We all have beloved public spaces – spaces where we feel safe and comfortable, places we like to come back to, places where we can let our children play freely and, why not, places where we adults can play as well. Yet, as our cities grow bigger and bigger and get spruced up, truly memorable and valuable public spaces are scarce. In fact, since the mid-twentieth century, new residential areas and public spaces have been designed to accommodate an ever increasing automobile traffic, with a huge impact on all other users of public space. Non-drivers have different needs and expectations which are very rarely met, as too many public spaces in our cities are undervalued and neglected. Placemaking was born as a response to this phenomenon, initially in the USA, but then expanded to societies in other continents as well.

Placemaking has more than 40 years of history in Europe with Barcelona, Copenhagen and Amsterdam leading the way on the European scene. During the past decades, available placemaking tools have evolved from small interventions to strategies that affect entire cities. These approaches can be used to address urban issues such as lack of public spaces and neglected neighbourhoods, just to name a few.

International collaboration among placemakers is crucial to generate greater impact on the urban fabric of our cities. PlaceCity is a project aimed at advancing the European network to give a deeper insight into how placemaking practices can support urban planning and revitalisation processes.

In Oslo, the local teams participating at PlaceCity revitalised and opened up a schoolyard in a priority district with active student engagement, while creating training and extra-curricular collaboration opportunities for the students. In Vienna, the teams developed solutions in a peripheral district to activate a stagnant public life and invite promising practices to show what public space could do for the citizens. PlaceCity collects and tests placemaking tools, while long-term strategies are shared on an open source basis on the platform of the NGO Placemaking Europe. The partners of the project meet frequently to further develop their pilot cases, to exchange and participate in public conferences, webinars and events in order to share their findings and involve other placemakers in the process.

Winter placemaking in times of pandemic crisis<

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, public life and public spaces are facing very difficult challenges. The PlaceCity teams are presently looking for stronger collaboration and exchange with each other in order to find collective solutions to pandemic-regulated public realms during winter.

In this article we explore three inspiring approaches to re-thinking public spaces, based on presentations at the webinar “Placemaking Pils” organised by PlaceCity project partner Nabolagshager.

The “Subvertising Norway” initiative from Oslo brings the question of ownership and rights to public space to the forefront. Helsinki’s “RaivioBumann” shows how technologically playful design can bring joy in the public space even in winter times. Grätzloase adapts non-commercial public spaces to winter conditions in the city of Vienna for humans to mingle and connect.

Piece dealing with housing rights in Oslo

Photo (c) Giulia Troisi

Subvertising Norway – replacing advertising with guerilla art – OSLO

James Finnegan is based in Oslo and works with Subvertising Norway, a smart mob of artists, activists and designers that practice adbusting as a form of civil disobedience to exercise their democratic rights as citizens and draw attention to the way public spaces are used. Subvertising Norway seeks to reclaim public space by replacing outdoor advertising such as on billboard with though provoking art with contemporary social messages.

All subvertisers (with Adbusters from Canada being the forerunners since the 1990s) share the same goal: to question who has the power or authority to communicate messages and create meaning in public space. Many of them are open about their actions, even though technically what they do is illegal. However, they believe their action is indeed necessary – and therefore lawful in terms of natural law, as it prevents greater crimes such as abuse of power, exploitation and unfair profit.

Anti-green washing campaign targeting Equinor – a collaboration with a local youth environmental organisation called NaturalDom in Norway who were suing the state for continuing to drill in the Arctic. Photo (c) Giulia Troisi

By acting on the basic principle that the visual realm in public space belongs to everyone, Subvertising Norway thinks that no one should be able to own it. Public space should be a forum for dialogue, debate and exchange of ideas. Briefly, everyone should be free to participate in public space, not only companies and organisations that can afford to rent our attention.

Outdoor advertising is very different from other types of advertising: while in the digital world, on TV or on paper you can always look away, change channels or switch off, when it comes to outdoor advertising, you have no choice, you cannot avoid it, nor can you unsee it.

Researchers have proven that advertising works powerfully on the subconscious level, without you needing to pay a high level of attention – you can actually recognise brands without physically recalling seeing an advert. This is why advertisers and companies pay huge amounts of money to put their messages in these public places, where everyone sees them. Billboards represent some prime real estate. For this reason, there is concern about the effect that advertisements have on our minds, society and culture in general. Both in existential and placemaking terms, subvertisers feel they have to do something about this. This winter, in which most of us have limited access to arts, culture and community activities, the use of public space is more crucial than ever, therefore advertisement practices in public space have to be questioned and adapted to the current situation. Subvertising Norway shows how the collective discourse can continue in the public realm, even if apparently silently.

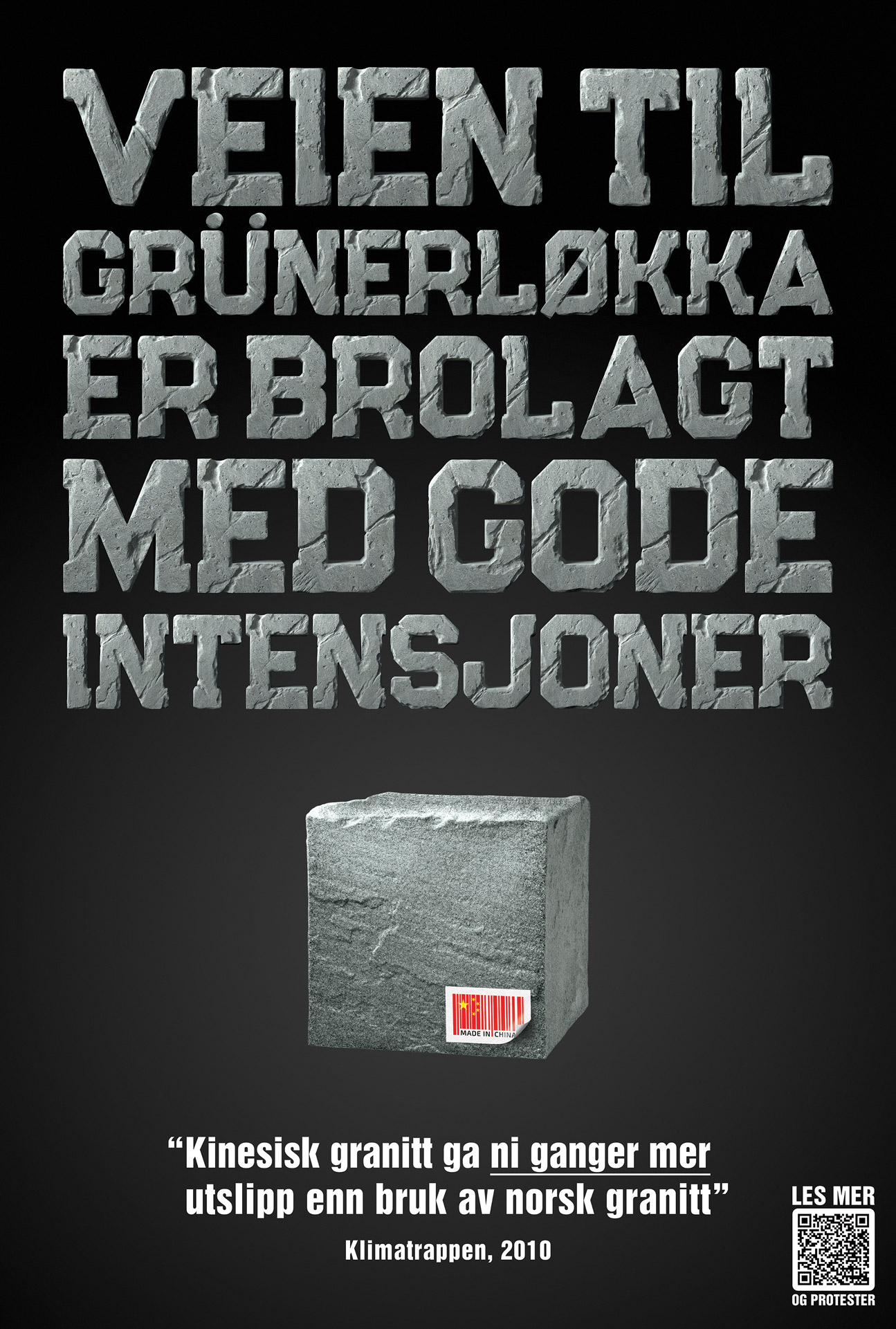

Grünerløkka was once a workers’ district, now a trendy, hipster shopping and leisure area in Oslo. The subverted ad draws attention to the fact that stones were being flown from China to Norway to repave the streets of Oslo, obviously with a huge CO2 impact.

Modifying ads is also known as “culture jamming” – that’s when you take a pre-existing advert and you subvert its message or meaning. This is the type of subvertising that companies dislike the most: one thing is to take an ad down and replace it with a pretty picture, another thing is to subvert their message and their brand and play with that.

Another form of subvertising is when you take down an ad altogether and replace it with a work of art. Subvertising gives the opportunity to reach out to artists, designers, illustrators and a whole wide range of people who all bring their contribution and personal vision to disseminate a better understanding of subvertising, its sociocultural, political and economic values while raising awareness about the ubiquitous role of advertising.

“In Covid times it’s even more important to find ways to unite people and bring them together, physically or online, and encourage them to shape the city in ways that exist outside of established power structures.” James Finnegan, Subvertising Norway.

As a result of the increasing public debate on human rights, housing rights and the ecological crisis, the past years have seen a boost in reclaiming public spaces from commercial use for societal messages. Subvertising examples from Oslo illustrate very well the public criticism towards big businesses with poor environmental and ethical credentials.

RaivioBumann – developing public space to be more inclusive, interactive and fun – HELSINKI

Päivi Raivio is a Helsinki-based artist and designer with a mission to rethink public places using urban design, placemaking and public art methods and tools. Along with Daniel Bumann, she is one of the founders of Helsinki-based RaivioBumann. They are active in urban design, public art and placemaking projects which have a direct focus on people’s participation, thus acting as a medium between a physical space, people and their interactions. Their set of values includes better interaction between people and places, inclusive cities and making public space a more fun and democratic platform.

RaivioBumann works with researchers, architects and municipalities but their background is in set design, public art and community art – all aspects that can be seen in their approach and projects.

For instance, one of their exemplary works is kohtaamiskioski (“encounters kiosk” in Finnish) was set up in a newly developed area in Helsinki which doesn’t yet have a sense of community. This is the first of a series of kiosks that aim at becoming pleasant meeting places that can serve as a tool for socialisation.

Noticing that cities are dotted with lots of spaces where people are only passing by, RaivioBumann wants to create “friendly obstacles” in order to make people stop and observe what’s happening. Their Bright Swing focuses on winter and on the darker seasons in general. Based on the idea of interaction and environmental sustainability, they developed a way to combine light, movement and play while producing electricity off-grid. Its lights get powered to 100% through the energy created by the movement of the user. The light swing encompasses all these aspects, becoming a playful structure for public spaces promoting sustainable thinking and playfulness. This creation was also installed in the Helsinki City Museum courtyards during Lux Helsinki, the annual light festival.

Grätzloase – terraces in the streets to mingle with friends and neighbours – VIENNA

Eva Braxenthaler is part of Grätzloase, a Viennese initiative that supports neighbourhood groups to implement creative ideas in public space.

Lot of their spaces are parklets – installed mostly in parking lots – which are non-consumption-oriented terraces, free for everybody to use, with nothing to buy or sell on them. In Vienna, the municipality allows placemakers to turn up to two 15 square meter parking lots into parklets. Grätzloase has built 220 different parklet locations all over the city in the last six years, mainly in densely populated areas, because this is where parks or meeting spaces for free public usage are generally more needed. More than 2000 events took place at the parklets and around a thousand Viennese citizens have transformed parking spots into spaces that were used by everyone. Examples for the use of these lots include parklets where people can repair their bike for free (with tools provided); terraces with benches and tables where people can get together, get to know one other and hang around; or a pool that was installed in one of the parklets in 2019.

While the program formally ended in December 2020, the presence of parklets has been extended as the municipality realised people need more space outside during the pandemic. While there are no events taking place in the parklets due to the Covid restrictions, the bike repair stations will work over wintertime as many people in Vienna switched to biking instead of taking cars or public transportation – otherwise they will use the space to meet and chat. This is good news for the organisers, as they now have the possibility to leave the parklets on the street, as the most expensive part of putting up these parklets is their storage during wintertime. Grätzloase also supports those people who want to build their own parklets with implementation advice.

More and more people are showing interest in building these parklets. The soft and slow modification of parklets enhances their “personality” according to the citizens’ spontaneous contributions. For example, it allows residents to put plants around the parklets and get together with neighbours and share mulled wine. The Grätzeloase initiative plans to continue decorating the parklets during winter and refurbishing them for the needs of citizens with an inspiring approach to test new functions in a pop-up manner. While they offer citizens a creative and social outlet, they also illustrate how fast, easy and cheap such adaptations can be.

“So far, we built 220 different parking locations all over the city, mainly in densely populated areas, because this is where parks or spaces for public usage are generally missing.”

Eva Braxenthaler

2020 and 2021 are challenging us in all spheres of our lives. In a time of social distancing and harsh regulations, these parklets can alleviate the stress while continuing to create supportive spaces for everyone in every season. In the midst of a health and economic crisis, Grätzeloase shows how even temporary design can improve our daily lives and activate our collective creativity, especially during this winter pandemic.

Further inspiring placemaking approaches can be found on the website of the Placemaking Europe network. The collaborating teams also created Winter & Pandemic Proof Placemaking in Europe Open Calls to exchange and highlight promising practices.

If you have ideas and solutions to combat winter challenges in a pandemic situation, feel free to send us your examples. We will be happy to share them with the PlaceCity team.