“Super, the festival of peripheries” was started in Milan in 2015 by an interdisciplinary group of professionals. The event was initially conceived to create a more accurate, diverse and complex overview of the city’s outer neighbourhoods by reporting experiences of active citizens and entities, as well as stories about the daily life of those territories. Beyond this overview, Super also reimagined simple forms of action to initiate a process of communication, networking and cross-fertilization among civic initiatives that still keep on bringing innovation in the life of the Milan area.

Milan, April 2020. In full lockdown, in a city where you cannot leave your home unless risking to incur heavy fines, a webradio starts streaming eight episodes of a brand new broadcast reporting the life in public housing buildings during the Covid-19 pandemic. Interviews, columns and activities tell about and address those who live in those neighbourhoods. A spotlight on their humanity, with stories and experiences of mutual help that have developed there during this period of emergency, far from the media attention. The transmission collects a growing number of contributions by inhabitants, artists, associations, bookshops and other organisations from all over the city.

A month later, with the city getting slowly out of the quarantine, the city hosts “Milan takes a new tour,” a day of mobilisation to demand the local administration to do everything in its power to make Milano a bicycle-friendly city. 80 organisations, among them associations, cooperatives and other third sector entities, foundations and research agencies, bike kitchen, shops and citizens groups, join the rally.

These two initiatives listed above, albeit very different, have one thing in common: they have been both promoted by the group animating “Super, the Festival of peripheries.” This fact offers at first sight a hint of the festival’s particularity: from the beginning, Super has been working with different formats of initiatives and created unprecedented collaboration networks – in regard to the diversity of their components – in order to engage and sensitise the civil society at every level. But to understand Super better, it is necessary to go back to its starting point and trace back its origins.

Back in 2015: the “showcase” city

Super was first conceived in 2015, which was a very special year for Milan: on 1 May, the World EXPO Milano 2015 finally opened. Its preparation had taken long: seven years, marked out by huge delays, which motivated the entrustment of exceptional powers to EXPO managers by the central government, and led to arrests and denunciations due to alleged abuses of this authority. At the administrative level, Milan had been led since 2011 by Giuliano Pisapia and the first progressive, left-wing council after decades. Its government agenda though, once chose to confirm the EXPO, had to undergo a profound change. The municipal coffers had been left empty by the previous council, and all the funds made available by the central and regional governments had to cover unpostponable expenses for the completion of infrastructures and major works for the long-awaited global event. The 11 million tourists who visited Milan for the year of the EXPO strolled in a new district set to shine, a huge showcase for the city that has been experiencing a tourist renaissance since 2015, becoming the second destination in Italy by number of visits.

Beyond this “showcase,” however, lied the real city: neighbourhoods that, to varying degrees, concentrated uneasy situations, and which increasingly suffered from lower investments of the administration’s resources. During the autumn and winter of 2014, mainstream media communication was presenting the Milanese suburbs as abandoned to drug dealing and crime, taken hostage by immigrants and illegal occupations. The Italian archistar Renzo Piano, newly elected as a life senator of the Italian Republic, compared Italian suburbs to “deserts” and “dormitories,” and demanded a gigantic darning and mending operation which had to connect these territories to city centres. His words were cited by all the more important Italian newspapers and TVs, enhancing their distorted portrait of peripheries.

In this setting, a group of different professionals gathered around Federica Verona, the first initiator of the Super festival, and began to discuss and question this trend. They all shared an interest in the peripheries and agreed that local and national media were adopting a toxic narrative to describe them, which did not depict the reality that the suburban neighbourhoods truly lived. The group therefore decided to launch a collective, non-profit project to provide more faithful insights of these contexts. To do so, they agreed on two key objectives:

- to explore people and organisations whose resources and skills help activate original and innovative projects in these areas of the city, far from the centre and its stable / sedimented / institutionalised systems;

- to focus as much as possible on social processes, on personal stories and on organisations capable of awakening and activating the resources that generate these changes.

Knowledge requires time:the idea of a “slow” festival

This is the origin of Super, the Festival of Peripheries: its name comes from the combination of two simple preposition, “su” and “per” – which in Italian language correspond to on and to – which convey the idea of a thematic project (on peripheries) with a specific goal (to spread insights and reflections coming from the suburbs). The Super group was driven by intellectual curiosity and civil passion, which aimed at rousing the same interest of those who did not know these territories: a large part of the Milanese population. Super then adopted the “familiar” format of a festival, in order to be more appealing for the media and for Milanese people, and at the same time to be free and flexible to develop its actions, hosting events and projects accordingly with the evolving knowledge of peripheral milieux.

From the beginning, it has been evident that Super required dedication and time, as its essence laid on the construction of personal bond among interviewers and the people telling their own experiences. Time was even more a key resource to the project: there was a big need for it, in order to be able to slow down and really listen, leaving behind all clichés and simplifications. The concept of the festival was, therefore, folded, and released from its commercial, fast-consumption imaginary.

Super was conceived as a “slow” festival – it was supposed to last a year, but went on and on. As a first step, a sequence of tours was planned in the various suburbs. More than just walks, the tours were most of all neighbourhood visits to meet with essential actors, people active in different groups animating that territory. These multiple interviews (6-7 for each tour) were always accompanied by photographic and video documentation of the territorial contexts. Each tour played the role of a narrative unit of the exploration of the suburbs: a montage of all the visual documentation and interviews fed into a collective diary, which was published periodically on the Super website and on its main communication channels. The communication of the tours followed three different lines:

– a real time narration, with images and short texts documenting the different encounters we had during each tour on our Facebook page and twitter;

– a more diffuse presentation of the specific context of each neighbourhood, which we committed ourselves to provide soon after each visit on our website by assembling extensive reports of the talk we had with local initiatives.

– a more-in-depth analysis, which took advantage of the audio and video recordings of every talk we had.

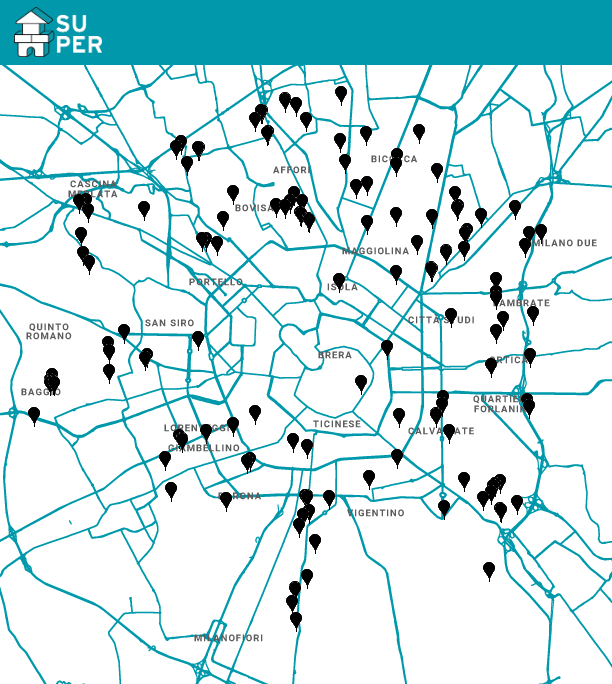

In this process, Super collected a very rich digital archive, which was the starting point for a number of different research projects, focusing on specific topics (urban production of food through gardening and agricultural projects, the relation of traditional and digital craftsmanship in the city, informal use of public space). We set up a database containing each initiatives’ contact person, transcriptions of the interviews, images and videos. We were not truly aware of the amount of data we were about to collect, so as the research material was getting bigger and bigger, we decided to publish new tools to help orientate in this complexity: first, we released a public map of the citizen initiatives we met, that was meant to facilitate contacts among different actors of the city, and and later Nicla Dattomo and Gianmaria Sforza developed an smartphone app, ATPER (ATlante PERiferico) which was conceived as an exploration tool for people crossing the city and willing to get in touch with the reality Super had mapped. The result integrated superficial glances and in-depth readings, provided by those who had lived and been active in these territories for years.

Life in hoods: variable geometries

From December 2015 to July 2017, Super carried out 24 tours in the outer neighbourhoods of Milan, contacting more than 250 local stakeholders to organise meetings and interviewing more than 160 of them. The spectrum of interviews was very broad: informal groups, associations, small enterprises, schools, cooperatives and other entities of the third sector involved in different fields (culture, social services, education, housing, entertainment). Some of them were selected for specific aspects of their activity: food production, redevelopment of spaces / activation of networks, ecology and sustainability, professions and new economies, managing social problems, offering culture and training. Others came into our scope indirectly: the contact with a local active group naturally brought suggestions, and it widened our gaze even further. In areas where associations were weaker, for instance, we were often shown shops and commercial activities as animators of the neighbourhood and social hubs to encounter. In other cases, the presence of neighbourhood networks and coordination allowed us to recognise important actors even in subjects that would otherwise have remained hidden.

The tours provided a particular and original image of each neighbourhood and its life, which were very far from the narratives that had been made of these areas up to that point. Super’s first result was to offer fresh looks and unreleased points of view, enhancing experiences which often risked to be overlooked in a layered and complex city. The stories of the actors that we collected during the festival enriched us, revealing that proximity – to communities and territories – was a fundamental prerequisite to frame, prevent or respond to problems arising in the neighbourhoods themselves.

The portraits Super provided for the twenty-four neighbourhoods cannot be estimated as exhaustive though: the interviews just covered a part of the active citizen initiatives in each area, selected according to indicators and our sensitivity, and corresponding to an extremely precise period (2015-2017). The territories, communities and individuals who have inhabited them in the last three years have undoubtedly expressed new needs and desires; consequently, the overall picture has already changed. The experience of the pandemic and the lockdown, which has closed people in their homes for two months in Spring 2020, will certainly have accelerated some of these dynamics and will have given rise to others that we still cannot foresee.

Peripheries as civic innovation

The emergence of extremely rich and diverse experiences has made it possible to recognise the peripheries – those of Milan as much as others in the world – as natural laboratories for innovation open to the future, a condition often ignored by local and national policies. In the case of Milan, this was partly due to the coexistence of more historical citizen initiatives born in the 1980s and 1990s, and a number of new ones set in motion by expectations of the EXPO and further supported by the rise of a centre-left administration. During the tours it appeared very clear that while in a few neighbourhoods there was some sort of coordination between old and new actors of civic engagement, in others there was little inclination for these initiatives to bond together, with almost no network activity at the city level.

Super had the chance to focus on this problem and take it as an opportunity to expand the movement of citizen initiatives: exploring the Milanese peripheries created the conditions to construct local networks of debate, collaboration and exchange among different actors, connected either by their location or by field of activity. We made connection and network-building among citizen initiatives the central topic of a project funded by the European Cultural Foundation within the IDEA CAMP programme. In 2018-2019, Super organized a cycle of seven workshops in order to facilitate and promote interaction and mutual knowledge. The ECF grant made us possible to implement a second analysis of the whole interview archive in order to define recurring, non-specific and original topics considered essential for the Milanese milieu that could stimulate the discussion among initiatives. The workshops also included experts from other Italian cities invited to enrich the discussion.

The outcomes of these processes, in the form of documentations and printed reports, were presented to public and private institutions responsible for the development of the city’s social and cultural policies. Super has always maintained a fair distance from these big urban stakeholders: a condition, in our view, that has eased a relationship of trust and complicity with NGOs and other local actors. It was a prerequisite, on the one hand, to be able to freely propose activities, experiments and collective initiatives, which beyond their measurable result have allowed the growth of bonds and mutual knowledge. It was also a key condition, on the other hand, to succeed in having local initiatives accept to host events and presentations – even a three-days long urban program –, welcoming people from all over the city and raising awareness about the real life of the peripheries.

In the last three years, we have been pleased to observe the rise of innovative experimentations based on the involvement of civic initiatives and NGOs in inclusive platforms launched by the local administration and other public and private institutions. It is undoubtedly the effect of general trends in urban policies at the Italian and European levels, but we think that our initiative has also had a role in it. Some of these new platforms have played a fundamental role in organising support and solidarity toward thousands of families who, during the lockdown, experienced situations of extreme difficulty and, thanks to these networks, received food parcels or direct economic support. In most of the neighbourhoods, however, further forms of organisation and coordination responded to needs that the most institutional networks were unable to satisfy. This proves once again the centrality and generativity of the territories in producing action for potential change and improvement of the conditions of the communities. This is the reason why Super’s research mission has not lost its relevance, on the contrary: we generally register a higher sensitivity among public and private stakeholders toward local civic ecosystems. In two cases already, we have been invited to help, facilitate and enhance new processes of exchange, connection and matchmaking of needs and desires among important urban actors and the neighbourhoods they operate in. It is something we could not have even imagined during our first years of exploration, when our methodology and our interests in these small and peripheral civic actors were still completely unusual: nevertheless, it is something the city, its communities and its citizens will benefit from, and we are glad that we have played a role in this process.

Carlo Venegoni, urban researcher, member of Super collective

This article appears in the book The Power of Civic Ecosystems: How community spaces and their networks make our cities more cooperative, fair and resilient.