Energy transition offers major structural changes to energy supply and consumption in our energy system in order to limit climate change. Especially after the breakout of the war in Ukraine, we have seen how fragile our energy supply is in Europe, depending on interest-driven decisions in undemocratic countries, ultimately affecting our economy and the most fragile members of society. Energy poverty in housing and in small businesses has triggered severe effects across our cities, with many people struggling to pay bills at the end of the month. Can energy be produced in an ethical way, distributed according to transparent and democratic principles and be available at a low cost so to be accessible for all? A great opportunity is offered by the development of the energy transition at a local scale, targeting neighbourhoods, industrial facilities, and cultural hubs, among others, to produce and consume renewable energy—these are energy communities. For this model to be sustainable in the long term, we must develop city-wide networks, promoted by public administrations and co-managed locally by private and civic stakeholders.

Embedding the energy crisis in a larger geopolitical context

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered a profound energy crisis in Europe, with gas consumption from Russia being interrupted across Europe. From an economic and social point of view, the war’s impact has been particularly strong on low-income groups and small businesses as the energy prices skyrocketed. From an environmental point of view, many European countries struggled to find sufficient energy alternatives to gas, therefore reactivating even already closed coal mines, whilst planning the development of a new energy mix. Particularly affected were countries dependent on Russian gas and oil, with few energy alternatives, especially when local industry was reliant on imported gas. These countries include Germany, Europe’s largest economy and its biggest industrial producer, as well as Central and Eastern European countries, traditionally highly reliant on imported gas from Russia. As a result, countries like Italy, another great importer of gas for heating, set up deals with other gas producing countries, like Algeria, further deepening their dependence on non-democratic and non-transparent interests.

Back in 2019 the European Commission, under Ursula von der Leyen’s presidency, announced the Green Deal to address the pressing issue of climate change through a sustainable and competitive economy. The key ambitions include climate neutrality (net-zero greenhouse gas emissions) by 2050 and reaching by 2030 the reduced emissions target of 55% compared to the 1990 levels. These goals will be pursued by bringing the European economy towards a green economy, by protecting nature and biodiversity, and shifting food systems towards a sustainable production model.

The ambitious plan was first delayed due to the COVID-19 crisis, and later, the war in Ukraine, which delayed the energy transition because of the increased use of fossil fuel. As a result, further impacted by rising inflation, the initially allocated budget has had a great number of changes: the renewable energy fund, in particular the Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform (STEP), which supports renewable energy projects, was reduced to redirect funds towards defence, whilst the RePowerEU plan, aiming at reducing dependency on Russian fossil fuels, has received significant funding but it is unclear how it will impact the overall Green Deal budget.

In such a complex geopolitical and economic context, who will pay for the energy transitions costs?

As a result of this uncertainty, energy transition has become a battle field of the political debate at European level, with far right and right wing populist parties downplaying or even denying climate change, and therefore challenging the need to take counter measures and developing or upholding green policies. In fact, these parties argue that the energy transition will lead to job losses, higher energy costs, and economic decline. The European election results show how right wing parties are ascendant, whilst the Greens, who in 2019 won their largest share of seats in European parliamentary elections, have performed more poorly. The reality beneath this debate is that the energy transition’s economic models, despite the public subsidies that the Green Deal may provide, are very reliant on personal expenses on the consumer side, with those on a lower income being extremely worried about the possibility of covering such costs. If electric cars remain as expensive as today, how will workers, dependent on their personal vehicle, be able to afford such transition? If household energy expenses remain so high, how will people with vulnerable socio-economic statusbe able to afford it?

Meanwhile, over the past years an increasing attention towards environmental justice is gaining more public attention through media, activism and civic participation. A lot of the civic response to environmental issues is to refer to eco-anxiety, the emotional and psychological distress experienced by individuals in relation to the current and anticipated impacts of climate change and environmental degradation, largely present amongst young people. Therefore, youth involvement in the call for environmental justice stems from the recognition that they will bear the brunt of the long-term consequences of environmental degradation, climate change, and other ecological issues. They are witnessing the increasing frequency of extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and other manifestations of climate change that pose threats to their future. Yet young people often feel that they are not adequately represented in decision-making processes that shape environmental policies, which is why many have taken part in global activist movements.

Amongst these are the youth climate movement Fridays for Future, inspired by activists like Greta Thunberg, which has mobilised young people to demand action against climate change, and Extinction Rebellion (XR), an environmental movement which has gained great media attention because of the pacific and provocative actions to advocate for urgent action in addressing the climate crisis and biodiversity loss. So, whilst it appears that a part of global geopolitical and economic actors still expresses considerable scepticism about the severity of the climate crisis, and hold back institutions from taking remediation measures, civil society, and especially youth, are experimenting new ways to increase awareness and build alternatives.

A way forward: Energy Communities

One of the alternatives gaining great attention lately are energy communities: groups of citizens, businesses and local governments that jointly produce, consume, and share renewable energy, greatly contributing to a more sustainable and decentralized energy system. Energy communities are a way for people to take control of their energy future.

Recognising the importance of energy communities, the European Union has been a strong advocate for them, supporting their potential to accelerate the clean energy transition and empower citizens. The Clean Energy Package adopted in 2019 has been the foundation for energy communities in Europe, introducing the package for both Citizen Energy Communities (CECs), primarily focused on energy consumption and potentially shared energy production, and Renewable Energy Communities (RECs): primarily focused on producing renewable energy for their members. The core elements of this EU policy are the legal recognition, providing an EU framework and allowing to operate under different legal forms, facilitating self-consumption and sharing of energy, as well as ensuring the setup of support scheme and the simplification of administrative procedures from Member States.

Recently, the Fit for 55 package, put in place to ensure that EU policies are in line with the climate goals agreed by the Council and the European Parliament, further strengthens the role of energy communities by creating more opportunities to contribute to the clear energy transition targets. Nevertheless, the implementation of energy communities at European level is still hindered by the complex regulatory environment, as each country has different national regulations, access to finance, as initial investment is usually up to the communities themselves, and technical expertise, as building the necessary skills and knowledge within communities can be time-consuming. Despite these challenges, energy communities offer significant opportunities to create a more sustainable energy system and have been increasingly growing across Europe.

Given their often grassroots nature Europe-wide, it is still difficult to have a fully comprehensive overview of energy communities. It is estimated that there are 10,540 energy community initiatives and 22,830 projects across 30 European countries that involve around 2 million people and have led to the installation of 7.2-9.9 GW of renewable capacity. The uptake across Europe is diverse, with some countries having emerged as leaders in energy communities, such as Germany, a pioneer in renewable energy, Italy with a focus on solar energy communities, especially in rural areas, and Spain, with a mix if energy cooperatives and citizens-owned projects. A Europe-wide map has been published by the European Commission; despite not providing an updated overview, it shows the spreading and a number of relevant case studies, often fostered by European research grants.

Energy4All: Building communities for positive energy districts

Amongst the ongoing EU-funded projects on energy communities across the continent is the Energy4All project, whose main objective is to explore and highlight the role of communities and the human dimension in designing and implementing Positive Energy Districts (PEDs) and Energy Communities (ECs).

The project is developing participatory governance practices in the industrial and civic sectors to support the development of positive energy districts, identifying barriers to PEDs and ECs adoption to address shared challenges and develop a common ground for action. By tracking community engagement and policy changes, the project disseminates findings to amplify impact on civil society and policy environments, supporting cities in transitioning towards climate neutrality.

Energy4All is a Driving Urban Transitions project led by Eutropian, developing participatory governance practices to support the development of positive energy districts. Image (cc): Energy4All

Energy4All is working with local NGOs, cooperatives, municipalities, universities and engineering companies in six pilot projects in Rome (Italy), Styria (Austria), Budapest (Hungary) and Stavanger (Norway) to establish and strengthen local energy communities.

The energy community in the Quarticciolo neighbourhood of Rome, in Italy, aims to create a resilient network to tackle energy poverty, by providing affordable and sustainable energy solutions to residents, organized around the housing estate’s community boxing gym. By fostering collective action, this initiative seeks to strengthen the environmental and social empowerment of the inhabitants, promoting sustainable practices and solidarity. Additionally, the community will play a critical role in identifying gaps in current legislation, leveraging their insights to produce informed recommendations for policymakers, thereby driving legislative improvements that support a broader adoption of community-based energy solutions.

The Quarticciolo neighbourhood consists of a social housing estate in a state of decay where energy efficiency and the right to live in decent homes are a dream. Inequalities are exacerbated by high post-pandemic utility bills. Quarticciolo remains an area characterised by an absence of services, high housing density, high unemployment and crime rates. However, the great void of institutions has been partly filled by the grassroots initiatives that have sprung up within the borough. The Palestra Popolare Quarticciolo has been at the heart of the neighbourhood, working tirelessly to connect and empower residents. Despite the challenges faced – from business closures and family evictions to schools at risk of shutting down – this community gym, transformed from an abandoned boiler room, stands strong, embodying the values of solidarity and mutual support. Currently the community has set up the association that will run the energy community and is searching for the necessary finances to install the solar panels, which will be posed on the roof of the gym. A great challenge for this community is accessing initial investment capital as the local community is composed of low income families that don’t have the banking credentials to access mortgages.

Graz Umgebung Süd in Austria is a conglomeration of six municipalities that came together to take advantage of the opportunities offered by energy communities and strengthen regional energy independence. The municipalities of Fernitz-Mellach, Gössendorf, Hart bei Graz, Hausmannstätten, Raaba-Grambach and Vasoldsberg have been working together for twenty years in the areas of public transport and business; this provides a strong basis for their cooperation in joint energy production and consumption. Cross-municipal energy communities that are initiated and operated by the municipalities themselves are still rare in Austria. The six municipalities together represent almost 30,000 inhabitants, and a large number of small and medium-sized enterprises. Due to the large number of potential participants, there is a good balance between producers and consumers of electrical energy. Due to the leadership of the municipalities themselves, acceptance among all citizens and local businesses is very high. Their bet is that cross-municipal corporation pays off, even if it takes more effort in the beginning, allowing to maximise the benefits of energy communities and to strengthen the social cohesion amongst inhabitants. The biggest challenge is to align the different wishes of the municipalities with a common goal, from financing of the PV systems to electricity prices in the community.

Another case study in Austria is St. Margarethen in Lebring, a pioneering energy community in a rural region, that aims to develop effective business models and to strengthen social cohesion by overcoming challenges connected to the information gaps and administrative barriers. The energy community supports local inhabitants by sharing energy from renewable sources between all members: this will strengthen the energy independence of the community, actively contributing to the energy transition and supporting local businesses. The village of St. Margarethen-Lebring is a municipality with 2,300 inhabitants, where the initiators are a community-based association that focuses on energy efficiency in the community, so called e5-Municipality. The energy community was founded at the end of 2023, after a relatively short planning phase of around six months. The energy exchange with the founding team began in January 2024. The population was then invited to participate and there are now more than 60 members, with a strong upward trend. Although the legal basis for renewable energy communities has been in place in Austria since 2021, there are still many legal and tax uncertainties, therefore the involvement of external experts in the electricity industry, law and taxes is absolutely essential to support the thriving of energy communities and overcome the reservations that the public may have against a new legal construct.

GU-Süd: Regional collaboration for energy independence and sustainability. Photo (c) So-strom

By reusing and transforming waste heat from heavy industrial processes into novel energy sources to benefit the neighbourhood, the pilot area of Hillevåg, in the Norwegian city of Stavanger is developing a collaboration between industry and the public sector to reuse waste energy and water. PED Hillevåg explores public-private partnership models to reuse waste heat from heavy industrial processes linked to production of animal feedstock. There are novel possibilities to draw upon this energy source in future neighbourhood development.

Public-private partnerships and heavy industrial processes have received very limited attention in PED initiatives to date. Yet to displace and reduce major carbon emissions and optimise energy usage, actors across multiple sectors and scales of operation have to cooperate to enable local energy flexibility. PED Hillevåg examines ways to enable such synergies.

The largest point source carbon emissions at the urban scale often come from industrial processes and are hard to abate. Reusing some of the process energy in sync with local energy demand, switching to cleaner sources, and coordinating across sectors to tap into energy as multiple vectors (e.g. electricity, heat) all present necessary options to explore for PED development. These endeavours require public-private partnership models in order to enable collaboration across sectors to achieve ambitious urban mitigation targets.

The pace of research and innovation as well as the municipal interest in achieving ambitious urban climate targets follow a different timeline and agenda than corporate actors with ongoing large-scale industrial processes. This introduces a challenge for PED Hillevåg planning to retain relevance during the three-year project timeline, given the need for industrial partners to make long-term investments in infrastructure on a short horizon. Political decision-making on urban development plans in the neighbourhood introduces additional uncertainties with limited scope for knowledge to inform action.

Finally, Budapest in Hungary has two pilot areas within the Energy4All project. The first site, implemented by the Budapest Municipality, is connected [LP1] to the local pilot of Ascend, an energetic refurbishment and transformation of an old school building at Megyeri ut into social housing units. The aim is to make the building an integral part of the locally developed Positive Clean Energy District (PCEDs), and to accelerate its development. The site will be upgraded with PV installations, establishing charging points for municipal fleets and public users, in sync with the development of “school streets”, deploying traffic calming measures on school roads etc., and creating citizen-centric solutions with the support of the recently established Climate Agency. The concept of Positive Energy Districts (PEDs) development is relatively new in Hungary so the Megyeri Út School is a pioneering project, serving as an integral element of this area and possibly an energy community in the future. With its PV installation and energetic refurbishment, the building can function as a centre for the future local energy community, and draw nearby public and private buildings into the initiative.

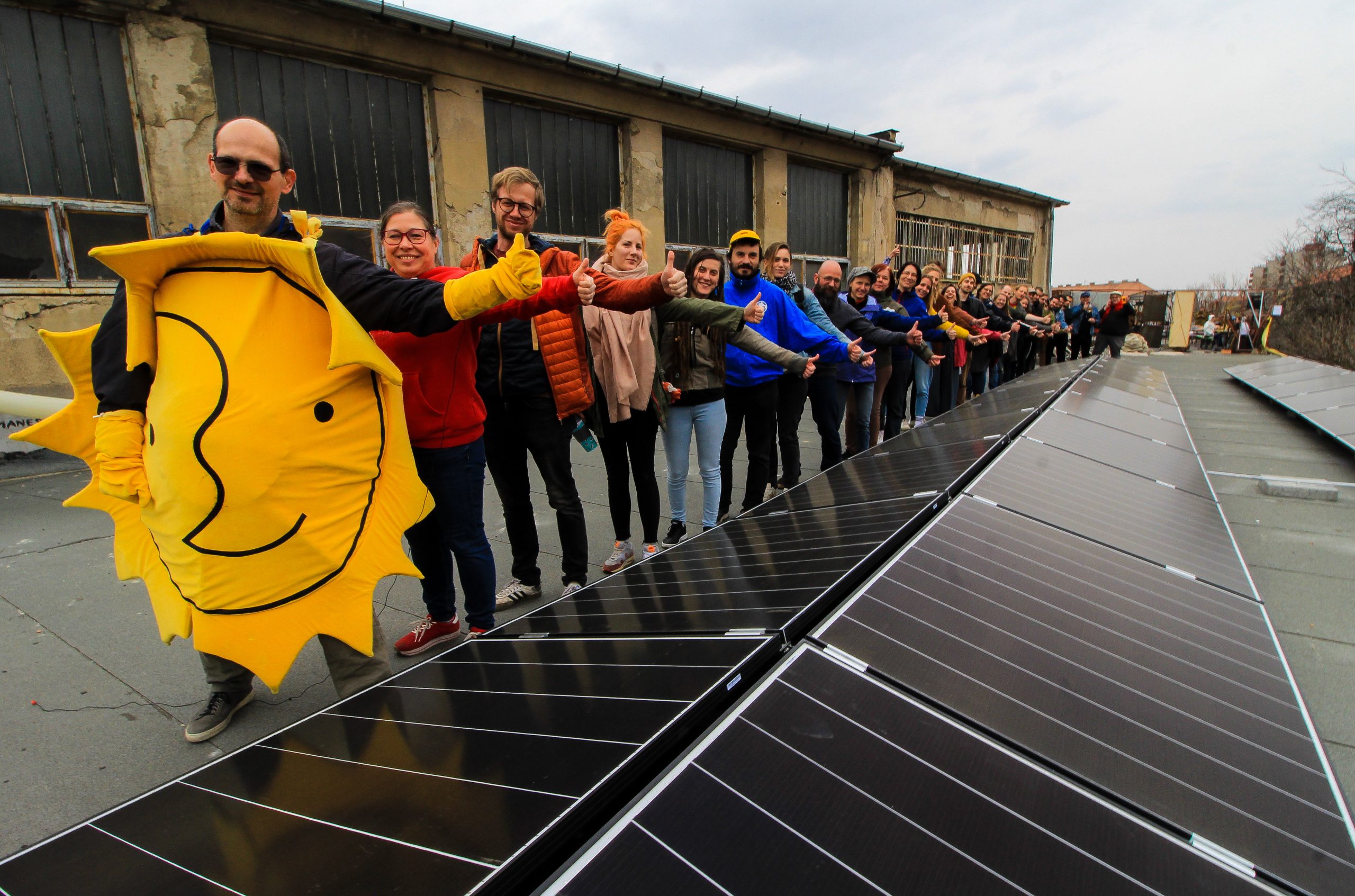

The second case in Budapest is the Kazán Community Centre, a collectively-owned building with an emerging energy community, to be upscaled during the project. Kazán will further develop its existing energy community project by exploring behavioural change around energy consumption and production, and by co-designing with local stakeholders a methodology to improve the ECs/PEDs performance. The aim is to have a collaboratively decided energy retrofitting plan, to enhance the energy efficiency of the building and to maximise PED performance while taking advantage of the 36 kW solar panels already installed on the rooftop.

The Kazán Community Center gives home to several organizations: a community daycare, workshops, a community radio station and media outlet, as well as offices for civil society organizations. The community has already had a functioning and established collaborative management system that was very beneficial in the establishment of the energy community management structures as well. The whole management of the building is based on the pillars of solidarity and co-ownership, so the community energy initiative also shares these values. For example, during the energy crisis, Kazán have tried to create a just system of sharing the burdens of the high gas and electricity prices and also connected to this, the democratic management model is characterized by high adaptability, allowing to reduce gas consumption by 50% during the energy crisis. The main challenge of this pilot is that due to its member organisation status and the main principles the community tries to achieve on the basis of affordability, it faces problems when it comes to financing capital intensive investment-needs, such as energy efficiency renovations. As the building hosting Kazán is a post-industrial site, there is a need for retrofitting some of the building’s infrastructure, and furthermore, the disadvantageous and fluctuating regulatory framework around PV installations and energy communities in Hungary has made the PV connection to the grid very challenging.

Challenges and perspectives

Despite the wide range of differences amongst the various case studies of the Energy4All project, a number of similarities may be identified.

There are great regulatory and policy barriers due to the different regulations across EU member states, which create complexities for energy communities. Furthermore, “energy community” can mean different things in different countries, hindering their legal status and access to support, and the bureaucratic processes and grid limitations can delay the integration of renewable energy sources. Then there are financial constraints, due to the fact that setting up renewable energy infrastructure requires significant upfront costs, often challenging for low income communities, which may struggle to secure loans or investments compared to larger energy companies. This is especially important if we consider the revenue uncertainty given by the fluctuating energy prices and market volatility that can impact the financial stability of the energy communities.

Integrating renewable energy sources into existing grids can be technically complex and require skilled personnel, as well as managing fluctuations in renewable energy production, as this necessitates effective energy storage solutions. Furthermore, reliable digital platforms are essential for energy sharing and management, but they may require investment and technical skills that not all communities have. For all the above mentioned reasons it is fundamental to ensure social engagement to foster a strong sense of community, providing all information necessary to overcome a potential knowledge gap, as well as ensuring fair participation and benefits for all community members to avoid social tensions. These challenges are exacerbated by the market dynamics, as this offers limited opportunities to sell surplus energy, therefore reducing the financial viability of energy communities that already struggle with the fluctuating energy prices that can impact their profitability. All of this results in energy communities often competing with larger, established energy providers, creating an uneven playing field.

This is why we need to strengthen communities to tackle energy poverty, develop territorial projects and experiment with new business models for social enterprises as well as industries. Our vision is to create city-wide networks promoted by public administrations and co-managed at local scale by private and civic stakeholders, where energy communities are a pilot towards a democratic and ethical energy transition.

Article by Daniela Patti, Eutropian