With the announcement of the lock-down due to the COVID-19 people in many cities literally assaulted the supermarkets to make sure they had enough stock at home to survive the quarantine in case of food shortage. Despite this being the result of a collective anxiety due to the extraordinary situation we are living, it clearly lighted one of the weak elements of our system: access to food. In fact, in times of prosperity we have been used to the fact that any type of food could easily reach our nearest shop at a relative cheap price in hardly any time even from the most remote locations. The discussion over food sovereignity was often relegated to a limited number of highly politicised communities advocating for a rethinking of our production, distribution and consumption systems. But with the EU borders shutting down, making imports harder, with people being worried to work in the field, making the available labour force for flirt and vegetable picking scarcer, short food chains have regained prominent attention.

Episode #2: Food production and distribution systems

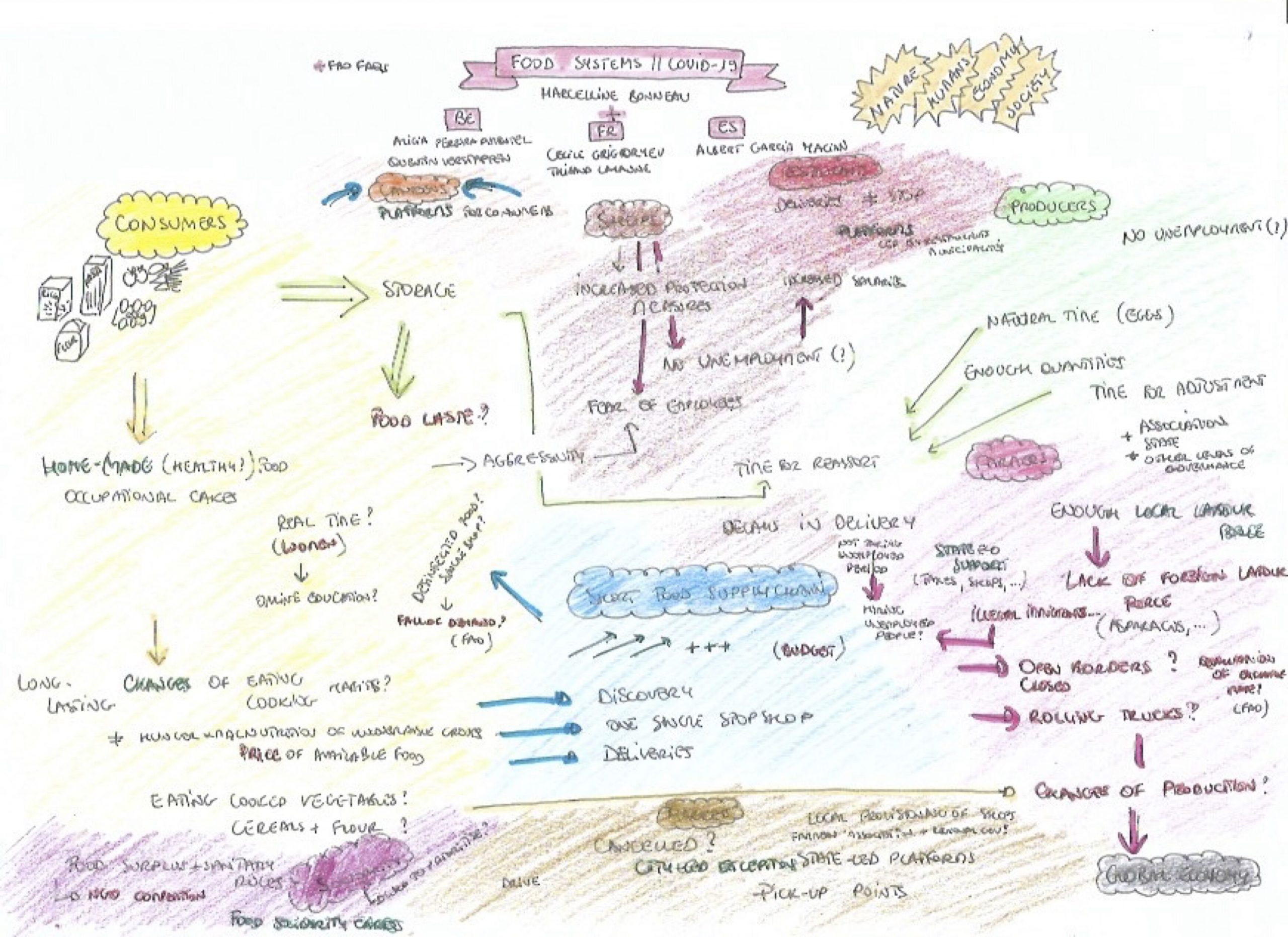

Last Friday 27th March 2020 we held our second episode of Cooperative City in Quarantine where we invited experts on food production and distributions systems from different European cities to share with us their perspectives on what are the challenges we face during COVID-19 in relation to food and what are the emerging practices we see.

We invited Marcelline Bonneau from Bruxelles, director of Resilia Solutions and expert in various EU as well as local projects on food systems, Igor Kos from Maribor in Slovenia, part of the WCycle Institute and working on the Urban Soil 4 Food UIA project focusing on circular economy and Francesco Paniè from Rome, part of Terra! Onlus that focus on transparency within our food system.

The learning points of our discussion:

It’s hard to imagine how COVID-19 will affect our food production and distribution systems in the long run, yet we can draw some learning points.

- We need to ensure food sovereignty and therefore that we are able to produce our own food, as much as possible;

- It is essential to ensure fair labour conditions to workers in farms to those planting and picking our food;

- This is the opportunity to establish and innovate our public food policy, connecting producers and consumers through a publicly owned infrastructure of farms, distribution firms, markets, etc;

- We need to ensure access to healthy food also to poorer citizens, this can be supported through vouchers but also by establishing public community gardens;

- The rise of food delivery offers the opportunity for restaurants and delivery people, together with consumers, to cluster their requests and ensure fair working conditions and share of the profit from delivery food firms, such as Deliveroo or Just Eat.

What are the main challenges you see in the present moment?

Marcelline: We have been in full lockdown for ten days and there has been a rush to the supermarkets to buy most basic goods. Currently, the whole food system is being disrupted by the COVID-19 crisis and containment. Our eating and consumption patterns have been modified, e.g. an increasing number of people go and buy from the local shops, in short food supply chains (doubled or tripled in most cases). People cook (healthily) at home. Yet, won’t this add to the mental load of women? Do they actually have time for it as in most cases will be the ones in charge of the home and education or children (in addition to working from home)? Will these become new long-lasting cooking and eating habits? At the same time, FAO underlines the risks of increased hunger and malnutrition of vulnerable groups. It can be so, for example, as the rush to food in supermarkets has concerned primarily cheap food, making it unavailable to those in need. Competition to access food surplus is fierce between charities. Discount lunches in public canteens are not available anymore, food aid has had to adjust its practices. Those the most at risk and isolated cannot go and shop anymore.

Igor: In Slovenia we are not in the situation of full lock down as in Italy or Belgium, we are still allowed to go out but self isolation measures are encouraged. We do not seem to face food shortage issues at the moment, there is enough food in the stores, but obviously there was an anxious race to the supermarkets to buy up food in the past week. In Slovenia the government suggested specific times for people to go to do the shopping, especially for the elderly, in order to ensure that people don’t all go at the same time.

Francesco highlighted how in Italy there are currently great challenges in relation to food production because most of the production food system is based on migrant workers. Currently these people, already because of the new migration law, have now stopped working in the fields because of the COVID-19 emergency. This could mean that there will not be enough people picking and planting our food this year. Furthermore, these people work in terrible conditions, often illegally, and in unhealthy living conditions, as they live in slums with no water, under great risks.

What is happening on the ground?

Marcelline: In the retail sector, intermediaries still need to adjust to quantities being asked by shops. Shops have adjusted their ways of working in, including sanitary and distancing rules. In most countries as well, these are necessary sectors and sellers don’t have access to financial support for unemployment: they (sometimes) need to support aggressive customers and (sometimes) face their own fears of being contaminated. Yet, shops make their best figures: as such, supermarkets in Spain have raised salaries by 20%.

Restaurants are closed. City or private-led platforms put them in contact with consumers for delivery or pick-up, with similar approaches for canteens and some markets. Other markets, in Spain and France, get exceptions for being opened.

Igor: Here in Slovenia all not necessary shops have been closed down but food shops are still open, despite their opening times have been reduced. The number of people entering the shops at the time are limited, with a guard at the entrance, which ensures that people don’t crowd especially at the counter. The farmers’ markets are open, even though not all stalls and not for the whole time. Even the neighbouring municipality to Maribor announced just yesterday that the farmers’ market will be open on a regular basis. This means that producers can sell their products and consumers can buy, according to the social distancing measures, even though these are more flexible in the market as this is in the open air. To my knowledge, there is no shortage of food at the moment, maybe some specific products.

What is ahead of us?

Marcelline: In light of the Farm to Fork strategy (currently postponed), producers have to adjust although smaller farms feel confident about the next few months, larger ones fear the lack of (foreign) labour force, for example usually hired for planting asparagus or strawberries. Attempts have been made to legalise illegal immigrants (in Spain and Italy), yet, with no success.

COVID-19 does not affect negatively nature related to our food system. It affects people and the economy. Nothing will be the same after the lock-down. Yet, the food system cannot change over a day. The postponing of the Farm to Fork Strategy shows the delays in the strategic levels. As such, it is crucial, more than ever, that we plan and implement the transition now, for it to be effective as soon as possible.

Igor: In Slovenia we have the problem that we are not self-sufficient in some areas of food production, for example for food and vegetables we are only 50% self-sufficient, which means we are dependent on imports. This might be a challenge in the near future because of the closing borders. Therefore, under current conditions the local food producers are being supported and the City has published a list of the local farms so people can get in contact with them to buy the food directly or by using the Inno-Rural app developed within the Urban Soil 4 Food project. So some good is coming out, as this allows to reduce the damage for farmers. They, for the moment, are not facing problems for the labour, as in Slovenia we are less dependent on foreign workers than Italy, for example. Many people are relying on community gardens, which is not only a healthy option, but especially allows the less wealthy ones to access affordable and healthy food.

Watch the full episode

Marcelline Bonneau would like to thank the many people who shared their insights in preparation for this discussion: Alicia Pereira Pimentel – Molleke – and Quentin Verstappen – Almata – in Belgium, Cécile Grigoryev – farmer – and Thibaud Lalanne – BioCanteens – in France, Albert Garcia Macian – Mollet de Vallès – in Spain.