Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas is a platform to support citizen projects in Madrid. Initiated by the architecture office Estudio SIC, the platform maps and brings together citizen initiatives that shape the city’s various neighbourhoods, identifying their competences and needs. Based on this mapping process and the related research, Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas teamed up with the Madrid Municipality and six other partners and made a successful bid in the European Union’s Urban Innovative Actions competition with the Mares Madrid project.

“We need to put in practice all the competences, knowledge and capacities of citizens”

How did you start researching and mapping citizen initiatives?

In our work, we understand that if we want to work with the city, we need to understand how citizen practices are developing in different parts of the city. Cartography is the first step: getting to know the actors and how they are acting in their own practice, public or community space.

In the 2000s, the development of Madrid was dominated by new housing at the city’s periphery, with the contribution of the largest construction companies. More than 35% of the city’s area was developed between 2000 and 2010, encouraged both by banks and public administrations. When the economic crisis made clear that this model was not sustainable anymore, and exposed many people to the risk of losing their homes, many initiatives were formed across the country to counteract the official urban development logic through a real process of self-organisation and self-empowerment. In this context of resistance, many initiatives grew together and this activism affected every sphere of the city of Madrid.

We began to map these initiatives, together with places of evictions, and this created a lot of data that was previously not available. The map was very useful in helping organisations like the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH, Platform for People Affected by Mortgages), to highlight that evictions are not an individual problem but a collective one. We called this the cartography of the extitutional process. Later, we began to analyse other projects of activism, governance, education and culture, trying to draw their spaces and relationships: we wanted to show the diversity of citizen initiatives and help people understand the links between public space, citizenship and self-management and the affective capital that these projects develop, along with the motivations of people to join these initiatives.

We aimed at visualising what exists, and making it appear as never before. We realised connections we did not know about before, and the emergence of networks by initiatives in Madrid neighbourhoods, like the networks organised around educational activities for young people, feminist centres, food production cooperatives or seed banks that all have a complex urbanism behind seemingly simply initiatives.

What is the result of this mapping process?

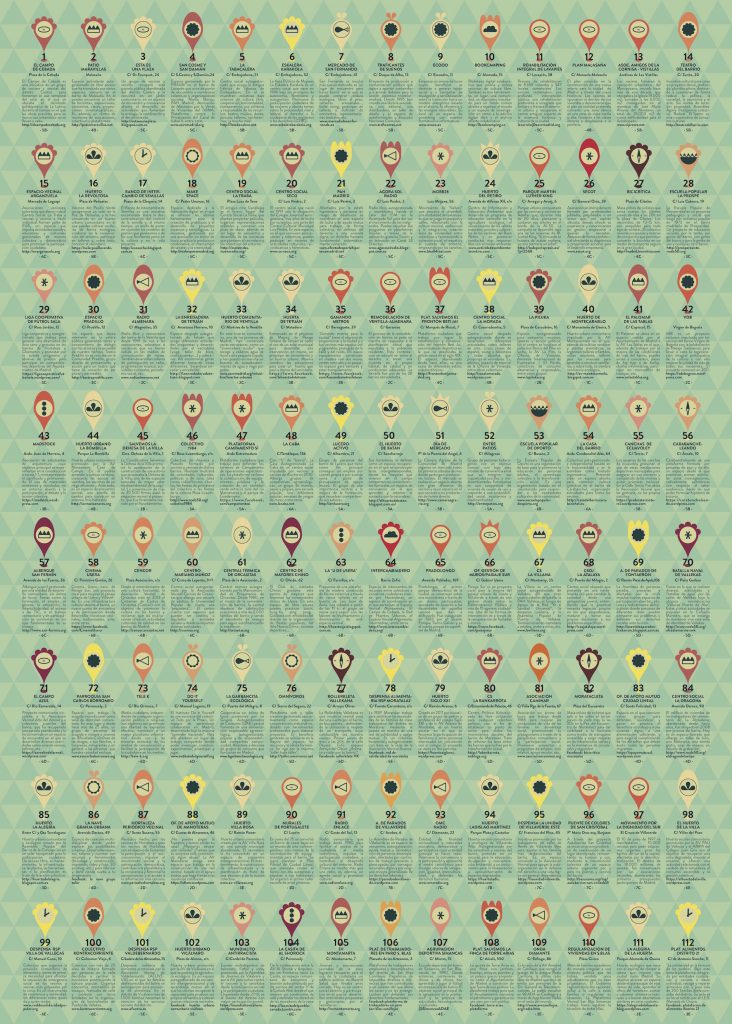

Los Madriles is the first official map of citizen initiatives. This map was published five months after the arrival of the new mayor. It was created by a bottom-up initiative, but in relationship with the city council that wanted to embrace citizen initiatives and create stronger connections with the civil sector. We are in a moment of change: with the new mayor, citizen movements entered the Madrid administration with a new party, a kind of a citizen party, similarly to other Spanish cities like Barcelona, La Coruna, Valencia.

The City Council wanted to support this research and therefore we made the map: the paper version includes around 100 initiatives, and the digital platform civics.es includes another 400 more; a network of very different activities, but all connected. However, we could not cover the whole city. We understood that many initiatives only become visible when we go to certain neighbourhoods and focus on them. Both maps are more a process than a result. The paper version is reprinted on a regular basis and is very successful.

What kinds of initiatives are included in the map?

The maps feature a mix of bottom-up citizen initiatives and established associations, some of which are 30 years old, in various neighbourhoods of Madrid. We have a specific understanding of citizen innovation here, with a very limited economic dimension. For example, we had debates about some cooperatives that do very important work but have a commercial basis and therefore were not included in the map in the end. Giving a more important role to economic activities within citizen initiatives has long been a kind of a taboo. It makes initiatives here very different from their Northern European counterparts: community-led projects we visited in the Netherlands, Germany or even Hungary, have a strong relationship with private ownership, and refuse to rely on public administrations alone. In contrast, here in Madrid, everyone asks the administration for resources.

But accessing public properties is slow and bureaucratic, and the administration wants to control the use of these spaces, much more than in Northern European countries such as in Amsterdam, for instance. All of the urban processes giving space to citizen initiatives need capital and resources, but they rarely develop economic models to sustain themselves. It is often voluntary work or political activism. Citizen initiatives, like urban gardens, produce results but do not know how to become economically productive. For instance, the municipality gives space to citizen initiatives but does not allow them to be productive in these spaces, they are not allowed to have economic activities in these spaces. For me this is very absurd because the aim is not to earn money with these activities, but to circulate the values that you produced with your practice.

In turn, many processes in the social and solidarity economy are very traditional, not very innovative and inclusive. Recently, there has been a transition in this: the traditional social economy initiatives began to connect better with informal citizen innovation processes. We need to better connect these realms to help make them really change the city.

What did you learn from the mapping process?

Our vision is to understand the city better, beyond micro-urbanism and micro-politics. What is interesting for me is the complexity of how different projects grow together into a network of projects, a citizen network that is very strong. This is how Madrid works: there are strong relationships between initiatives, we do a lot of things together and engage with each other in many ways. Many of these initiatives are not tangible, not physical spaces but online platforms or economic activities that are very much related to the urban landscape through their focus on energy, mobility, food or waste.

How do citizen initiatives and economic activities relate to each other in your map?

When we engaged in discussions in Berlin at the first Funding the Cooperative City workshop in 2014, the event’s focus on civic economy changed our approach to citizen initiatives. As many of Madrid’s citizen projects are precarious, ephemeral, instant actions or acts of resistance, we try to connect them with the social and solidarity economy sector, and try to understand how we can rely on citizen competences to transform the local economy.

When we engaged in discussions in Berlin at the first Funding the Cooperative City workshop in 2014, the event’s focus on civic economy changed our approach to citizen initiatives. As many of Madrid’s citizen projects are precarious, ephemeral, instant actions or acts of resistance, we try to connect them with the social and solidarity economy sector, and try to understand how we can rely on citizen competences to transform the local economy.

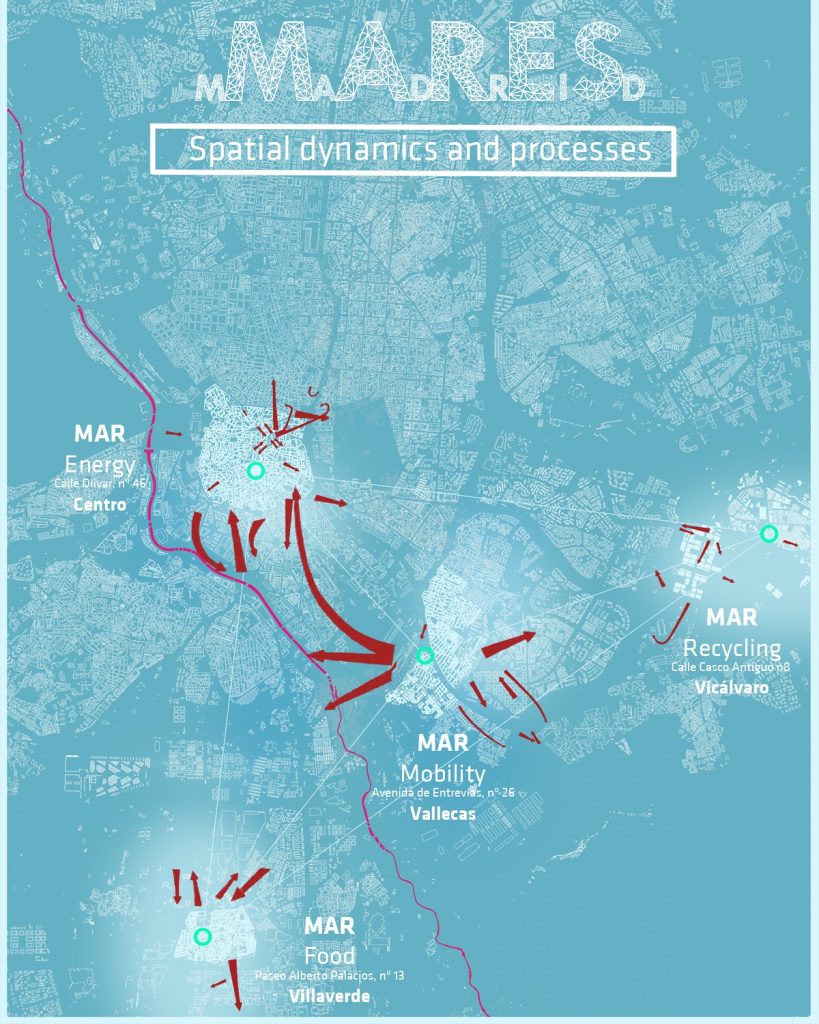

We are now working on a project, Mares Madrid, together with the City Council, to provide buildings for local initiatives to work together in a strong relationship with their neighbourhood and develop economic activities that affect urban development. For this, we need to understand the competences, knowledge and capacities of citizens to develop new companies, new cooperatives, new urban services around the topics of mobility, waste, food and energy in four areas of Madrid. We are aiming at linking initiatives in a circular way, to connect buildings, public spaces, waste, and agricultural production to local economic development.

In Mares, we have four groups of partners: social and solidarity economy organisations, the public agency of employment, the municipality’s economic development department and the architects and citizen initiatives represented partly by us. We are principally responsible for mapping citizen initiatives in the targeted neighbourhoods, for the regeneration of four buildings and the spatial dynamics generated around them, but contribute to the other aspects as well. The project will also allow many different actors to participate, collaborate and co-produce, including local citizen initiatives and small companies that will cooperate around topics of recycling, food, energy and mobility, creating new jobs and new enterprises.

The Mares project is very interesting because it connects urban development with economy in a circular, or metabolic and resilient way. The scale of the project goes beyond a small or medium intervention; it addresses the whole city, while dealing with local spaces and neighbourhoods. When we go to some of the neighbourhoods the project concentrates on, we meet many initiatives that we did not know existed, because they act at a very local scale and we understand the specific competences and capabilities of people in the given area that can be different from other districts. It is not so much about joining architecture and economy in a specific project, but about how these processes can transform the Southern part of Madrid in the next three years.

Interview with Mauro Gil-Fournier, Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas (VIC)

20 April 2016 – 19 October 2016