Plateau Urbain is a temporary use organisation in Paris. Established in 2013, it examines the possibilities of vacant spaces in the city, bringing together property owners with a diversity of tenants. Together with the temporary housing organisation Aurore and the architecture collective Yes We Camp, Plateau Urban was a key actor in reactivating a former hospital site in the 14th district of Paris, with hundreds of temporary housing units combined with hundreds of associations and small companies. Today Plateau Urbain manages several buildings across the Paris region.

“Temporary use is an urban laboratory, a genuine way to incubate and experiment”

What is the origin of Plateau Urbain?

Plateau Urbain was born in July 2013 as an association based on one concept. Or rather, we base our work on the fact that on the one hand there will always be structural vacancy, because empty buildings are a by-product of urban processes, and on the other hand there is also an evolution in the modes of creation and work. This is partially a generational approach that results in the evolution of demand. And then, there are what we call project coordinators, whose work mediates between economical actors and cultural associations, providing insight into their different needs.

Do you position yourself as such a project coordinator?

The main idea is to make people meet: the owner who can cover the expenses, keeping in mind both financial and property implications, and the people who can pay (not a lot) within a fair deal for using an empty building. We facilitate the negotiation. Obviously, there are several stages to this process. The first step consists in letting the project coordinator assess the situation, so that they can understand if there are obstacles. There could be lack of real estate-oriented culture, lack of visibility, there could be misunderstandings regarding property and decision-making or the fact that there are too many questions from both sides. Other than that, sometimes the financial expectations of the owners are far from the actual conditions of their property.

How did you start working on such arrangements?

Here in Paris we began with organising temporary use for a few small-scale, commercial events. As we had been working with a diversity of partners, including from the social and solidarity economy, and we got an award for this, Aurore, one of the biggest organisations for social action in France, approached us. Aurore was managing a project called “L’Archipel” (Archipelago), to be located inside an old building complex with a chapel. The chapel was used as a space for cultural events and other services such as catering, while the rest of the complex was used for temporary housing and other activities, which was a very original approach from Aurore. We have been brought into the project to help them find people to rent the spaces, which was part of our work. After this, we were invited to work on another project of theirs called “Les Grands Voisins” (The Big Neighbours) which was a turning point for us. There we speak about 600 temporary housing places, 200 organisations, 12000 square meters for accommodation purposes and 8000 square meters for the activities, so this makes it one of the biggest temporary use projects in Europe.

What is your role in Les Grands Voisins?

We help in the field of real estate strategy, managing methods and other technical aspects of management that are better not to ignore. Technical questions come first, even before the process and the design. But once the technical aspects are clear, everything else can follow. The rest, in our view, in terms of the building’s use is open programming: we did not invent this expression but completely recognise ourselves in it. It is the idea that since buildings can host activities of all kinds, we must combine them in a smart way. This is what we do here and elsewhere. The craftsperson, the start-up or other activities of different degrees of maturity can benefit from this proximity and can establish connections without heavy investments into facilities of incubation.

What competences did you need for this endeavour?

Competences in Plateau Urbain vary, but by default, we all have a degree in urbanism. Then there is knowledge of real estate, planning, transportation, fund management and development. The rest is built around the needs of a growing organisation with roles like coordination and communication. This is briefly the structure right now: we are a group of fifteen, one and a half years ago it was only three of us. We are about to become a cooperative where we can bring together all these competences. We are all involved in the daily operations, but we also rely on a circle of external experts and friends who supported Plateau Urbain right from the start. We meet once a month for updates and to discuss priorities. Last but not least, there is a circle of partners, the owners of the buildings, the communities, the collectives and other collaborators who take part in the projects, including specialists in terms of re-use, real estate market innovation, digital management and such.

Are you working on making a permanent model out of temporary uses?

As for the organisation, we do not exclude the possibility of raising investments, but not with a speculative purpose. We want to become permanent, make a 5-year plan and refine our approach towards the interaction between temporary and permanent. We realised that creating an ecosystem is the key. Many times, people opening “new activities” end up opening “new offices,” and later they realise that it is not what they wanted to do. Most of the times they lack specific networks and technical or financial know-how to open accessible and affordable spaces that are badly needed here. We want to inform, systematise, automatise, facilitate temporary use. We want to keep it as a reflection on real estate but also asking what can we learn from it. It might be that these learnings will support lobbying, theoretical reflection or competitions, anyhow, this reflection is important for us.

What revenues can assure your work in the long term?

These are aspects that we are still testing, there are several scenarios. At the moment, our budget comes from the owners and municipalities who pay us for a preliminary study, the management, etc. As for the management of spaces, there are different ways. We can create specific associations in order to make the revenue stay in the place. It is convenient for us because this would ideally allow us to activate the project and to make the renters manage it without it being necessary for us to physically be there all the time. In reality, we are testing this format but we still remain involved in the management. It is not a bad method: it does not drain you of all the energy and it allows you to still keep an eye on small everyday problems, such as the shared spaces where there might be tensions, so that you can intervene and solve the problem before the ambiance of the whole place suffers the effects. Yet, this way none of the budget would go to Plateau Urbain. It would be a good idea, for example, if every temporary use project contributed to a metropolitan investment fund where the budget excess for the management of a place would be allocated to this structure and would help initiate new projects, like a solidarity fund. The question is how to administer this, because it could be a lot of money. It would be great to meet other organisations who work with a similar logic, identify ourselves a movement and share these funds according to specific criteria.

At the moment, when we manage a place we try to optimise it: we have a budget for the basic operation, for the running costs, the presence of an intendant at the site and the construction of common elements because we know that it is important to have events or shared spaces. But if there are people who are interested in making film shootings or events, we will say yes, because this brings some money to Plateau Urbain. It is an old-fashioned way of financing a temporary use that we do not exclude. It depends on the spaces that are we are offered: in some spaces it is impossible to organise regular activities, but we can accommodate art events or film shootings that might bring in good money. The problem is the initial investment: we have difficulties in convincing the owners to designate tens of thousands of euros as initial investment in a building. In the case of Les Grands Voisins, Aurore made this investment.

How did it work in the case of Les Grands Voisins?

It is a very particular arrangement: Aurore represents a third of the revenues, but they are taking all the risk. In fact, the board was a bit stressed about it. The money is public, yet it is not directly linked to this project. It is part of a fund for temporary housing, the same fund that is otherwise used in single buildings, usually in another part of the city and in a better state or for the construction of new buildings.

Aurore receives €2 million per year, 900,000 for the temporary housing, and the rest from the rents. There is also the budget of Yes We Camp that represents a €1 million. With these more dynamic resources, a different economic model could have been done but this choice was not made. The questions is: if beer, in a classic way, the fuel for this temporary project, what does it pay for? Does it pay for more beer, more development, more openness towards the public? Because there are many groups here, many people, a lot of fixed costs. Or these revenues allow investment in the buildings, or in social aspects? These are the questions for the future or for other configurations.

How do people accept the temporality of a project like Les Grands Voisins?

This is the big question of 2017 at Les Grands Voisins. First of all, there was a very clear base agreement stating the exact duration of the project. We never changed its dates because we think that prolonging the contract every 3 months or so would be a disaster. People would not actually find it easy to move on. So there is this pedagogical element beforehand and then we have set up a forum – not exactly a discussion forum, but an informative forum telling everyone that the project ends during the month of December. It will not last longer, it will not be shorter. We want to be very clear and also very cautious with this. A survey has been launched regarding the “next step” for the people who were part of this project. We know very well that about a third of the associations that took part in this project were born within its framework, and probably they are not ready yet for the traditional market. We hope to have other proposals for them soon, but we cannot promise anything. We are sure that if we open a new project in the South of Paris, but on the other side of the Périphérique, we will lose 70% of the people. Not everyone thinks in the Grand Paris. Within the dialogue we have with our tenants, we also try to train them about the specificities of this type of real estate: these are not residential buildings, the power relations are different. We tell them how these spaces work and we give them tips. Most of the people understand but there are always some who enter in resistance or anxiety about their future. Others are extremely curious but their economy is very precarious and still depending on a temporary ecosystem.

Do you already have ideas for new sites?

Launching a project rarely requires more than 3 months. An owner shows up and tells us that they have a disused building they would like to repurpose. We generally always accept or refuse the project within 3 months because these things must happen fast – if it takes you 6 months to decide regarding a program lasting 1 year, it does not work. And we are not responsible for the relocation of activities here. We prefer, for many reasons, to simply encourage movements. For example Porte 14, where the tenants have become friends although they do very different things, have began planning to rent or even buy a building together because they understood that the can work very well together and for them it is the desired continuation of the project. I know that Aurore is trying to take some barracks, hospitals and similar buildings because they have proved their ability to manage such structures at this scale in a spirit of responsibility. In these projects, they will probably reproduce this mixed-use model, even though opening these spaces for the public is not always appropriate. Les Grands Voisins is at a very central location, but if the next project is in Neuilly-sur-Marne, one hour away from here via RER, chances are it will work differently. However, the basics are all there: social dimension, variety of activities and the engagement towards the public. These are the core elements to reproduce, or better, to develop, as it is not Aurore, Plateau Urbain or Yes We Camp who will do all the temporary uses there. We see that there are many collectives, with different backgrounds but inspired by our experience, whose inspiration comes from our approach, yet they adapt it to their territory.

What are your other projects?

Besides Les Grands Voisins, we are now working on five more projects scattered around Paris and its outskirts. They vary between small, self-managed residencies covering 100 square meters and other mixed projects similar to Les Grands Voisins but not accessible to the public, 5000 square meters in the fifth district where about 15 people live in temporary housing in addition to about 30 organisation using that space to work. We do all this with Aurore who are operators of the housing component. Housing is an important element of the programme in these spaces as it responds to the question of who has a place in this city and at what price. We are slowly evolving toward new solutions, or better, we are studying new solutions, because people often have limited knowledge about their property, or they cannot identify strategies to manage buildings: there is a real demand from the side of property owners to have clear answers. We address traditional actors whose logic needs to be integrated: promoters, investors, public administrations. I have to underline that it is easier for us to work with private interlocutors than with the public sector: they are just much faster.

Is the argument for temporary use the same towards public and private owners?

There are several argumentative layers to this, depending on the people we are dealing with. There is obviously the defensive approach: “If you have to hire guards and watchdogs for surveillance, it is going to cost you thousands of euros per month. Multiply this amount for the number of months the building will remain empty and all your money is gone.” It is a reflection that resonates better with the owners of small properties. On the other hand, and this is a positive point, we have already proved with our past activities that this methodology creates an urban laboratory, a genuine strategy for incubation and experimentation around new ways of working and new spaces of work. We look into how to programme activities in the future in order to help people use a temporary phase to build and test a project, before finding their place in the traditional market. In the case of Les Grands Voisins, we have conducted a study on behalf of the developer that will redevelop the area to understand at what price and with what modalities we can create workspaces to accommodate this kind of economic tissue.

How do you select your tenants?

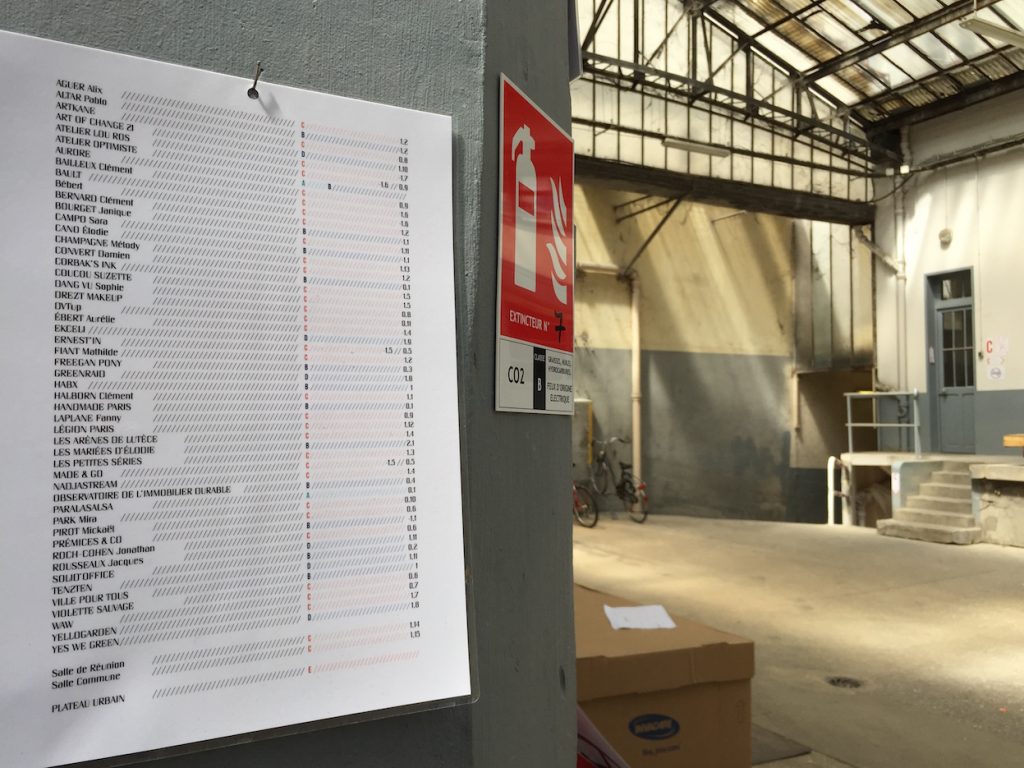

We know that there are a lot of actors we do not know yet in an area, and if the selection was made through cooptation it would not be fair. We do it as pragmatic and equitable as possible. When we launch a call for participation, the idea is to mobilise a maximum number of projects and then devise the identity of the place. We are not going to say “this is going to be an art project so we will only search for artists.” We obviously organise the actors we work with into modules.

How do the features of a specific building limit your options?

Like all organisations working with temporary solutions, when we face an empty building, we ask ourselves three questions: How long is the building going to be available? How much will it cost to do there something? What can we do inside it? In France, public access to a building is understandably very regulated, and this is often where have to negotiate. But even before this, simple questions emerge about the safety of the building, if it contains asbestos or lead, issues that we have to integrate in the reflection. Sometimes the structural conditions of buildings have deteriorated to such a point where they are no longer usable and would require too much money at the beginning, risking to never pay back the investment. We can always imagine that an owner is willing to make a significant initial investment, but we try to argue for a shared effort where all actors can benefit, not necessarily in economic terms, and avoid that the public perceives temporary use as subsidised projects where money is necessarily lost.

Are property owners open to these kinds of arguments?

There has been, at least in France, a kind of a “Small Ice Age” at the end of the 1970s, when some temporary occupations were very much covered in the media at the moment of being endangered. This created a derive of the perception of what temporary projects can be: the general public’s perception of these projects became associated with squatting, and this caused a wave of prejudice towards initiatives like ours, which are clearly very different. On the other hand, there have been several good examples, like the 6B in Saint-Denis that showed that it was possible to make temporary use work in an intelligent way, that it was possible to work with developers and that temporary use was an added value at the level of the project. We have strongly benefited from these past experiences as well as from temporary events or urban festivals we organised.

How did you see the approach of the public sector changing towards these ideas?

We are lucky to have many politicians from the Municipality who are really interested in all kinds of innovation, and they see these temporary projects as elements of innovation. Now there is real interest around this topic and things are becoming easier. Of course every project has its own hardships, but people are trusting our initiatives more and more. Also, allegiance towards particular political parties may be important, but it is equally important not to become too dependent on it. Our work is not political, and even though sometimes we have to make partisan choices, we are in fact “transversal.”

Interview with Jean-Baptiste Roussat on 12 May 2017

UPDATE:

According to the original plans, Les Grands Voisins closed in December 2017, and will reopen at a smaller area in March 2018.