Goteo is a platform for civic crowdfunding founded by Platoniq, a Catalan association of culture producers and software developers. Goteo helps citizen initiatives as well as social, cultural and technological projects that produce open source results and community benefits, with crowdfunding and crowdsourcing resources. Since its launch in 2011, Goteo’s crowdfunding campaigns have mobilised more than 90,000 people, collecting over 4,5 million euros and successfully funding initiatives in more than 70% of the cases. Beyond collecting funds, Goteo also helps initiatives gather non-monetary contributions and establish partnerships that can advance their work. Through the projects it enables, Goteo promotes transparency, open source information, knowledge exchange and cooperation among citizen initiatives and public authorities.

“The more open your project becomes, the more people it attracts and the bigger it grows”

Goteo is a complex entity, how would you describe yourselves?

Goteo is a collective that tries to promote participation and collaboration between institutions and citizens. With the Goteo platform, we help create stories through tools, merge them together and grow them; on the other hand, we also generate communities around initiatives. We work on bringing together individuals and public institutions to “collaborate forward,” for example, by opening up the institutional processes of participation or distributing funding evenly and in a more participatory way. We also track different organisational and development systems, including new funding models. More precisely, Goteo is a platform for crowdfunding campaigns, but it is not limited to funding: it also involves crowdsourcing. We do not only help our partners in acquiring the funds to carry a project on, but also in collecting non-economic contributions that a community can help with, and in sharing open-sourced collective benefits for the community, allowing projects to be replicated, reused, disseminated, or even improved or copied for further uses.

What makes the platform specific?

What is unique about Goteo is that we push for open source resources, collective initiatives, and we promote sharing collective benefits after a project passes through our crowdfunding campaign. We ask campaign promoters to publish their digital resources in an open source way once the campaign is over. It means sharing open source licenses, whether it’s a code or a design, a manual or any kind of file that shows the project. It is important for us to think of how this process contributes to the city and to the urban movement of gathering collective resources: we believe that it is an interesting way of putting clusters in movement.

Why so much emphasis on open-source?

We think that when you ask for support from a community, you should give something back. If you are an artist asking for funding for a CD, you should publish your CD with a creative common license or other free licenses afterwards, and give it back to the community. By doing so, we are also helping expand knowledge and provide access to free knowledge at a time when many forces are trying to enclose knowledge. The pressure on knowledge is similar to the pressure on social centres that are trying to resist enclosure.

Isn’t open source a constraint for the projects that run campaigns on your platform?

We really trust that the more open your project becomes, the more it attracts, the more it creates and the bigger it grows. That’s why we always push for the open licensing of the products and projects we support, and their outcomes – and that’s also why our platform itself is open source. You can download and copy the code of our platform, and have your own crowdfunding platform, use it, share it, improve it. We call this crowdfunding with crowd impact and crowd benefits. Goteo in Spanish means “leak”, and that’s how a campaign grows successful, drop by drop. Like the way you irrigate a garden: we understand that a way of funding collectively means that every drop adds to whatever you need to complete the watering of your garden.

How do the events you organise connect to the crowdfunding activities?

We believe that open knowledge creates more open knowledge, this is why we conduct workshops and bring together communities to cross-feed each other. Over 2000 people have come to our workshops, from many different countries and contexts: some apply the new ideas they gathered to urbanism, some to culture management, others to technology as well as many other fields. When you add layers to a project or invite different ideas to engage in dialogue with their counterparts, you can grow together and create more successful projects.

How do you define crowd benefits?

We always ask if crowdfunding is compatible with crowd benefits. People who prepare crowdfunding campaigns, ask us, “Do you think this is viable, do you think this feasible, do you think I can go through with it or is it something that is not going to be successful?” When we assess the project, we look for two ways of rewarding, not only the individuals who support the project, but also the community.

We divide rewards into two different groups: one consists of individual rewards, referring to when a person supports the project with 20 euros, and receives a postcard, a copy of your disk or participation in your workshop. The other refers to collective incentives that are more important for us, to push the community to support a project and add social importance to it. When something feels important and adds value to society, it is likely that more people will support and engage with it.

When we consider a project, we always ask promoters about their own experience, details, facts and issues of their projects that can help them conduct their projects in a better way. We ask about their needs. Of course, all projects in the fields of culture, urbanism and architecture need money. If there are no financial resources available, we look for alternative ways to support the project. We also ask about the tasks to be carried out, the infrastructures that they own, can count on or need and an outline of the materials needed for the project. Based on these, we assess what rewards one is able to give back to the community. Collective benefits can be digital archives, manual guides, codes, apps, websites or designs that can be downloaded, copied and adapted to the needs.

How can you help projects?

When gathering a group of people around a project, some might donate money while others might have important contributions that are not of a monetary nature. We promote our partners to also share their non-monetary needs in their communities. Projects often need a van to move things, or a translation. We have a feature on our platform to exchange these possible means of cooperation. We feel that when people get together and get to know each other and their projects, it is also easier to engage them and create community through social networks.

On average, around 200 people support each project, with contributions that range from 20 euros to 1500 or with their skills. 70% of our crowdfunding campaigns are successful, and one of every three donors does not want anything in return, they are donating because they value the project. We believe it is possible to talk about the culture of generosity in a world where we are constantly told that we have to be individuals, and we have to make it ourselves, be self-made men. We believe instead that the culture of generosity is really at our core, in our heart.

How do you define how much money is obtainable with a crowdfunding campaign?

We always establish two different budget goals for campaigns: there is a minimum which we consider the project needs just to kickstart, and then there is an optimum budget that could take the project further. We do respect the numbers identified by the promoters themselves, because they know more than anyone else about their needs and the costs in their local contexts, but we keep an eye on budget requests to make sure that what they ask for is clear and the plan is coherent. We suggest to keep the projected budgets at the right scale and advise initiators to make their budgets transparent and modular: if a project needs 10.000 euros, what budget categories does it include? Once initiators understand their own budget better, they often realise that some their needs can be covered with existing infrastructure or non-monetary contributions. Another criteria for projecting budget is an initiative’s capacity of social outreach: if an organisation has never disseminated anything in social media, or the initiator is an individual with limited online engagement, it might be better to keep the projected budget low. To this, we add another specific layer of knowledge about what different people from random places can do in areas that are not necessarily on our minds, for instance, in rural areas. We are generally very much focused on cities, but there are interesting initiatives in rural areas that contribute to the commons.

What is your experience about campaigns that addressed development or construction projects?

We had several campaigns in the fields of urbanism and architecture: they give us insights on how to facilitate different behaviours in urban and rural areas and how to share knowledge among communities that were previously not in touch. For instance, La Fabrika de Toda la Vida is an initiative using a former cement factory in Estremadura, not far from the Portuguese border: they financed their start-up phase, the rebuilding of a part of an enormous factory, with a successful crowdfunding campaign through Goteo, they raised 133% of their minimum budget. Their offer to give back to society was the building itself: they turned it into an open space that anyone can use and suggest activities for.

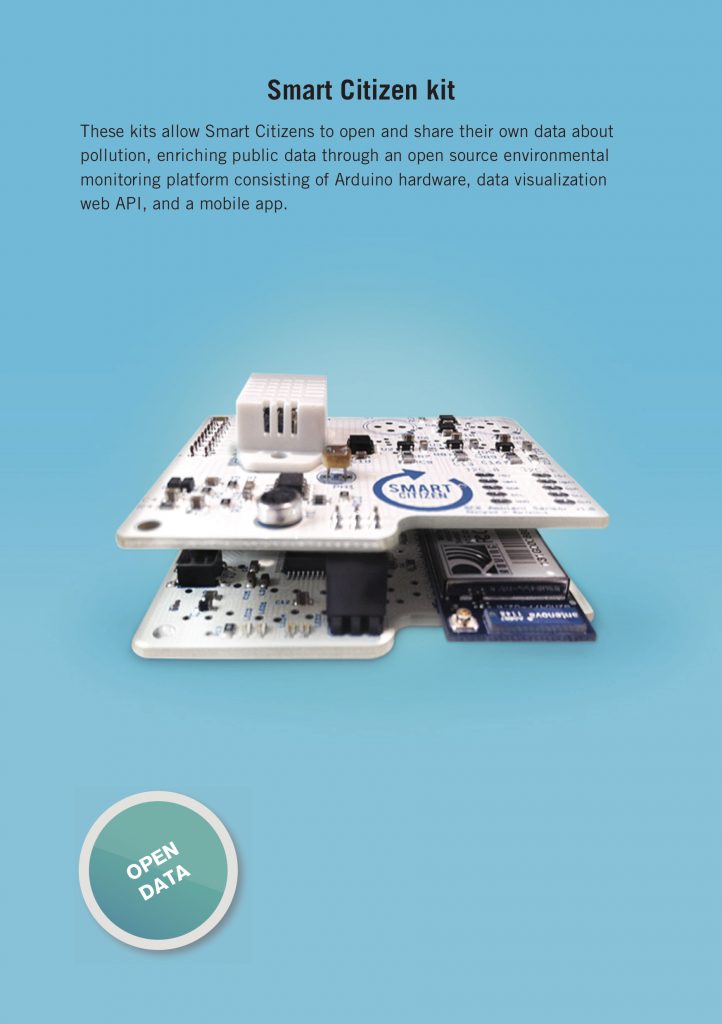

Another example is the Instituto Do It Yourself: it is a knowledge hub, an infrastructure that helps people exchange knowledge in a peripheral neighbourhood of Madrid. The Institute was started in 2013; it is a nice example of a free knowledge resource, established with the help of a campaign we launched together. There are also journalism projects we supported that are closely linked with urbanism. For instance, Goteo supported a campaign for a research on land use in Galicia, Northern Spain, where wildfires are closely connected to speculation: the devastation caused by wildfires usually opens the way for changing land use and building more profitable buildings on formerly agricultural land. Another project is the Smart Citizen Kit, built with open-source Arduino hardware to be installed in your home. The kit monitors air quality and sends data to a centralised device that collects data from different parts of a city.

How do your campaigns contribute to the creation of a more collaborative tissue of community initiatives?

Processes through our platform turn out to be barometers of what a more collaborative and ethical society could become through implementing more open source collaborative processes and programs. For instance, some projects deal with cooperation in a larger sense. One of the initiatives produced a set of coins, kind of tokens, for collectives, companies of big groups to measure their collaborations: a way to visualise a chain of favours, to highlight how non-monetary contributions and collaborations function within a team or among several teams.

What are the overall results of the platform?

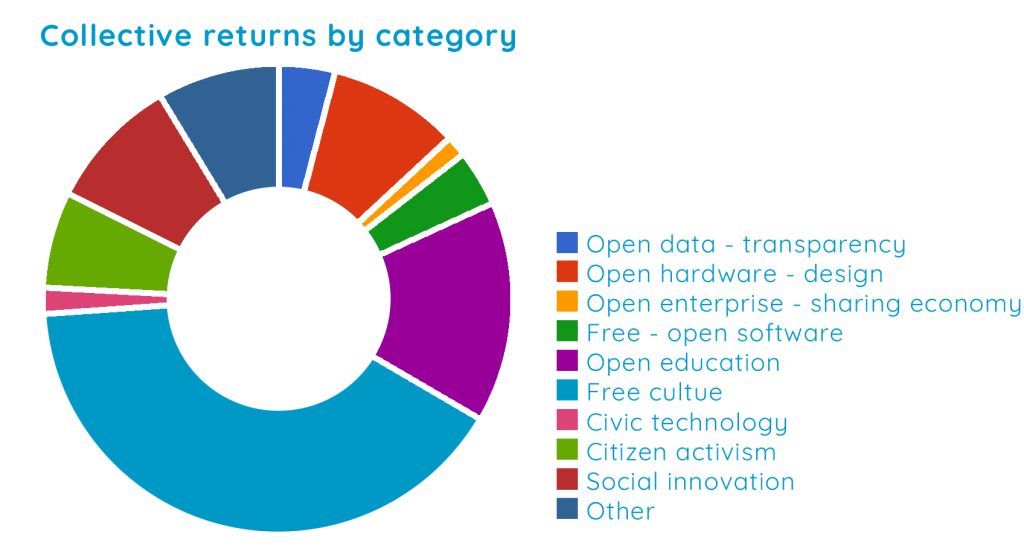

In five years, we collected over 4,5 million euros altogether, with an average contribution of 48 euros, and with over 200,000 euros in match funding. At stats.goteo.org, the platform has open data about our campaigns: it shows tendencies, categories, money collected for each project, and the time it takes a project to collect the necessary funding. We also developed an app with which people can freely use the data. Tracking accountability is very important for us: the more we know about a project we support, the more vigilant we can be in what they do, and also receive better outcomes from them.

Do public institutions play any role in your campaigns?

It is an important issue. Some people would say, “All right, crowdfunding is nice, and so are the collective benefits, but we are exploiting our families, our friends, communities and ourselves just to extract more money from them for our projects. Isn’t it a bit contradictory, doesn’t it promote the notion of ‘Big Society’ advocated by conservative ideologues?” We’re aware of this and work on attracting private and public money, to balance contributions to the projects we support: we work on many of our funding processes with private companies as well as with different local and regional public administrations and universities.

In the past years, we have been working with various public administrations, and they would agree to add some budget to specific calls, match funding a set of campaigns selected by an open panel including public officials and our team with 10,000 or 12,000 euros. These are projects that go through crowdfunding campaigns, but public institutions double the amount given by citizens; so for each euro made through crowdfunding, the administration offers another euro. It is a way to open the process of decision-making: there are initiatives that institutions would not fund without collective support.

La Fabrika de Toda la Vida for instance, was also supported by the regional government’s match funding. At the time, the conservative government of the Estremadura region would probably have not understood what it meant to restore a former factory in a village; but with the support shown to the project by other institutions, the citizens and us, they realised that it was intelligent to invest in a project like this.

Our cooperation with public institutions is not exclusively monetary. Lately we have been working with public institutions, for instance with different municipalities in Barcelona and elsewhere, on how they are developing their participatory processes, their policy-making, and on how they can engage their citizens and promote more open and meaningful decision-making processes. This is a horizon that we have: we are looking for growing alliances between public and private actors to raise funding for citizen projects, soon at a much larger scale than today.

This text in an excerpt from the book Funding the Cooperative City: Community finance and the economy of civic spaces.

Interview with Carmen Lozano Bright, Goteo

21 April 2016