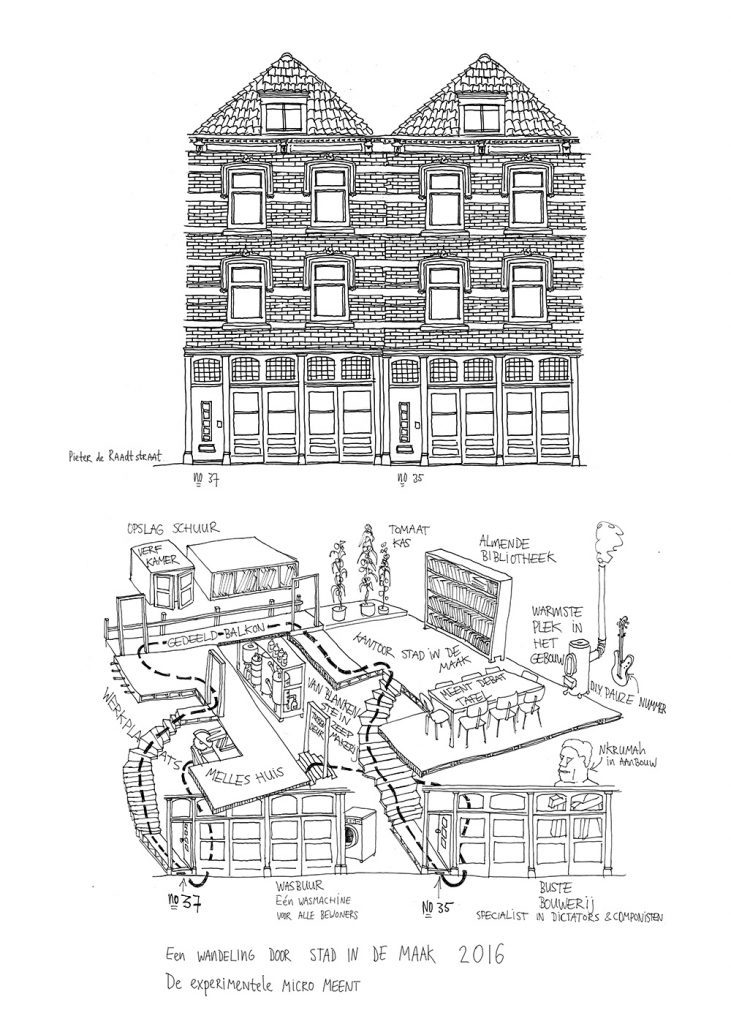

At that moment Havensteder found itself in a situation in which it could not any longer sustain part of its real-estate portfolio, so it had to focus on keeping the healthy parts. This means that there was suddenly no budget anymore for troublesome locations such as this one. In 2010, Havensteder made a quick-scan of the two buildings, with the help of two collectives from Rotterdam, Superuse Studio and Observatorium, to see what to do with these locations. It must be understood that within Havensteder this is seen as a controversial idea: why would they start investing in derelict places in times of crisis? There are other priorities. But there were also people within the organisation, who challenged this idea and wanted to protect the quality of the street and maintain the value of the assets, as they owned the majority of the buildings on the street. The commissioned quick-scan revealed that if Havensteder wanted to keep the buildings up and running, they would have to accept a loss of 60,000 Euros in the coming 8-10 years. That is actually not so much, even though it is in a period of crisis.

Following this, things slowed down, and it looked as if the study to revive the buildings would end up in a drawer. One of the people involved in the study, the artist Erik Jutten, took the initiative to push things further. He came up with an unconventional proposal: if Havensteder is willing to take the loss of 60.000 euros anyway over the period to come, why not take that loss entirely in day one instead? In this way, it can be handed over as an investment budget to a group of people that would take care of the two buildings and any remaining risks. In a certain way, this would allow us to ‘common’ the buildings with this group of people for a period of ten years, after which the properties would go back to the owner, if it was still there.

What role did you take in this process?

Ana Džokić, Piet Vollaard and myself joined Erik and put this proposition together. Our common motivation in the beginning was mainly curiosity: to see if we could do things differently. We spent a lot of time going through the details, like the economic model we had to get in place. The big challenge was of course finding a way to manage the buildings for ten years without us defaulting on it. We figured that, if Havensteder was ready to put in 60,000 Euros, around 75% of it would have gone into contractor costs, therefore we proposed to execute half of that work ourselves instead of outsourcing it. By doing so, we could free up a substantial part of the budget – because we could do things ourselves cheaper than a contractor, but it would also allow us to schedule and prioritise works differently, as we needed to urgently divert money to make some of the spaces inhabitable and create a cash-flow through renting them out. This is because we have to pay the bills, we have to pay the insurances, we have to pay the taxes… And we basically had no money ourselves, so to prioritise works to create an economically sustainable cash-flow was very urgent for us.

How did the housing developer like these ideas?

For Havensteder it was a deal with an untested partner: we had never worked with them before. But it was interesting for them because they hardly had any financial risks, no contingencies, and no management costs any longer. We would take all of this upon us for the next 10 years. After that, we just give back the property with no further economic loss than the 60.000 they had already booked. And while we negotiated over a period of many months, some level of trust began to develop amongst all the parties involved.

In October of 2013, we signed the agreement. A month later, work on site began: the buildings were in ruin and we had to quickly make them inhabitable. We had gone through a huge excel sheet for months and months, but we did not have much experience with doing these sorts of things, so we took on things quite intuitively. Meanwhile, we have grown a handful of buildings, and a few principles have emerged.

How do the buildings function economically?

First of all, we try to make each building a self-sustaining node (in economic, social and environmental terms) within a network. This is done to foster a more robust network, in which difficulties (or even the ‘collapse’ of one node) do not pose a threat to the viability of the overall network of buildings. In economic terms, this means that each building should generate enough resources to cover its own costs. In social terms, each building should take care of its own governance and use. In environmental terms, it should aim to become resource flow neutral (energy, water, etc.). We aim to create a common finance pool for the maintenance and expansion of this platform. All the inhabitants and users of the buildings, through payment for the right of usage, generate a (modest) flow of finance that contributes to this common finance pool. From this, the activities to sustain the platform (a baseline income for those responsible) are being financed. Given enough nodes in the network (scale), a revolving investment fund to expand the network could be created.

From the very beginning on, we have maintained a minimalist (or no-nonsense) approach to investments. If affordability is at the core, invest what is minimally necessary. For instance, by putting functional, rather than aesthetic concerns at the core. By re-using, upcycling, or working with donated materials. By improvising if the use span of a building is limited, as long as safety is not compromised. And by being prepared to lower the comfort threshold in exchange for lower existential pressures (usage fee).

While working on the first buildings, we discovered that it would be important to replace monetary flows with non-monetary alternatives, where possible. As both the inhabitants and users of buildings and the platform itself face a lack of mainstream money, part of the financial pressure can be diverted by conducting transactions in other ‘currencies’: worktime or materials, for instance.

How do the activities taking place in the buildings impact the neighbourhood?

We try to bring community activity, but also production back into the buildings, into the streets, and into the neighbourhood. Some things are being tested right now, like a workshop. There is a community brewery starting up, a micro-cinema, a launderette, even some production of detergent … In the coming months there we will have a number of trials to see how we can create a neighbourhood economy. It is crucial to keep space open for such uses and experiments. Each building therefore, has a commons (“meent” in Dutch), accessible for social or productive undertakings. We decided to keep financial pressures away from these common spaces, and cover the costs to keep them open through a contribution from all the users.

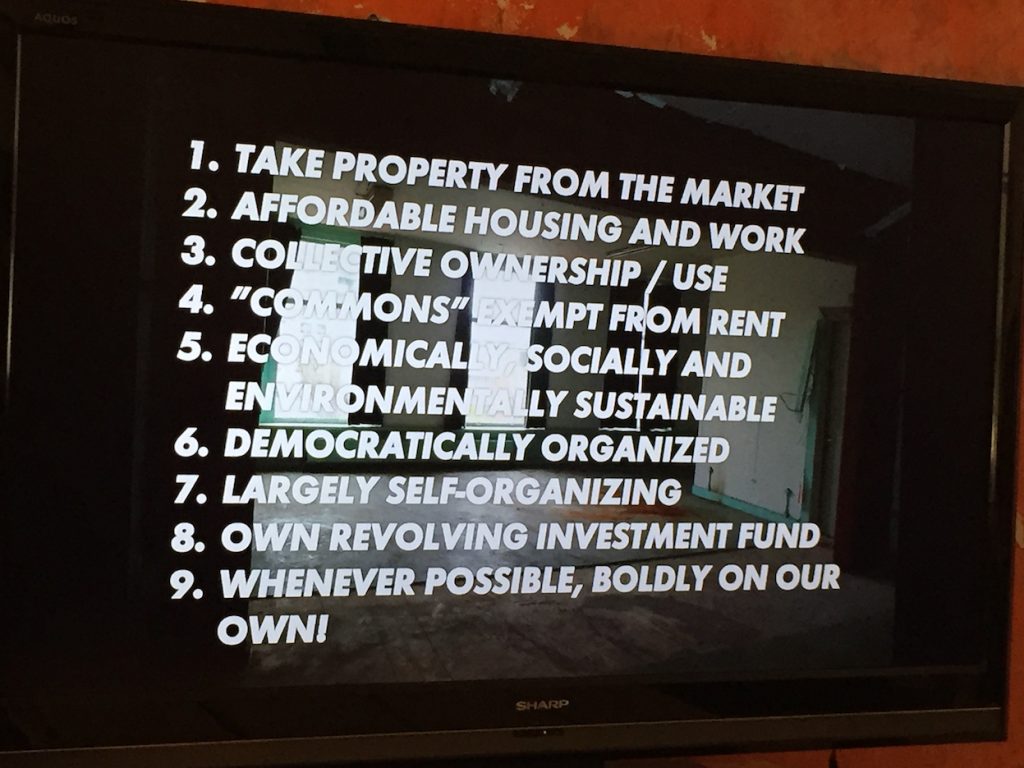

We said straight from the beginning that City in the Making – with its current temporary use of buildings – is a sort of training condition for what is yet to come. For us, the next step is to go beyond this temporary exploitation of vacant properties. Now we can do this because there has been an economic crisis but this is not sustainable in the future. Our ambition is to take the properties out of the market, to make them available for affordable housing and work, and to bring them into collective ownership and use.

Interview with Marc Neelen on 26 May 2016