Locality is the national network of ambitious and enterprising community organisations, working together so neighbourhoods thrive. They support organisations to work effectively through best practice on community enterprise, community asset ownership, local services contracting and collaboration. In a continually evolving landscape, Locality supports community enterprises to develop their organisational and business models to survive and grow.

“Community groups have fought hard to maintain services with new models of community ownership and management”

This interview is an excerpt from the book Funding the Cooperative City: Community Finance and the Economy of Civic Spaces

How would you describe the community organisations you work with?

The most important defining factors of the organisations we work with are that they are truly accountable to a local community, so local people are actively involved in communicating both the need for local services or activities and involved in how the organisation is run. This could mean that there is a certain percentage of local residents on a governing board for example, or a membership model that gives voting rights to local people. We also feel that organisations that deliver a number of different services to a community are better placed to respond to the complexities of community need than those that offer only one service.

Finally, our members are characterised by their enterprising business models – this might involve delivering contracts from the local authority, trading income from selling products or services (room hire or space for wedding hire for example) and some grant income. This diversity enables organisations to survive as funding environments change and to continually adapt to meet community need. The turnover of our members varies considerably, from around £9 million to £50,000 and some have been serving the community for over 100 years whilst others have emerged more recently to meet new needs in the community.

How do you help the work of these organisations?

We provide groups with a lot of hands on support – this could be working with trustees and senior staff to review governance procedures for example, or renewing an organisation’s business plan and identifying new activities or products they could explore. We also support organisations to think about how they capture and report on their impact, and help organisations that are looking to take on an asset from a local authority to run this for the benefit of the community. The peer support available through the Locality membership is of incredible benefit to organisations as it offers the opportunity to speak to others who have already been through an experience they are working through (redevelopment of a building for example) and we facilitate that through a number of networking events and an annual convention. We also seek to raise the profile of our members at a national level through our policy work and influence policymakers to create a more supportive policy and funding environment.

What tendencies do you see emerging among community organisations?

There has been an incredible response from communities in the UK in recent years as public services and assets have been threatened. Whilst closure of local libraries and swimming centres is very polemical, many community groups have fought hard to maintain services with new models of community ownership and management to ensure that these services are still available to the local community. Community organisations have also had to diversify their income models considerably in recent years as more traditional forms of grant funding have become less available.

How does self-organisation contribute to new ownership models of community facilities?

In a time of public sector austerity, privatisation of public assets and challenging trading for some local private sector facilities like shops and pubs, community shares have provided a mechanism to maintain common spaces with broad community ownership operating for the common good. This form of crowdfunding signals a new way in which communities are self-organising to maintain local facilities and services. Since 2009, almost 120,000 people have invested over £100m to support over 350 community businesses throughout the UK.

Community shares have been used to save a growing number of pubs and shops from closure where the private sector has retreated and residents fear the loss of local community assets, mobilising people to ‘save’ them through community share offers. They have also been used where the public sector has retreated and abandoned common spaces, formally in public ownership, such as Stretford Public Hall in Greater Manchester.

Other uses for new start-ups have been with the establishment of a new football club and community sport facilities by FC United (£2m+), providing affordable homes in Leeds through Leeds Community Homes (£360k+), piers and harbours such as pioneering Hastings Pier (£600k) and Portpatrick Harbour and even a whisky distillery raising over £2.5m (a very patient investment given the ageing process of whisky).

Community shares sit within a legal framework that requires the use of a specific business structure that enables one vote regardless of the level of investment, and enables withdrawable shares rather than tradable ‘transferable’ shares that are open to speculation. Community shares retain their original value, sometimes accruing small levels of interest. As the organisation matures they will usually allow a certain percentage of investors to withdraw shares, and may attract new shareholders in the process through an open offer. Shareholders become part of the organisation’s community and contribute towards a competitive advantage. Investors often invest financially as well as psychologically, becoming long term supporters, customers and users of the community business, with a genuine stake in its long term success.

Can you give an example for the use of community shares?

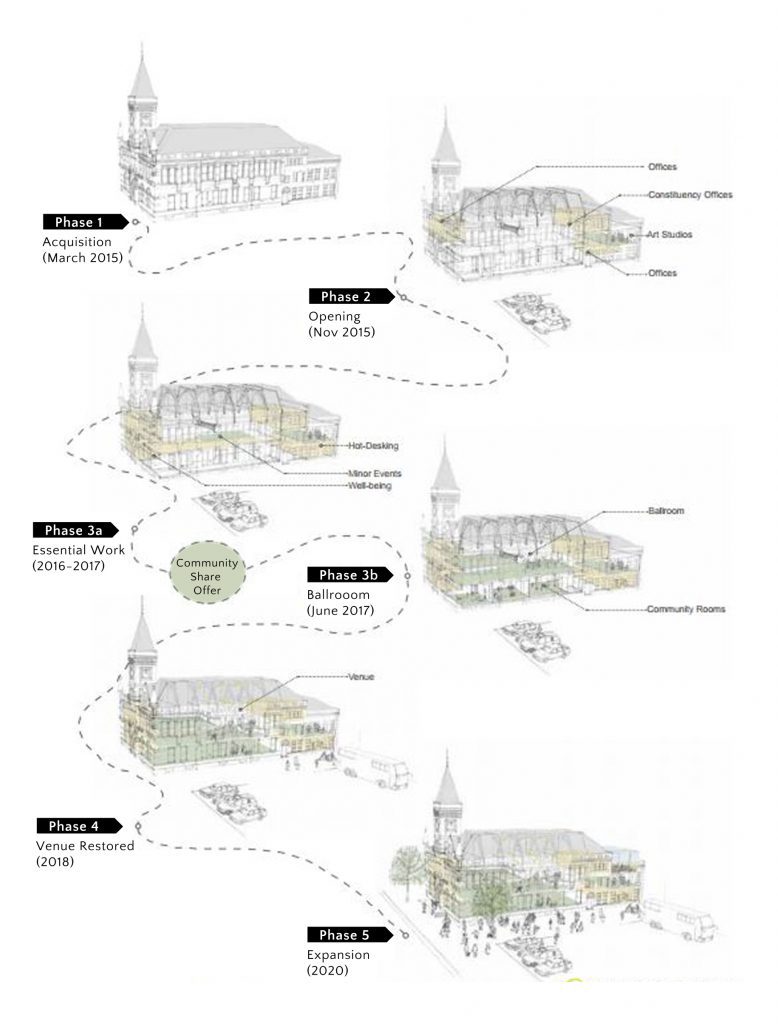

Stretford Public Hall is a great example. It is a beautiful Grade II listed building that has played a highly significant role in civic life in Stretford, Greater Manchester. Yet in 2013, its future came under threat with its proposed disposal by Trafford Council. It was at this time that the local community came together to save the Hall and bring it into community use. Following feasibility work, petitions, registering the building as an Asset of Community Value and ongoing community support, a group of community members were able to establish themselves as a Charitable Community Benefit Society and to secure an asset transfer of the building from the council into community ownership.

Following some minor repairs, the group started using some of the building. It was apparent they had a potentially large local audience interested in the building and the society, as well as a need for major capital investment to create a sustainable business model. The organisation had already established some trading activities, including artist studios, office space, co-working space and sessional space hire. The business model required maximising the use of all the space available. The investment would modernise the ballroom space and enabled enhanced usage to improve the overall income generating potential for the organisation.

Working with Locality, they wrote a more detailed business plan and share offer document and launched their share offer in early 2017. The minimum investment was £100, with the option of paying via 4 monthly instalments (chosen by 29%). They received 800 investments, including £130k of ‘institutional’ investments – organisations making significant investments. Of the nearly 800 community investors, the average investment was £160, with 87% coming from nearby postcodes. A well run and professional campaign, including a share offer launch party and press coverage created strong local momentum and enthusiasm in the project. They also received investments from across the country. The Friends of Stretford Public Hall Ltd successfully completed a community share offer in March 2017, raising over £250,000 to refurbish the ballroom.

What kind of commitment do community shares entail?

Buying community shares is a risk, so investors need to read the paperwork carefully and be aware of what they are buying and that they are satisfied with the business model. Usually, share offers will restrict withdrawals for the first few years, and only enable them once the business starts generating sufficient surpluses, so they need to be viewed as long term investments. You really do need to believe in the project. If you are buying community shares in a local community pub, shop or other community endeavour, it is logical that you would then support the business by being a customer or through other means such as voting at the AGM or even standing to become a trustee. This will help ‘crowd in’ sufficient people to make it successful. Some share offers offer small rates of interest on the initial investment, but they really need to be viewed as a social investment as much as a financial investment.

What happens to the money if the project folds?

One could lose one’s money, just as with any other share, that is why in any share offer there should be a very detailed business plan and people are advised to read it. If you run a good community share offer, you should be very clear about the fact that even if one can get their money out, it should be seen as a risk based long term investment.

Locality is a partner in the Community Shares Unit, which has sought to standardise and professionalise community share offers so they meet a minimum of good practice requirements. Share offers that meet this threshold can acquire the Community Shares Standard Mark, giving a level of investor confidence that the share offer has been externally reviewed.

Do community shares complement other funding sources for community projects?

Community shares are not a direct replacement for all grant funding, as there needs to be a solid business proposition underpinning the offer to enable long term share holder liquidity. However community shares are a really appealing mechanism for other funders, investors and government. They evidence local demand for a project and lower risk in the sense that there is a community of investors who have a long-term interest in the project’s success.

Often, community shares will be matched with other grant funding or social investment to form a cocktail of overall investment. Where organisations offer to pay interest to investors, this will usually be a modest amount, and indeed is restricted by legislation to what is reasonable. However, in many cases, the rate of interest may well be less than high street banks or specialist social investment bodies would offer. We are starting to see institutional investment, where social investment bodies will offer to invest a lump sum into a community share offer if that can be matched by the community. This gives the project a head start, being able to tell their community that they already have the backing of other investors. The Community Shares Booster Programme has pioneered this in the last few years.

What is the interest of a government to put its properties into community ownership?

The number of community asset transfers, where local community based organisations bid to take over a local authority building or facility has increased rapidly in the last few years. This is partly because the number of assets that are potentially available to communities has increased as local authorities have sought to consolidate their property portfolio and increase efficiencies. It has also emerged, sadly, because of the closure of some facilities that the local authority can no longer afford to run as a result of cuts in central government funding. However, government is also very aware of the additional value that a community organisation can bring to these assets, with groups raising large amounts of finance to renovate facilities and develop assets as centres offering new services to the community, and generating greater social value.

One powerful example of the value the community can bring when they take over the running of local assets is that of Bramley Baths in Leeds, the only remaining Edwardian bathhouse in Leeds and a Grade II listed building. In March 2011, Leeds City Council announced that they were planning to reduce the opening hours at Bramley Baths to 29 hours a week, and on weekdays the pool would only be open from 4pm-8pm, which would exclude local schools who regularly use the facilities. The council took this decision after being hit with £50 million of government cuts and £40 million of other budgetary pressures.

Local people reacted with concern and anger, fearing that their much loved local baths would be closed and lost. A community campaign to keep the baths open gained pace and received the support of the local MP, Rachel Reeves. In June 2011, Leeds City Council decided to invite expressions of interest to take over management of Bramley Baths. A group of residents and supportive local organisations worked together to write a business plan, raise funds and transfer Bramley Baths to the community. Bramley Baths became a not-for-profit, community-led, professionally run enterprise and began a new era on 1st January 2013.

Since 2013 a professional staff team backed by many supporters and volunteers, have turned around the fortunes of this much-loved community space. In addition to preserving a historic asset and providing a centre for fitness, fun and wellbeing, the community-led enterprise has also developed a number of new social activities, developing Bramley Baths as a social hub for the benefit of the community. The pool now runs at a profit and the community benefits in a number of new ways. Because the Baths are run by the community, for the community, this treasured local asset now meets local need more effectively and efficiently. A real learning point and achievement with Bramley Baths was that the asset was transferred without any closure of services. This meant that the building was not closed and left to deteriorate, causing additional cost and the need to re-establish a business model on re-opening.

Interview with Elly Townsend on 20 July 2017